Chinese Furniture: Probable source of artistic taste—Sir William Chambers quoted— Raeinet’s "be Costume Historique"—Dutch influence—The South Kensington and the Duke of Edinburgh Collections—Processes of making bacquer—Screens in the Kensington Museum. Japanese Furniture: Early History—Sir Rutherford Alcock and bord Elgin—The Collection of the Shogun—Famous Collections—Action of the present Government of Japan—Special characteristics. Indian Furniture: Early European influence—Furniture of the Moguls—Racinet’s Work—Bombay Furniture—Ivory Chairs and Table—Specimens in the India Museum. Persian Woodwork: Collection of Objets dArt formed by General Murdoch Smith, R. E.—Industrial Arts of the Persians—Arab influence—South Kensington Specimens. Saracenic Woodwork: Oriental customs—Specimens in the South Kensington Museum of Arab Work—M. dAveune’s Work.

e have been unable to discover when the Chinese first began to use State or domestic furniture. Whether, like the ancient Assyrians and Egyptians, there was an early civilization which included the arts of joining, carving, and upholstering, we do not know; most probably there was; and from the plaster casts which one sees in our Indian Museum, of the ornamental stone gateways of Sanchi Tope, Bhopal in Central India, it would appear that in the early part of our Christian era, the carvings in wood of their neighbours and co-religionists, the Hindoos, represented figures of men and animals in the woodwork of sacred buildings or palaces; and the marvellous dexterity in manipulating wood, ivory and stone which we recognize in the Chinese of today, is inherited from their ancestors.

e have been unable to discover when the Chinese first began to use State or domestic furniture. Whether, like the ancient Assyrians and Egyptians, there was an early civilization which included the arts of joining, carving, and upholstering, we do not know; most probably there was; and from the plaster casts which one sees in our Indian Museum, of the ornamental stone gateways of Sanchi Tope, Bhopal in Central India, it would appear that in the early part of our Christian era, the carvings in wood of their neighbours and co-religionists, the Hindoos, represented figures of men and animals in the woodwork of sacred buildings or palaces; and the marvellous dexterity in manipulating wood, ivory and stone which we recognize in the Chinese of today, is inherited from their ancestors.

Sir William Chambers travelled in China in the early part of the last century. It was he who introduced "the Chinese style" into furniture and decoration, which was adopted by Chippendale and other makers, as will be noticed in the chapter dealing with that period of English furniture. He gives us the following description of the furniture he found in "The Flowery Land."

"The moveables of the saloon consist of chairs, stools, and tables; made sometimes of rosewood, ebony, or lacquered work, and sometimes of bamboo only, which is cheap, and, nevertheless, very neat. When the moveables are of wood, the seats of the stools are often of marble or porcelain, which, though hard to sit on, are far from unpleasant in a climate where the summer heats are so excessive. In the corners of the rooms are stands four or live feet high, on which they set plates of citrons, and other fragrant fruits, or branches of coral in vases of porcelain, and glass globes containing goldfish, together with a certain weed somewhat resembling fennel; on such tables as are intended for ornament only they also place little landscapes, composed of rocks, shrubs, and a kind of lily that grows among pebbles covered with water. Sometimes also, they have artificial landscapes made of ivory, crystal, amber, pearls, and various stones. I have seen some of these that cost over 300 guineas, but they are at best mere baubles, and miserable imitations of nature. Besides these landscapes they adorn their tables with several vases of porcelain, and little vases of copper, which are held in great esteem. These are generally of simple and pleasing forms. The Chinese say they were made two thousand years ago, by some of their celebrated artists, and such as are real antiques (for there are many counterfeits) they buy at an extravagant price, giving sometimes no less than £300 sterling for one of them.

"The bedroom is divided from the saloon by a partition of folding doors, which, when the weather is hot, are in the night thrown open to admit the air. It is very small, and contains no other furniture than the bed, and some varnished chests in which they keep their apparel. The beds are very magnificent; the bedsteads are made much like ours in Europe—of rosewood, carved, or lacquered work: the curtains are of taffeta or gauze, sometimes flowered with gold, and commonly either blue or purple. About the top a slip of white satin, a foot in breadth, runs all round, on which are painted, in panels, different figures—flower pieces, landscapes, and conversation pieces, interspersed with moral sentences and fables written in Indian ink and vermilion."

From old paintings and engravings which date from about the fourteenth or fifteenth century one gathers an idea of such furniture as existed in China and Japan in earlier times. In one of these, which is reproduced in Racinet’s "Le Costume Historique," there is a Chinese princess reclining on a sofa which has a frame of black wood visible, and slightly ornamented; it is upholstered with rich embroidery, for which these artistic people seem to have been famous from a very early period. A servant stands by her side to hand her the pipe of opium with which the monotony of the day was varied—one arm rests on a small wooden table or stand which is placed on the sofa, and which holds a flower vase and a pipe stand.

