England under Henry the Eighth was peaceful and prosperous, and the King was ambitious to outvie his French contemporary, Francois I., in the sumptuousness of his palaces. John of Padua, Holbein, Havernius of Cleves, and other artists, were induced to come to England and to introduce the new style. It, however, was of slow growth, and we have in the mixture of Gothic, Italian and Flemish ornament, the style which is known as "Tudor."

It has been well said that "Feudalism was ruined by gunpowder." The old-fashioned feudal castle was no longer proof against cannon, and with the new order of things, threatening walls and serried battlements gave way as if by magic to the pomp and grace of the Italian mansion. High roofed gables, rows of windows and glittering oriels looking down on terraced gardens, with vases and fountains, mark the new epoch.

|

CahVeji Oak Сі-іеВї r* ire Stvl? ‘jv Holkl’-jn. |

The joiner’s work played a very important part in the interior decoration of the castles and country seats of this time, and the roofs were magnificently timbered with native oak, which was available in longer lengths than that of foreign growth. The Great Hall in Hampton Court Palace, which was built by Cardinal Wolsey and presented to his master, the halls of Oxford, and many other public buildings which remain to us, are examples of fine woodwork in the roofs. Oak panelling was largely used to line the walls of the great halls, the "linen scroll pattern" being a favorite form of ornament. This term describes a panel carved to represent a napkin folded in close convolutions, and appears to have been adopted from German work; specimens of this can be seen at Hampton Court, and in old churches decorated in the early part of the sixteenth century. There is also some fine panelling of this date in King’s College, Cambridge.

In this class of work, which accompanied the style known in architecture as the "Perpendicular," some of the finest specimens of oak ornamented interiors are to be found, that of the roof and choir stalls in the beautiful Chapel of Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey, being world famous. The carved enrichments of the under part of the seats, or "misericords," are especially minute, the subjects apparently being taken from old German engravings. This work was done in England before architecture and wood carving had altogether flung aside their Gothic trammels, and shews an admixture of the new Italian style which was afterwards so generally adopted.

There are in the British Museum some interesting records of contracts made in the ninth year of Henry VIII.’s reign for joyner’s work at Hengrave, in which the making of ‘livery’ or service cupboards is specified.

"Ye cobards they be made ye facyon of livery y is w’thout doors."

These were fitted up by the ordinary house carpenters, and consisted of three stages or shelves standing on four turned legs, with a drawer for table linen. They were at this period not enclosed, but the mugs or drinking vessels were hung on hooks, and were taken down and replaced after use; a ewer and basin was also part of the complement of a livery cupboard, for cleansing these cups. In Harrison’s description of England in the latter part of the sixteenth century the custom is thus described:

"Each one as necessitie urgeth, calleth for a cup of such drinke as him liketh, so when he hath tasted it, he delivereth the cup again to some one of the standers by, who maketh it clean by pouring out the drinke that remaineth, restoreth it to the cupboard from whence he fetched the same."

It must be borne in mind, in considering the furniture of the earlier part of the sixteenth century, that the religious persecutions of the time, together with the general break-up of the feudal system, had gradually brought about the disuse of the old custom of the master of the house taking his meals in the large hall or "houseplace," together with his retainers and dependants; and a smaller room leading from the great hall was fitted up with a dressoir or service cupboard, for the drinking vessels in the manner just described, with a bedstead, and a chair, some benches, and the board on trestles, which formed the table of the period. This room, called a "parler" or "privee parloir," was the part of the house where the family enjoyed domestic life, and it is a singular fact that the Clerics of the time, and also the Court party, saw in this tendency towards private life so grave an objection that, in 1526, this change in fashion was the subject of a court ordinance, and also of a special Pastoral from Bishop Grosbeste. The text runs thus: "Sundrie noblemen and gentlemen and others doe much delighte to dyne in corners and secret places," and the reason given, was that it was a bad influence, dividing class from class; the real reason was probably that by more private and domestic life, the power of the Church over her members was weakened.

|

|

In spite, however, of opposition in high places, the custom of using the smaller rooms became more common, and we shall find the furniture, as time goes on, designed accordingly.

