![Water is universal Подпись: -Q]](/img/1316/image133_2.gif)

to gravity. And this actually does occur at first. But after a very short time the thread of water changes its course: it starts to swing rhythmically to the right and left, producing a meandering trail of water that changes constantly. Rivulets, streams and rivers form these meanders, leave loops behind and reshape their banks. Entire landscapes are shaped in this way.

Different structures like pools, channels or vessels offer themselves for experiment. Flexible, changeable materials like clay or sand are particularly suitable for studies of this kind.

If you wish to determine the inner movements of a body of water, you need to add fine particles or dye. To make surface currents visible you should add lycopodium (club-moss spores), and for three-dimensional movement in water the addition of magnesium dust or a dye like potassium permanganate is recommended. The closer the dye is to the same specific gravity as the liquid, the more clearly the movement can be seen, even when flowing slowly.

The water workshop: working with real models

It is sensible and advantageous when working out designs with water to work with it in a real form as well. Experience has taught us this: fountain projects, flow details or flow channels that are really interesting and appropriate to water cannot be developed and calculated theoretically, they need experiment, frequently on the scale of one to one.

We are constantly discovering that water is our best teacher. Despite all prior considerations and even with a great deal of experience: water does not always behave as expected. Corrections and constant new experiments are the principal task. The designs improve gradually and start to carry the signature of the water itself.

A water workshop can be simple and robust. In any case it should be well enough equipped to allow a large number of the desired experiments with water to be carried out. It is astonishing how directly and surely water itself holds the mirror up for the designer. In practice we are constantly surprised how immediately convincing ideas can be acquired in this way.

Linking themes

This is particularly true today: themes involving water are complex and are always directly related to other themes and specialist areas. Isolated water-features that are self-sufficient are no longer in vogue and on close consideration historical fountain complexes always existed in a context of many other functions. They provided drinking and utility water, were a sound instrument for the town, especially at night, and they formed a social focal point where people could meet.