On another old painting two figures are seated on mats playing a game which resembles draughts, the pieces being moved about on a little table with black and white squares like a modern chessboard, with shaped feet to raise it a convenient height for the players: on the floor stand cups of tea ready to hand. Such pictures are generally ascribed to the fifteenth century, the period of the great Ming dynasty, which appears to have been the time of an improved culture and taste in China.

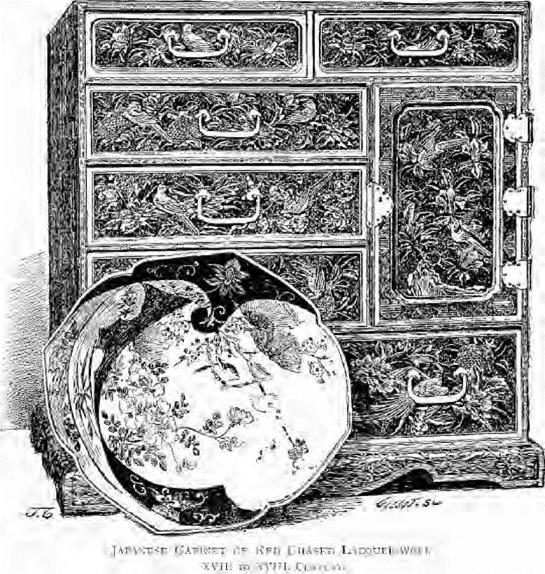

From this time and a century later (the sixteenth) also date those beautiful cabinets of lacquered wood enriched with ivory, mother of pearl, with silver and even with gold, which have been brought to England occasionally; but genuine specimens of this, and of the seventeenth century, are very scarce and extremely valuable.

The older Chinese furniture which one sees generally in Europe dates from the eighteenth century, and was made to order and imported by the Dutch; this explains the curious combination to be found of Oriental and European designs; thus, there are screens with views of Amsterdam and other cities copied from paintings sent out for the purpose, while the frames of the panels are of carved rosewood of the fretted bamboo pattern characteristic of the Chinese. Elaborate bedsteads, tables and cabinets were also made, with panels of ash stained a dark color and ornamented with hunting scenes, in which the men and horses are of ivory, or sometimes with ivory faces and limbs, the clothes being chiefly in a brown colored wood.

In a beautiful table in the South Kensington Museum, which is said to have been made in Cochin-China, mother of pearl is largely used and produces a rich effect.

The furniture brought back by the Duke of Edinburgh from China and Japan is of the usual character imported, and the remarks hereafter made on Indian or Bombay furniture apply equally to this adaptation of Chinese detail to European designs.

The most highly prized work of China and Japan in the way of decorative furniture is the beautiful lacquer work, and in the notice on French furniture of the eighteenth century, in a subsequent chapter, we shall see that the process was adopted in Holland, France and England with more or less success.

It is worth while, however, to allude to it here a little more fully.

The process as practised in China is thus described by M. Jacquemart:—

"The wood when smoothly planed is covered with a sheet of thin paper or silk gauze, over which is spread a thick coating made of powdered red sandstone and buffalo’s gall. This is allowed to dry, after which it is polished and rubbed with wax, or else receives a wash of gum water, holding chalk in solution. The varnish is laid on with a flat brush, and the article is placed in a damp drying room, whence it passes into the hands of a workman, who moistens and again polishes it with a piece of very fine grained soft clay slate, or with the stalks of the horse-tail or shave grass. It then receives a second coating of lacquer, and when dry is once more polished. These operations are repeated until the surface becomes perfectly smooth and lustrous. There are never applied less than three coatings and seldom more than eighteen, though some old Chinese and some Japan ware are said to have received upwards of twenty. As regards China, this seems quite exceptional, for there is in the Louvre a piece with the legend ‘lou-tinsg,’ i. e. six coatings, implying that even so many are unusual enough to be worthy of special mention."

There is as much difference between different kinds and qualities of lac as between different classes of marquctcrie.

The most highly prized is the LACQUER ON GOLD GROUND, and the specimens of this which first reached Europe during the time of Louis XV., were presentation pieces from the Japanese Princes to some of the Dutch officials.

Gold ground lacquer is rarely found in furniture, and only as a rule in some of those charming little boxes, in which the luminous effect of the lac is heightened by the introduction of silver foliage on a minute scale, or of tiny landscape work and figures charmingly treated, partly with dull gold and partly highly burnished. Small placques of this beautiful ware were used for some of the choicest pieces of Gouthiere’s elegant furniture made for Marie Antoinette.

Aventurine lacquer closely imitates in color the sparkling mineral from which it takes its name, and a less highly finished preparation is used as a lining for the small drawers of cabinets. Another lacquer has a black ground, on which landscapes delicately traced in gold stand out in charming relief. Such pieces were used by Riesener and mounted by Gouthiere in some of the most costly furniture made for Marie Antoinette; some specimens are in the Louvre. It is this kind of lacquer, in varying qualities, that is usually found in cabinets, folding screens, coffers, tables, etageres, and other ornamental articles of furniture. Enriched with inlay of mother of pearl, the effect of which is in some cases heightened and rendered more effective by some transparent coloring on its reverse side, as in the case of a bird’s plumage or of those beautiful blossoms which both Chinese and Japanese artists can represent so faithfully.