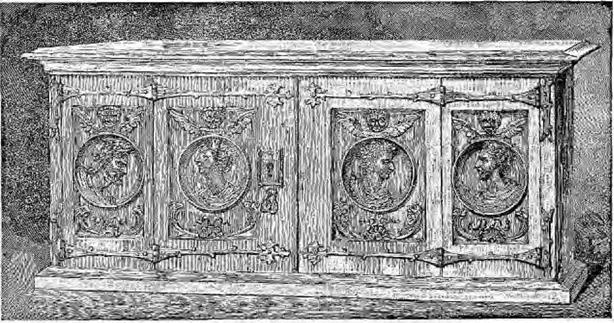

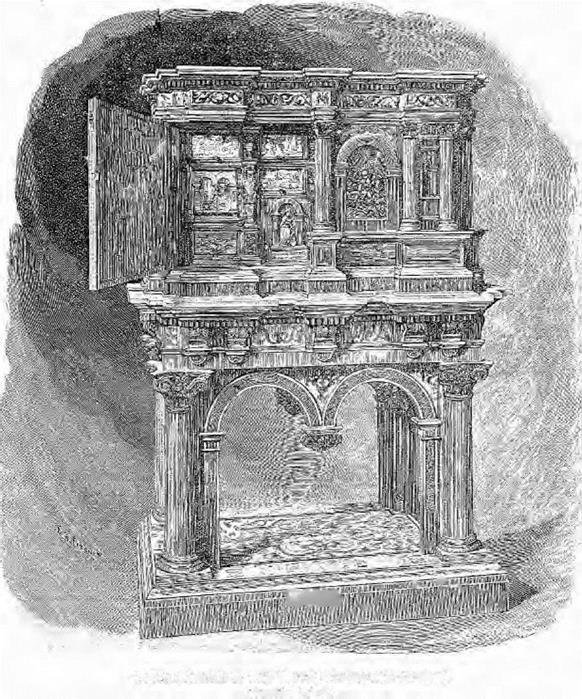

In the South Kensington Museum there is a very remarkable cabinet, the decoration of which points to its being made in England at this time, that is, about the middle, or during the latter half, of the sixteenth century, but the highly finished and intricate marqueterie and carving would seem to prove that Italian or German craftsmen had executed the work. It should be carefully examined as a very interesting specimen. The Tudor arms, the rose and portcullis, are inlaid on the stand. The arched panels in the folding doors, and at the ends of the cabinet are in high relief, representing battle scenes, and bear some resemblance to Holbein’s style. The general arrangement of the design reminds one of a Roman triumphal arch. The woods employed are chiefly pear tree, inlaid with coromandel and other woods. Its height is 4 ft. 7 in. and width 3 ft. 1 in., but there is in it an immense amount of careful detail which could only be the work of the most skilful

craftsmen of the day, and it was evidently intended for a room of moderate dimensions where the intricacies of design could be observed. Mr. Hungerford Pollen has described this cabinet fully, giving the subjects of the ornament, the Latin mottoes and inscriptions, and other details, which occupy over four closely printed pages of his museum catalogue. It cost the nation £500, and was an exceedingly judicious purchase.

craftsmen of the day, and it was evidently intended for a room of moderate dimensions where the intricacies of design could be observed. Mr. Hungerford Pollen has described this cabinet fully, giving the subjects of the ornament, the Latin mottoes and inscriptions, and other details, which occupy over four closely printed pages of his museum catalogue. It cost the nation £500, and was an exceedingly judicious purchase.

TППГТ – Сльшвф і* the Sol.’ih Кнчаенугон Мианта.

! EflECtltUftl bclos.)

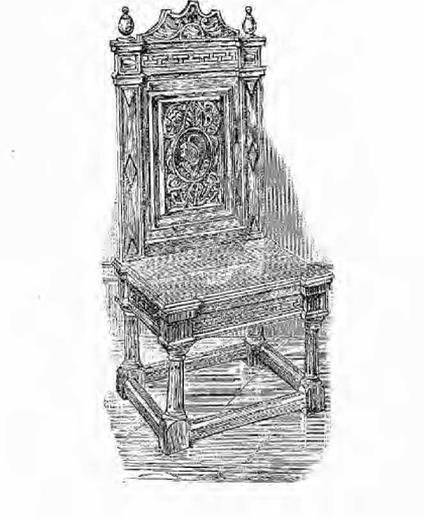

Chairs were during the first half of the sixteenth century very scarce articles, and as we have seen with other countries, only used for the master or mistress of the house. The chair which is said to have belonged to Anna Boleyn, of which an illustration is given on p. 74, is from the collection of the late Mr. Geo. Godwin, F. S.A., formerly editor of "The Builder," and was part of the contents of Hever Castle, in Kent. It is of carved oak, inlaid with ebony and boxwood, and was probably made by an Italian workman. Settles were largely used, and both these and such chairs as then existed, were dependent, for richness of effect, upon the loose cushions with which they were furnished.

If we attempt to gain a knowledge of the designs of the tables of the sixteenth, and early part of the seventeenth centuries, from interiors represented in paintings of this period, the visit to the picture gallery will be almost in vain, for in nearly every case the table is covered by a cloth. As these cloths or carpets, as they were then termed, to distinguish them from the "tapet" or floor covering, often cost far more than the articles they covered, a word about them may be allowed.