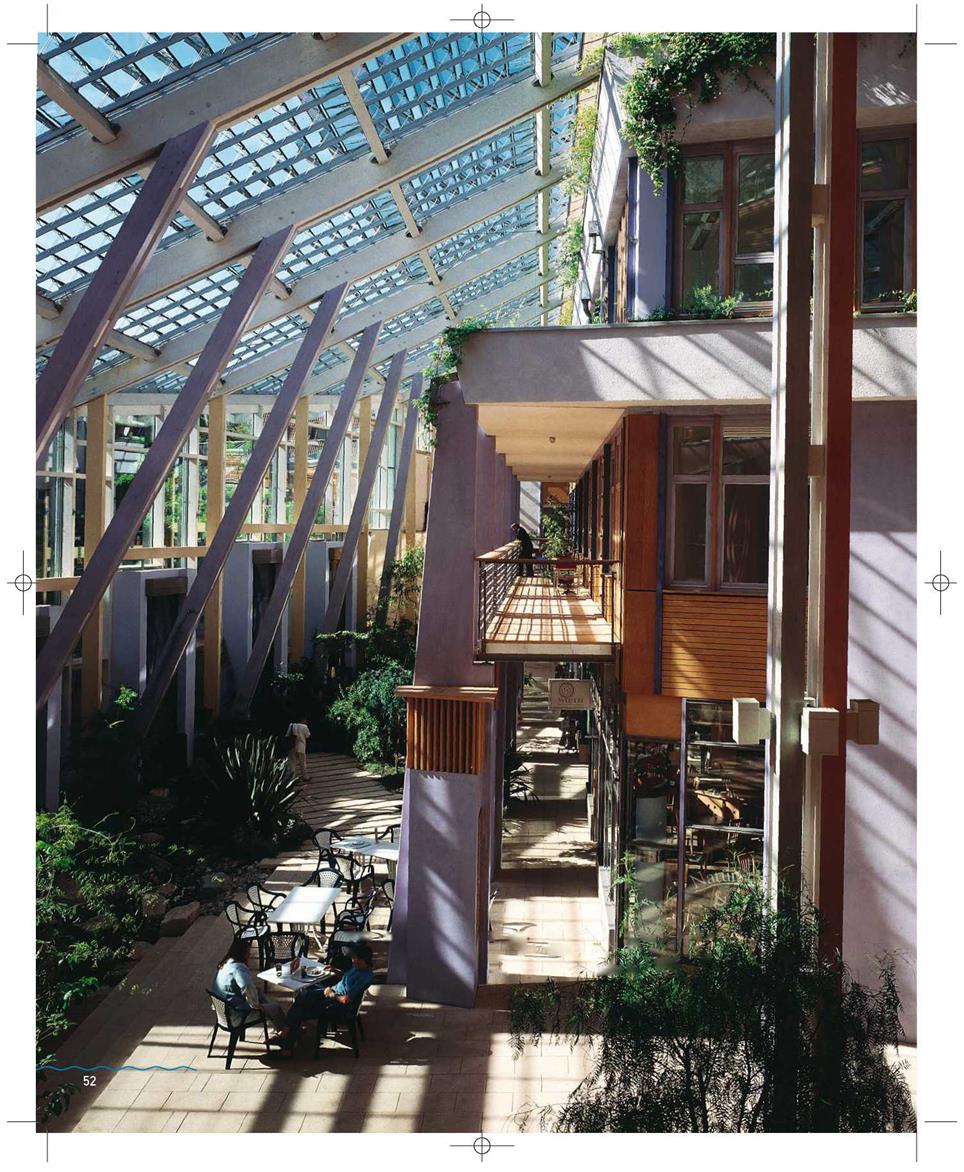

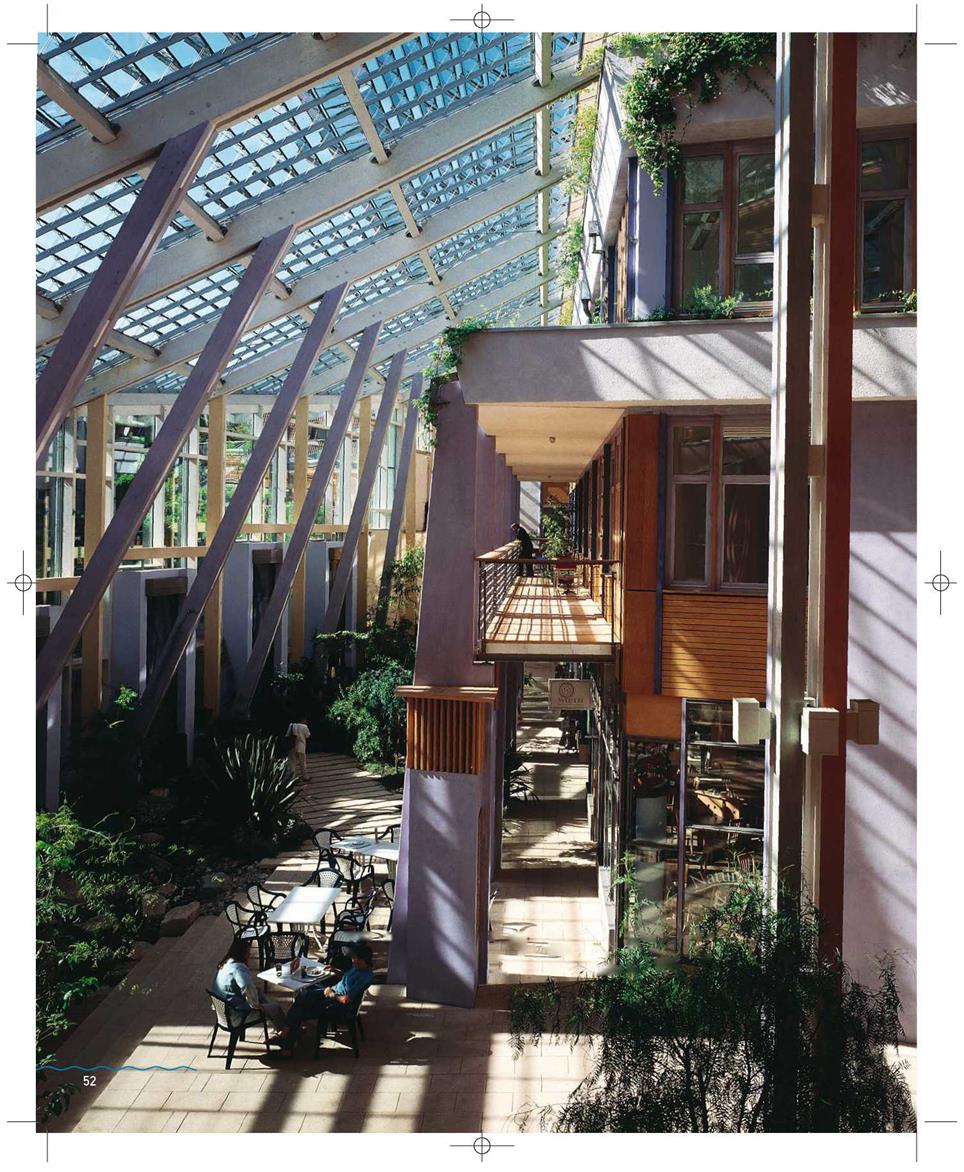

Water themes today: the need for links. Water influences our sense of well-being in towns and in buildings, it affects the humidity, the temperature, the cleanness of the air, the climate. Water can be used in such a way that it filters, cools or warms the outside air and regulates humidity. Experience in the Prisma in Nuremberg or in the Nikolaus-Cusanus-Haus show new ways forward for air-conditioning.

Smell and taste make places unmistakable. It is one of the strongest impressions available if you recognize a town, a location, a season through its smell, and here too water can mediate. The somewhat sickly smell of the haze on a late summer’s morning in Venice or the fragrance of blossom by the Seine in Paris in the spring.

The sounds of water against street noise. They are soothing, and compensate for urban stress, never mind the decibel levels. Robert Woodward opened his Opera Cafe near a busy highway, but surrounded it with a cascade of water, so that you can enjoy your cappuccino in the middle of it, undisturbed and in the best of spirits. And in downtown San Francisco you can escape from the noise of the city and lie down and relax on a lawn by the waterfalls of the Martin Luther King memorial fountain. But even unspectacular small water features can make spaces magical with their special sounds. In the foyer of L’Aubier, a Swiss mountain hotel, a stream of water activates a musical fountain. Water is the artist, the fountain is the musical instrument.

