As a broad time context following there is a selection of urban development milestones, commenting on them their particularities in relation to the landscape first represented as a menace from outside and later as an injured party of urban growth.

2.1 Walled towns

When ancient settlements, through the specialization of jobs, grew into villages and then into towns, different reasons drove their inhabitants to identify and separate themselves from the surrounding fields. As a physical consequence, a strong and conspicuous feature emerged in the landscape: the defensive wall. Undoubtedly this feature was seen, recognized and perceived by people who approached them or worked in agricultural fields outside the towns, but probably it was not interpreted as part of the landscape, because that concept did not exist in the vocabulary or imagination of older civilizations.

Of course, by the time that walled cities flourished, landscape was not a planner’s worry, or even a simple purpose. The walls, promoted mainly by military and political causes, as well as every huge human construction, had a strong effect on people’s perception of landscape, although this was an unconscious perception. Nature was "there", or outside the town, and life, property and safety were "here" inside the town.

"Sumerian cities…from the III millennium B. C…. were surrounded by a wall and a moat that defended them and separated – for the first time – the natural open environment from the close city environment (L., 1977)"

The wall signified another difference as well. The dominant people lived inside while the subjugated people lived and/or worked outside. That idea persisted worldwide, and still persists in many places, for a very long time up to the moment when "suburbia" started to mean economic power and high status outside. That is to say that there are at least two ways to inhabit the non-urban territory that surrounds the cities core: one not being able to reach their standards and the other passing those standards. Both ways are observed, in a strong contrast in many cities today.

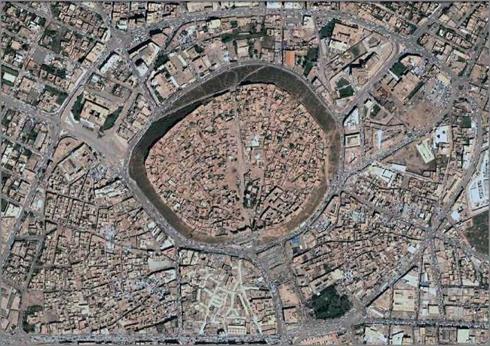

In some cases, such as Arbela (or Erbil) in Mesopotamia (Figure 1), this division was totally defined by walls, while in Babylon and many other ancient cities the walls that conformed the border were combined with natural or managed watercourses. An outstanding and surprising case is that of Carcassonne, in France, surrounded by a double wall, with one quite close to the other. Some of the walled cities remained firmly throughout the centuries while some others underwent several changes and re-constructions. One such a case is that of the city of Athens, quite didactically expressed by Benevolo in his five volumes work Design of cities (1977).

|

Fig. 1. Arbela (or Erbil) a walled city inhabited continuously since its creation, B. C., up to date. Source Google earth 2011. |

That practice of strong separation transcended for centuries, and even though the thinking that something appreciated should be enclosed flourished in managed landscape – or better garden – through the middle ages orthos conclusus, and later the green labyrinths, or portions of nature locked up to be enjoyed only by a few people, like an individual property.

Once the social and political circumstances that caused the growth of walled towns had changed and overcrowding became a problem, the surroundings had to be occupied. However, the feeling of being unprotected promoted in some cases the construction of a new peripheral wall that would symbolize security. This second wall, though, was not as fortified as the first.

By the time when walled cities reached their peak in Asia and Europe, in the land that later would be named America, a very different thinking guided its inhabitants relation to the earth. They used to define themselves, and still remnant tribes do, as part of nature. This thought is quite nicely expressed by the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, who states, even opposed to the Catholic believe of God’s Ten Commandments, that God forgot the eleventh commandment: You will love and will respect nature to which you belong. (Galeano, 1994).

The conquering army’s power defeated the natives’ thought power and a result of that was the establishment of a walled city with the most extensive fortifications in South America: Cartagena de Indias, which is still the best example today. (Figure 2). Described as the masterpiece of Spanish military engineering in America and located on the Atlantic coast to the north of Colombia, the walled part of the city was declared by UNESCO as a Historic and Cultural World Humanity Heritage in 1984.

|

Fig. 2. A portion of the present urban area of Cartagena de Indias and, within the circle, the ancient walled city. Source: Google Earth 2012 |

Surrounded by water, although not rectified or geometrically transformed as had previously happened in other walled cities, in Cartagena de Indias the sea and the swamp offered the right environment to settle an urban core defended by bodies of water, which were reinforced by the infallible wall.

That inherited defensive attitude, that had repercussions on people’s perception and interpretation of their relation to landscape, still remains in urbanism practice, particularly within residential units or condominiums and may be seen everywhere in Colombia. This phenomenon results in a kind of landscape that wastes the wide richness of local landscape and hurts the local landscape identity.