Most of the old inventories from 1590, after mentioning the "framed" or "joyned" table, name the "carpett of Turky werke" which covered it, and in many cases there was still another covering to protect the best one, and when Frederick, Duke of Wurtemburg, visited England in 1592 he noted a very extravagant "carpett" at Hampton Court, which was embroidered with pearls and cost 50,000 crowns.

The cushions or "quysshens" for the chairs, of embroidered velvet, were also very important appendages to the otherwise hard oaken and ebony seats, and as the actual date of the will of Alderman Glasseor quoted below is 1589, we may gather from the extract given, something of the character and value of these ornamental accessories which would probably have been in use for some five and twenty or thirty years previously.

"Inventory of the contents of the parler of St. Jone’s, within the cittie of Chester," of which place Alderman Glasseor was vice-chamberlain:—

"A drawinge table of joyned work with a frame," valued at "xl

shillings," equilius Labour £20 your present money.

Two formes covered with Turkey work to the same belonginge. xiij

shillings and iiij pence

A joyned frame xvjd.

A bord ijs. vjd.

A little side table upon a frame ijs. vd.

A pair of virginalls with the frame xxxs.

Sixe joyned stooles covr’d with nedle werke xvs.

Sixe other joyned stooles vjs.

One cheare of nedle worke iijs. iiijd.

Two little fote stooles iiijd.

One longe carpett of Turky werke vilz.

A shortte carpett of the same werke xiijs. iijd.

One cupbord carpett of the same xs.

Sixe quysshens of Turkye xijs.

Sixe quysshens of tapestree xxs.

And others of velvet "embroidered wt gold and silver armes in the middesle."

Eight pictures xls. Maps, a pedigree of Earl Leicester in "joyned frame" and a list of books.

This Alderman Glasseor was apparently a man of taste and culture for those days; he had "casting bottles" of silver for sprinkling perfumes after dinner, and he also had a country house "at the sea," where his parlour was furnished with "a canapy bedd."

As the century advances, and we get well into Elizabeth’s reign, wood carving becomes more ambitious, and although it is impossible to distinguish the work of Flemish carvers who had settled in England from that of our native craftsmen, these doubtless acquired from the former much of their skill. In the costumes and in the faces of figures or busts, produced in the highly ornamental oak chimney pieces of the time, or in the carved portions of the fourpost bedsteads, the national characteristics are preserved, and, with a certain grotesqueness introduced into the treatment of accessories, combine to distinguish the English school of Elizabethan ornament from other contemporary work.

Knole, Longleaf, Burleigh, Hatfield, Hardwick, and Audley End are familiar instances of the change in interior decoration which accompanied that in architecture; terminal figures, that is, pedestals diminishing towards their bases, surmounted by busts of men or women, elaborate interlaced strap work carved in low relief, trophies of fruit and flowers, take the places of the more Gothic treatment formerly in vogue. The change in the design of furniture naturally followed, for in cases where Flemish or Italian carvers were not employed, the actual execution was often by the hand of the house carpenter, who was influenced by what he saw around him.

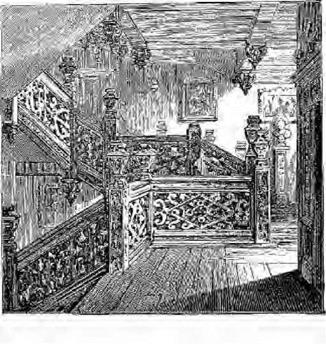

The great chimney piece in Speke Hall, near Liverpool, portions of the staircase of Hatfield, and of other English mansions before mentioned, are good examples of the wood carving of this period, and the illustrations from authenticated examples which are given, will assist the reader to follow these remarks.

|

|

There is a mirror frame at Goodrich Court of early Elizabethan work, carved in oak and partly gilt; the design is in the best style of Renaissance and more like Italian or French work than English. Architectural mouldings, wreaths of flowers, cupids, and an allegorical figure of Faith are harmoniously combined in the design, the size of the whole frame being 4 ft. 5 ins. by 3 ft. 6 ins. It bears the date 1559 and initials R. M.; this was the year in which Roland Meyrick became Bishop of Bangor, and it is still in the possession of the Meyrick family. A careful drawing of this frame was made by Henry Shaw, F. S.A., and published in "Specimens of Ancient Furniture drawn from existing Authorities," in 1836. This valuable work of reference also contains finished drawings of other noteworthy examples of the sixteenth century furniture and woodwork. Amongst these is one of the Abbot’s chair at Glastonbury, temp. Henry VIII., the original of the chair familiar to us now in the chancel of most churches; also a chair in the state-room of Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, covered with crimson velvet embroidered with silver tissue, and others, very interesting to refer to because the illustrations are all drawn from the articles themselves, and their descriptions are written by an excellent antiquarian and collector, Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick.