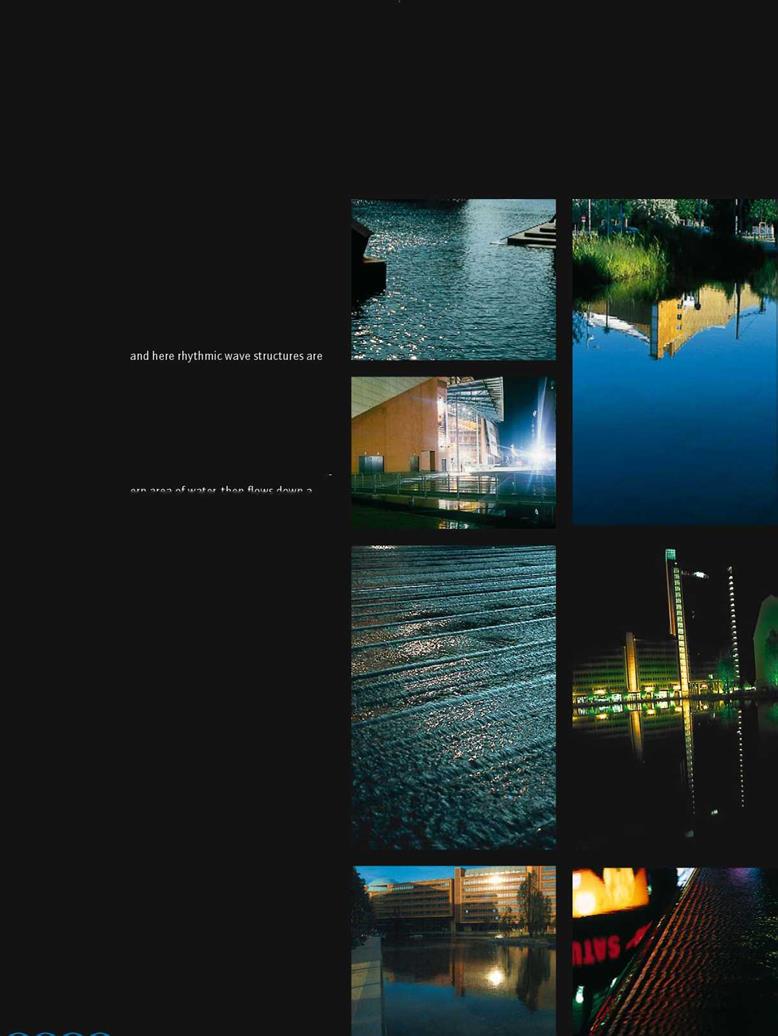

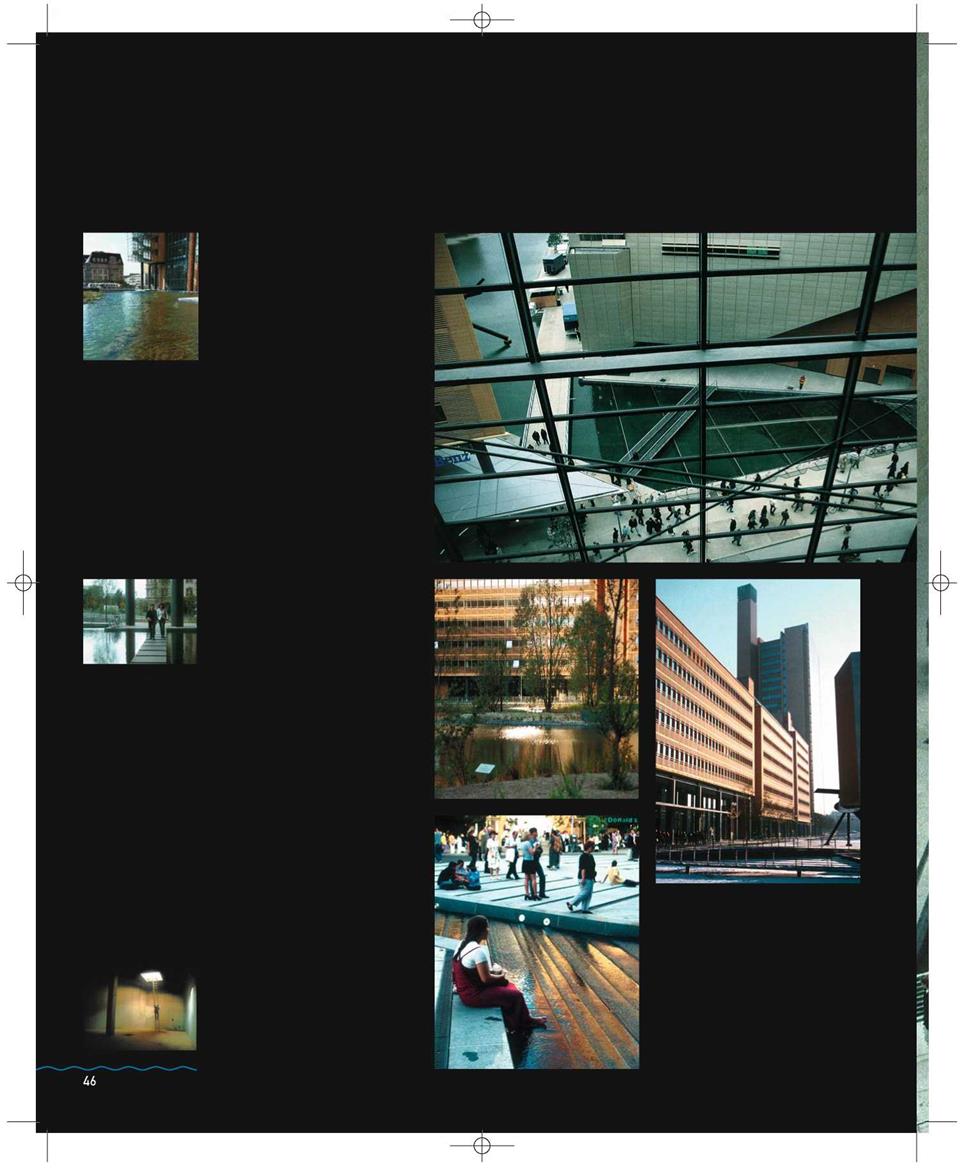

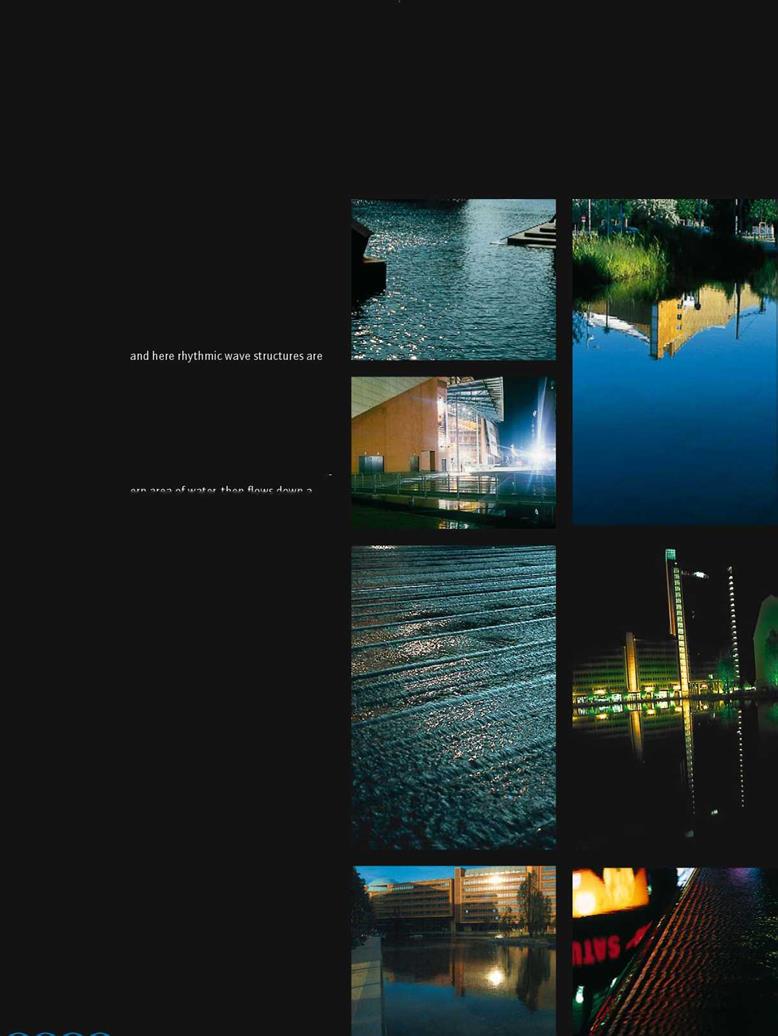

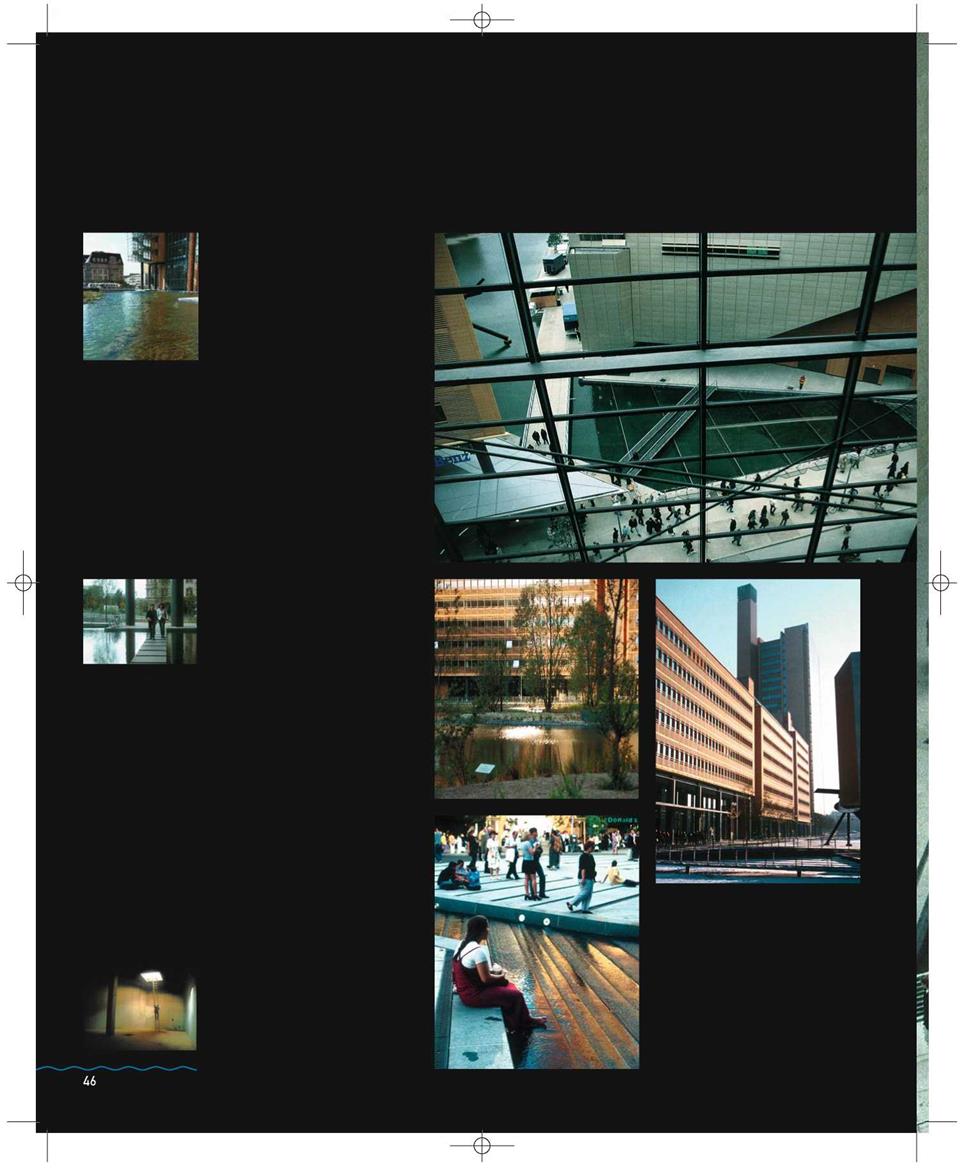

Moving light brings spaces to life. Water distorts, refracts and reflects. It distributes incident light dynamically in connection with its own movement. Working purposefully with light effects and thus using the water surface as an instrument is demonstrated by the examples of urban water in Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, by the finely differentiated waves and watercourses in Gummersbach or the major water scene in Hanno – versch Munden. Here the art is to move the water in such a way that it supports the light installation.