A very remarkable screen in Chinese lacquer of later date is in the South Kensington Museum; it is composed of twelve folds each ten feet high, and measuring when fully extended twenty-one feet. This screen is very beautifully decorated on both sides with incised and raised ornaments painted and gilt on black ground, with a rich border ornamented with representations of sacred symbols and various other objects. The price paid for it was £1,000. There are also in the Museum some very rich chairs of modern Chinese work, in brown wood, probably teak, very elaborately inlaid with mother-of-pearl; they were exhibited in Paris in 1867.

Of the very early history of Japanese industrial arts we know but little. We have no record of the kind of furniture which Marco Polo found when he travelled in Japan in the thirteenth century, and until the Jesuit missionaries obtained a footing in the sixteenth century and sent home specimens of native work, there was probably very little of Japanese manufacture which found its way to Europe. The beautiful lacquer work of Japan, which dates from the end of the sixteenth and the following century, leads us to suppose that a long period of probation must have occurred before the Arts, which were probably learned from the Chinese, could have been so thoroughly mastered.

Of furniture, with the exception of the cabinets, chests, and boxes, large and small, of this famous lac, there appears to have been little. Until the Japanese developed a taste for copying European customs and manners, the habit seems to have been to sit on mats and to use small tables raised a few inches from the ground. Even the bedrooms contained no bedsteads, but a light mattress served for bed and bedstead.

The process of lacquering has already been described, and in the chapter on French furniture of the eighteenth century it will be seen how specimens of this decorative material reached France by way of Holland, and were mounted into the "meubles de luxe" of that time. With this exception, and that of the famous collection of porcelain in the Japan Palace at Dresden, probably but little of the art products of this artistic people had been exported until the country was opened up by the expedition of Lord Elgin and Commodore Perry, in 1858-9, and subsequently by the antiquarian knowledge and research of Sir Rutherford Alcock, who has contributed so much to our knowledge of Japanese industrial art; indeed it is scarcely too much to say, that so far as England is concerned, he was the first to introduce the products of the Empire of Japan.

The Revolution, and the break up of the feudal system which had existed in that country for some eight hundred years, ended by placing the Mikado on the throne. There was a sale in Paris, in 1867, of the famous collection of the Shogun, who had sent his treasures there to raise funds for the civil war in which he was then engaged with the Daimio. This was followed by the exportation of other fine native productions to Paris and London; but the supply of old and really fine specimens has, since about 1874, almost ceased, and, in default, the European markets have become flooded with articles of cheap and inferior workmanship, exported to meet the modern demand. The present Government of Japan, anxious to recover many of the masterpieces which were produced in the best time, under the patronage of the native princes of the old regime, have established a museum at Tokio, where many examples of fine lacquer work, which had been sent to Europe for sale, have been placed after repurchase, to serve as examples for native artists to copy, and to assist in the restoration of the ancient reputation of Japan.

|

|

There is in the South Kensington Museum a very beautiful Japanese chest of lacquer work made about the beginning of the seventeenth century, the best time for Japanese art; it formerly belonged to Napoleon I. and was purchased at the Hamilton Palace Sale for £722: it is some 3 ft. 3 in. long and 2 ft. 1 in. high, and was intended originally as a receptacle for sacred Buddhist books. There are, most delicately worked on to its surface, views of the interior of one of the Imperial Palaces of Japan, and a hunting scene. Mother-of-pearl, gold, silver, and aventurine, are all used in the enrichment of this beautiful specimen of inlaid work, and the lock plate is a representative example of the best kind of metal work as applied to this purpose.

H. R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh has several fine specimens of Chinese and Japanese lacquer work in his collection, about the arrangement of which the writer had the honour of advising his Royal Highness, when it arrived some years ago at Clarence House. The earliest specimen is a reading desk, presented by the Mikado, with a slope for a book much resembling an ordinary bookrest, but charmingly decorated with lacquer in landscape subjects on the flat surfaces, while the smaller parts are diapered with flowers and quatrefoils in relief of lac and gold. This is of the sixteenth century. The collections of the Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, Sir Rutherford Alcock, K. C.B., Mr. Salting, Viscount Gough, and other well-known amateurs, contain some excellent examples of the best periods of Japanese Art work of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The grotesque carving of the wonderful dragons and marvellous monsters introduced into furniture made by the Chinese and Japanese, and especially in the ornamental woodwork of the Old Temples, is thoroughly peculiar to these masters of elaborate design and skilful manipulation: and the low rate of remuneration, compared with our European notions of wages, enables work to be produced that would be impracticable under any other conditions. In comparing the decorative work on Chinese and Japanese furniture, it may be said that more eccentricity is effected by the latter than by the former in their designs and general decorative work. The Japanese joiner is unsurpassed, and much of the lattice work, admirable in design and workmanship, is so quaint and intricate that only by close examination can it be distinguished from finely cut fret work.