The mirror frame, described above, was probably one of the first of its size and kind in England. It was the custom, as has been already stated, to paint the walls with subjects from history or Scripture, and there are many precepts in existence from early times until about the beginning of Henry VIII.’s reign, directing how certain walls were to be decorated. The discontinuance of this fashion brought about the framing of pictures, and some of the paintings by Holbein, who came to this country about 1511, and received the patronage of Henry VIII. some fourteen or fifteen years later, are probably the first pictures that were framed in England. There are some two or three of these at Hampton Court Palace, the ornament being a scroll in gold on a black background, the width of the frame very small in comparison with its canvas. Some of the old wall paintings had been on a small scale, and, where long stories were represented, the subjects instead of occupying the whole flank of the wall, had been divided into rows some three feet or less in height, these being separated by battens, and therefore the first frames would appear to be really little more than the addition of vertical sides to the horizontal top and bottom which such battens had formed. Subsequently, frames became more ornate and elaborate. After their application to pictures, their use for mirrors was but a step in advance, and the mirror in a carved and gilt or decorated frame, probably at first imported and afterwards copied, came to replace the older mirror of very small dimensions for toilet use.

Until early in the fifteenth century, mirrors of polished steel in the antique style, framed in silver and ivory, had been used; in the wardrobe account of Edward I. the item occurs, "A comb and a mirror of silver gilt," and we have an extract from the privy purse of expenses of Henry VIII. which mentions the payment "to a Frenchman for certayne loking glasses," which would probably be a novelty then brought to his Majesty’s notice.

Indeed, there was no glass used for windows8 previous to the fifteenth century, the substitute being shaved horn, parchment, and sometimes mica, let into the shutters which enclosed the window opening.