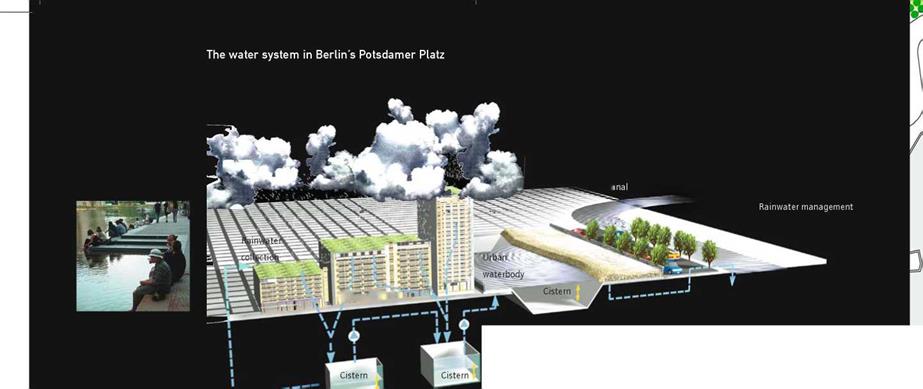

Water at the wrong time and in the wrong place causes extra-high tides, floods, erosion and destruction, but also droughts, a lack of groundwater, dried-up aquifers and biotopes, and thus the destruction and elimination of a rich variety of flora and fauna. Water projects have to address creating a balance in water management. Retention, purification, evaporation and infiltration must of course be integral elements in a municipal water programme. Rain retention in the Kronsberg district of Hanover, the green roof to retain and purify rainwater on City Hall in Chicago and the use, storage and integration of water in the new Potsdamer Platz development in central Berlin all count towards this.

And finally, water creates atmosphere, something that is vital to our towns and cities if they are to be individual,

unmistakable and easily recognized, with a sense of being home. This is a difficult set of phenomena to describe, and has something to do with the spiritual quality of a place, defining life and movement, which is something that water can convey directly like no other element. Interdisciplinary work and thought are needed to link themes together. The questions posed and the themes addressed go beyond the bounds of a single subject as far as the qualities of water are concerned, and this requires a new planning strategy.

Planning instruments and planning culture

Even since people have organized their surroundings, tilled fields, founded villages and settlements, they have had to make water into something they can use, and regulate water management. Thus water planning is one of the oldest driving forces in urban development, and gave rise to important engineering constructions at a very early stage in history. But these were always an expression of an attitude as well, of philosophy, myth and religion, they were presented aesthetically. Today it is scarcely possible to understand any longer how closely the fields of art, architecture and engineering were linked until the late Middle Ages: they formed a unit. An outstanding example of this kind of interdisciplinary work with water is an artist like Leonardo da Vinci.

In the course of history these fields have developed, become more specialized and moved apart. A real interplay of planning disciplines is rarely found, if at all. Architects like using choice sites near water, but it is exceptional for them to address other water themes and they usually see water as a hostile force that damages their buildings. Engineers are inclined to find purely technical solutions to questions about water, and often seem to be following a marked urge to convince others and themselves that those solutions are indispensable. Artists seldom make reference to this element that determines life and the environment. They often use water decoratively, as part of their own self-presentation system.

But water problems in town and in the countryside, which are increasing the world over – problems like surface and groundwater pollution, floods, drought and climatic change require holistic strategies and planning. Causes can often be found in the fact that such problems are linked with our social values and customs. Isolated repairs are of limited use only, in terms of both space and time. We are becoming increasingly aware of the necessity to work sustainably and far-sightedly with water. In the future planners will be increasingly required to put water itself back in a consistent context. This is the only appropriate way for dealing with its qualities and diversity. And here are some ideas for a start on integrated planning:

Global and local: Water always creates a relationship between detail and the whole. Each individual drop contributes to the balance of the earth’s climate. Water projects become valuable when they help this process and can show that the place is being addressed, and how it is connected with the world around it.