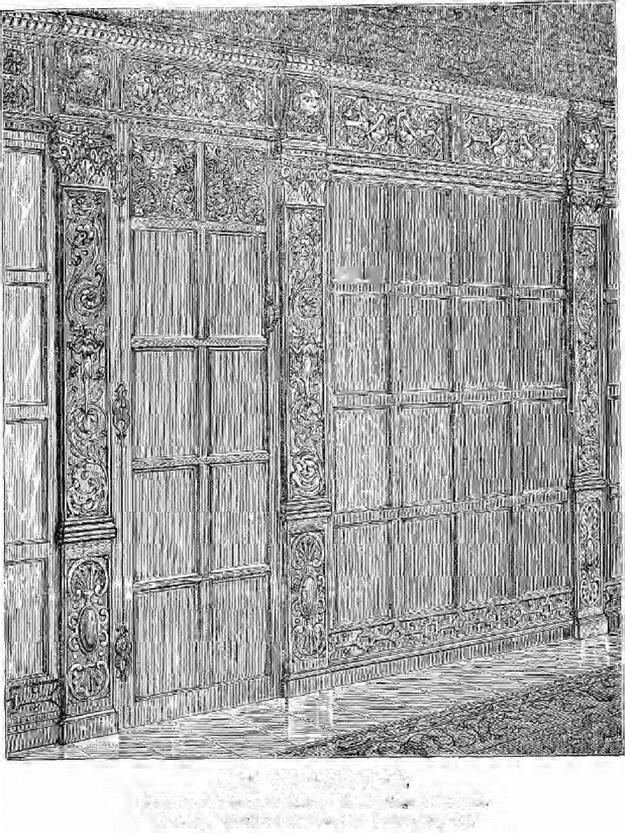

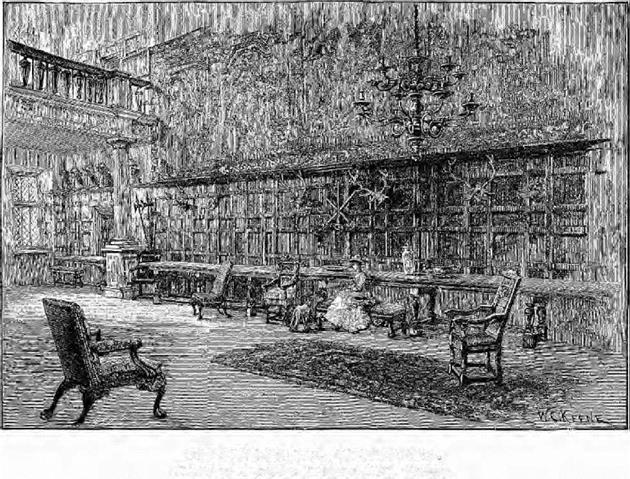

The oak panelling of rooms during the reign of Elizabeth was very handsome, and in the example at South Kensington, of which there is here an illustration, the country possesses a very excellent representative specimen. This was removed from an old house at Exeter, and its date is given by Mr. Hungerford Pollen as from 1550-75. The pilasters and carved panels under the cornice are very rich and in the best style of Elizabethan Renaissance, while the panels themselves, being plain, afford repose, and bring the ornament into relief. The entire length is 52 ft. and average height 8 ft. 3 in. If this panelling could be arranged as it was fitted originally in the house of one of Elizabeth’s subjects, with models of fireplace, moulded ceiling, and accessories added, we should then have an object lesson of value, and be able to picture a Drake or a Raleigh in his West of England home.

|

|

A later purchase by the Science and Art Department, which was only secured last year for the extremely moderate price of £1,000, is the panelling of a room some 23 ft. square and 12 ft. 6 in. high, from Sizergh Castle, Westmoreland. The chimney piece was unfortunately not purchased, but the Department has arranged the panelling as a room with a plaster model of the extremely handsome ceiling. The panelling is of richly figured oak, entirely devoid of polish, and is inlaid with black bog oak and holly, in geometrical designs, being divided at intervals by tall pilasters fluted with bog oak and having Ionic capitals. The work was probably done locally, and from wood grown on the estate, and is one of the most remarkable examples in existence. The date is about 1560 to 1570, and it has been described in local literature of nearly 200 years ago.

While we are on the subject of panelling, it may be worth while to point out that with regard to old English work of this date, one may safely take it for granted that where, as in the South Kensington (Exeter) example, the pilasters, frieze, and frame-work are enriched, and the panels plain, the work was designed and made for the house, but, when the panels are carved and the rest plain, they were bought, and then fitted up by the local carpenter.

|

|

|

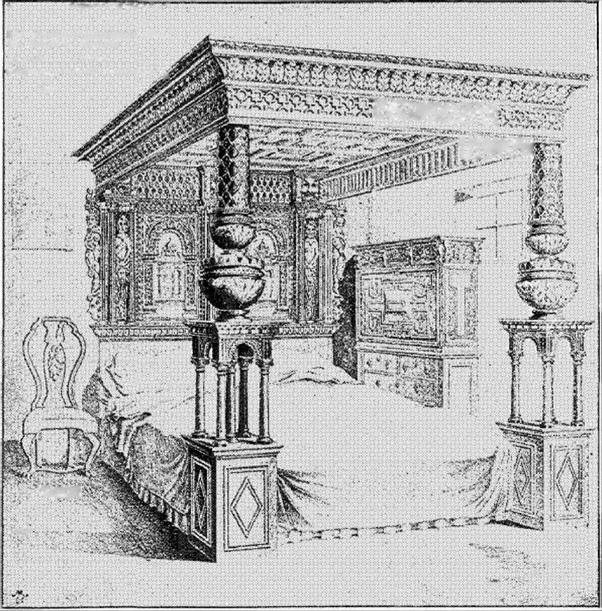

Another Museum specimen of Elizabethan carved oak is a fourpost bedstead, with the arms of the Countess of Devon, which bears date 1593, and has all the characteristics of the time.

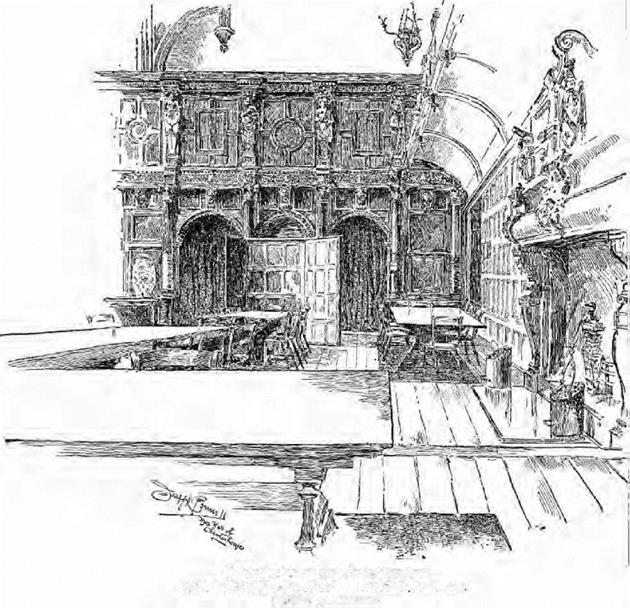

There is also a good example of Elizabethan woodwork in part of the interior of the Charterhouse, immortalised by Thackeray, when, as "Greyfriars," in "The Newcomes," he described it as the old school "where the colonel, and Clive, and I were brought up," and it was here that, as a "poor brother," the old colonel had returned to spend the evening of his gentle life, and, to quote Thackeray’s pathetic lines, "when the chapel bell began to toll, he lifted up his head a little, and said ‘Adsum!’ It was the word we used at school when names were called."

This famous relic of old London, which fortunately escaped the great fire in 1666, was formerly an old monastery which Henry VIII. dissolved in 1537, and the house was given some few years later to Sir Edward, afterwards Lord North, from whom the Duke of Norfolk purchased it in 1565, and the handsome staircase, carved with terminal figures and Renaissance ornament, was probably built either by Lord North or his successor. The woodwork of the Great Hall, where the pensioners still dine every day, is very rich, the fluted columns with Corinthian capitals, the interlaced strap work, and other details of carved oak, are characteristic of the best sixteenth century woodwork in England; the shield bears the date of 1571. This was the year when the Duke of Norfolk, who was afterwards beheaded, was released from the Tower on a kind of furlough, and probably amused himself with the enrichment of his mansion, then called Howard House. In the old Governors’ room, formerly the drawing room of the Howards, there is a specimen of the large wooden chimney piece of the end of the sixteenth century, painted instead of carved. After the Duke of Norfolk’s death, the house was granted by the Crown to his son, the Earl of Suffolk, who sold it in 1611 to the founder of the present hospital, Sir Thomas Sutton, a citizen who was reputed to be one of the wealthiest of his time, and some of the furniture given by him will be found noticed in the chapter on the Jacobean period.

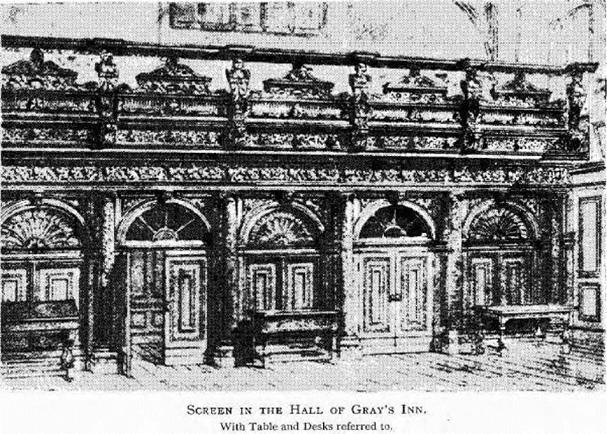

There are in London other excellent examples of Elizabethan oak carving. Amongst those easily accessible and valuable for reference are the Hall of Gray’s Inn, built in 1560, the second year of the Queen’s reign, and Middle Temple Hall, built in 1570-2. An illustration of the carved screen supporting the Minstrels’ Gallery in the older Hall is given by permission of Mr. William R. Douthwaite, librarian of the "Inn," for whose work, "Gray’s Inn, its History and Associations," it was specially prepared. The interlaced strap work generally found in Elizabethan carving, encircles the shafts of the columns as a decoration. The table in the centre has also some low relief carving on the drawer front which forms its frieze, but the straight and severe style of leg leads us to place its date at some fifty years later than the Hall. The desk on the left, and the table on the right, are probably later still. It may be mentioned here, too, that the long table which stands at the opposite end

of the Hall, on the dais, said to have been presented by Queen Elizabeth, is not of the design with which the furniture of her reign is associated by experts; the heavy cabriole legs, with bent knees, corresponding with the legs of the chairs (also on the dais), are of unmistakable Dutch origin, and, so far as the writer’s observations and investigations have gone, were introduced into England about the time of William III.

Dl. NI. VG HaIL in THE CUAJlTERHClUSt.

Dl. NI. VG HaIL in THE CUAJlTERHClUSt.

fVherritiR Chi: Scrcr. n – in.-і from of Minatrel. V (jsllerv, diuitl 157г

Pl’.UOil F-[.-l^iVD£ I HAS.

|

|

The same remarks apply to a table in Middle Temple Hall, also said to have been there during Elizabeth’s time. Mr. Douthwaite alludes to the rumour of the Queen’s gift in his book, and endeavoured to substantiate it from records at his command, but in vain. The authorities at Middle Temple are also, so far as we have been able to ascertain, without any documentary evidence to prove the claim of their table to any greater age than the end of the seventeenth century.

The carved oak screen of Middle Temple Hall is magnificent, and no one should miss seeing it. Terminal figures, fluted columns, panels broken up into smaller divisions, and carved enrichments of various devices, are all combined in a harmonious design, rich without being overcrowded, and its effect is enhanced by the rich color given to it by age, by the excellent proportions of the Hall, by the plain panelling of the three other sides, and above all by the grand oak roof, which is certainly one of the finest of its kind in England. Some of the tables and forms are of much later date, but an interest attaches even to this furniture from the fact of its having been made from oak grown close to the Hall; and as one of the tables has a slab composed of an oak plank nearly thirty inches wide, we can imagine what fine old trees once grew and flourished close to the now busy Fleet Street, and the bustling Strand. There are frames, too, in Middle Temple made from the oaken timbers which once formed the piles in the Thames, on which rested "the Temple Stairs."

In Mr. Herbert’s "Antiquities of the Courts of Chancery," there are several facts of interest in connection with the woodwork of Middle Temple. He mentions that the screen was paid for by contributions from each bencher of twenty shillings, each barrister of ten shillings, and every other member of six shillings and eightpence; that the Hall was founded in 1562, and furnished ten years later, the screen being put up in 1574: and that the memorials of some two hundred and fifty "Readers" which decorate the otherwise plain oak panelling, date from 1597 to 1804, the year in which Mr. Herbert’s book was published. Referring to the furniture, he says:—"The massy oak tables and benches with which this apartment was anciently furnished, still remain, and so may do for centuries, unless violently destroyed, being of wonderful strength." Mr. Herbert also mentions the masks and revels held in this famous Hall in the time of Elizabeth: he also gives a list of quantities and prices of materials used in the decoration of Gray’s Inn Hall.

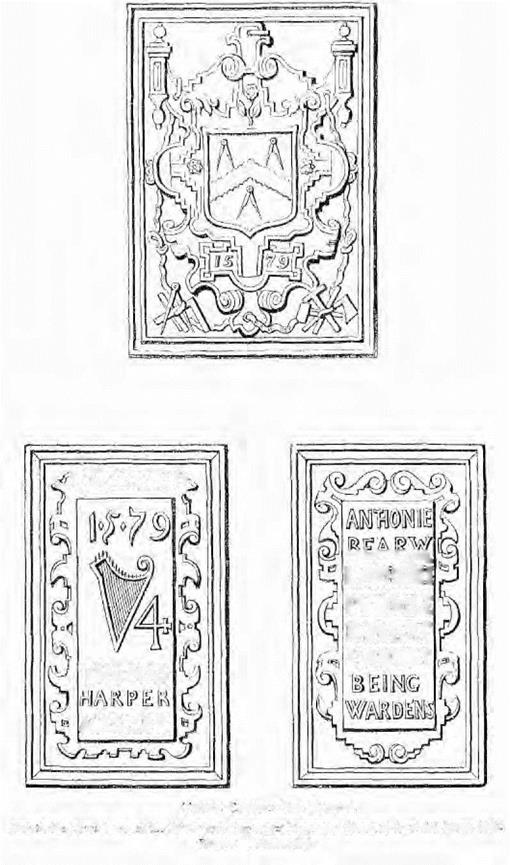

In the Hall of the Carpenters’ Company, in Throgmorton Avenue, are three curious carved oak panels, worth noticing here, as they are of a date bringing them well into this period. They were formerly in the old Hall, which escaped the Great Fire, and in the account books of the Corporation is the following record of the cost of one of these panels:—

"Paide for a planke to carve the arms of the Companie iijs."

"Paide to the Carver for carvinge the Arms of the Companie xxiijs. iiijd."

The price of material (3s.) and workmanship (23s. 4d.) was certainly not excessive. All three panels are in excellent preservation, and the design of a harp, being a rebus of the Master’s name, is a quaint relic of old customs. Some other oak furniture, in the Hall of this ancient Company, will be noticed in the following chapter. Mr. Jupp, a former Clerk of the Company, has written an historical account of the Carpenters, which contains many facts of interest. The office of King’s Carpenter or Surveyor, the powers of the Carpenters to search, examine, and impose fines for inefficient work, and the trade disputes with the "Joyners," the Sawyers, and the "Woodmongers," are all entertaining reading, and throw many side-lights on the woodwork of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

E-BooksDirectory. com

|

|

|

|

|

The illustration of Hardwick Hall shews oak panelling and decoration of a somewhat earlier, and also somewhat later time than Elizabeth, while the carved oak chairs are of Jacobean style. At Hardwick is still kept the historic chair in which it is said that William, fourth Earl of Devonshire, sat when he and his friends compassed the downfall of James II. In the curious little chapel hung with ancient tapestry, and containing the original Bible and Prayer Book of Charles I., are other quaint chairs covered with cushions of sixteenth or early seventeenth century needlework.

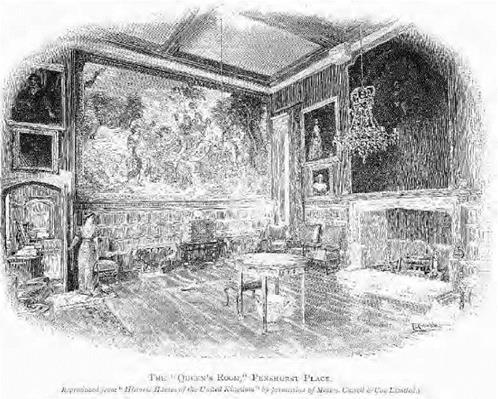

Before concluding the remarks on this period of English woodwork and furniture, further mention should be made of Penshurst Place, to which there has been already some reference in the chapter on the period of the Middle Ages. It was here that Sir Philip Sydney spent much of his time, and produced his best literary work, during the period of his retirement when he had lost the favour of Elizabeth, and in the room known as the "Queen’s Room," illustrated on p. 89, some of the furniture is of this period; the crystal chandeliers are said to have been given by Leicester to his Royal Mistress, and some of the chairs and tables were sent down by the Queen, and presented to Sir Henry Sydney (Philip’s father) when she stayed at Penshurst during one of her Royal progresses. The room, with its vases and bowls of old oriental china and the contemporary portraits on the walls, gives us a good idea of the very best effect that was attainable with the material then available.

THE ENTRANCE HALL, HARDWICK HALL

THE ENTRANCE HALL, HARDWICK HALL

P£htoo of Fvpmtvjis. Jacoshan, XVII. Свитч**.

Richardson’s "Studies" contains, amongst other examples of furniture, and carved oak decorations of English Renaissance, interiors of Little Charlton, East Sutton Place, Stockton House, Wilts, Audley End, Essex, and the Great Hall, Crewe, with its beautiful hall screens and famous carved "parloir," all notable mansions of the sixteenth century.

To this period of English furniture belongs the celebrated "Great Bed of Ware," of which there is an illustration. This was formerly at the Saracen’s Head at Ware, but has been removed to Rye House, about two miles away. Shakespeare’s allusion to it in the "Twelfth Night" has identified the approximate date and gives the bed a character. The following are the lines:—

"SIR TOBY BELCH.—And as many lies as shall lie in thy sheet of paper, altho’ the sheet were big enough for the Bed of Ware in England, set em down, go about it."

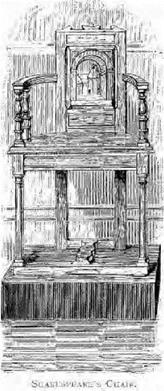

Another illustration shows the chair which is said to have belonged to William Shakespeare; it may or may not be the actual one used by the poet, but it is most

probably a genuine specimen of about his time, though perhaps not made in England. There is a manuscript on its back which states that it was known in 1769 as the Shakespeare Chair, when Garrick borrowed it from its owner, Mr. James Bacon, of Barnet, and since that time its history is well known. The carved ornament is in low relief, and represents a rough idea of the dome of S. Marc and the Campanile Tower.

We have now briefly and roughly traced the advance of what may be termed the flood-tide of Art from its birthplace in Italy to France, the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, and England, and by explanation and description, assisted by illustrations, have endeavoured to shew how the Gothic of the latter part of the Middle Ages gave way before the revival of classic forms and arabesque ornament, with the many details and peculiarities characteristic of each different nationality which had adopted the general change. During this period the bahut or chest has become a cabinet with all its varieties; the simple prie dieu chair, as a devotional piece of furniture, has been elaborated into almost an oratory, and, as a domestic seat, into a dignified throne; tables have, towards the end of the period, become more ornate, and made as solid pieces of furniture, instead of the planks and tressels which we found when the Renaissance commenced. Chimney pieces, which in the fourteenth century were merely stone smoke shafts supported by corbels, have been replaced by handsome carved oak erections, ornamenting the hall or room from floor to ceiling, and the English livery cupboard, with its foreign contemporary the buffet, is the forerunner of the sideboard of the future.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE GREAT BED■ OF WARE-

Foiijttlerly aL the Saracen’s [TeutO, Wire, but now at Rye House, ВгАхЬиигпе, Herti,

Period: XVI. Century,

Carved oak panelling has replaced the old arras and ruder wood lining of an earlier time, and with the departure of the old feudal customs and the indulgence in greater luxuries of the more wealthy nobles and merchants in Italy, Flanders, France, Germany, Spain, and England, we have the elegancies and grace with which Art, and increased means of gratifying taste, enabled the sixteenth century virtuoso to adorn his home.

|

|

|

|