Social significance: Water always stands for exchange and openness as well. It reflects fairness or injustice between human beings. Planning is successful if the cultural and social needs of the individual users are met and societies are regulated communally, and are expressed correctly.

Citizen involvement and participation: The way the most important substance for life on earth is handled is determined in many democratic countries by the priorities set by citizens. Water projects should include citizens and later users in planning and decision-making to as large an extent as possible.

Commitment and participation: It is important to promote and stimulate people’s own creativity, as water is full of imagination, and a water-playground is one of the most popular places there are, and not just for children. Planning should offer people a chance to exert their influence and to suggest and agree to open possibilities for play.

Demonstrating sustainable environmental technologies: This means that processes for purifying and treating water, for avoiding floods and other such things should not be concealed, but wherever possible be presented openly and creatively. Retaining and managing rainwater in a new residential area can be integrated into open spaces within the planning process and become part of the architecture.

Admitting multi-functionality: This can be seen everywhere in nature. Why must a rainwater retention facility be used for this purpose only? Skilful planning means that play and sunbathing areas can be built in for when the weather is dry, as they won’t be used for those purposes when it is raining anyway.

Integrated planning will always combine several water themes where possible. There are many of these, and they often do not exclude other types of use. But this can only succeed when everyone involved in the planning process really does use interdisciplinary working practices. Tolerance alone is nothing like sufficient here. The specialist disciplines should overlap in every individual involved, and every individual in a team should be aware of at least some elements of the others’ specialist fields.

To do justice to water we have to go into the waterworld ourselves, experiment with it and learn to think in an integrated and interdisciplinary way about its flow and flexibility.

To do justice to water we have to go into the waterworld ourselves, experiment with it and learn to think in an integrated and interdisciplinary way about its flow and flexibility.

|

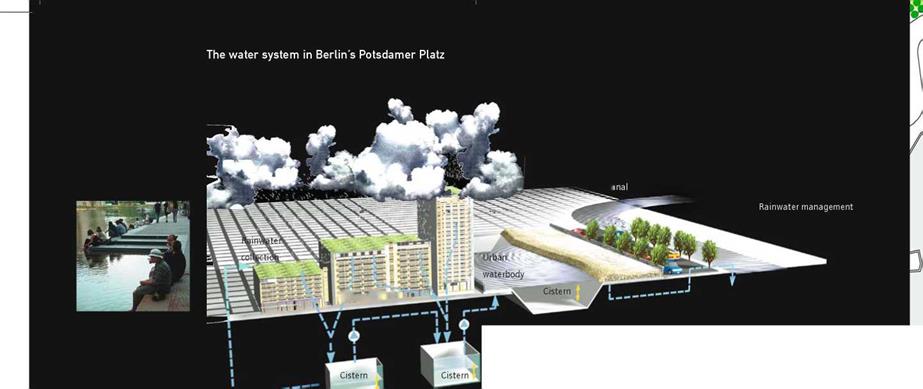

The water system in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz

|

|

|

Question after question cropped up on the top of the red Infobox in the middle of Potsdamer Platz, and deep abysses opened up in front of it. Colourful hard hats moved as though on invisible strings, and so did the lorries, full or empty after they had tipped their loads out, divers poured the cellar foundations into the groundwater at night, coloured piping ran to and fro over streets and excavations, cranes raised and lowered everything that was needed inside and outside, up there or down here. Expectations of the completed Potsdamer Platz were immense, and the problems on what was once Europe’s largest building site were highly complicated. Two demands: people were not just supposed to work here, they were supposed to spend their leisure time here as well.

A vibrant urban construct was to be created, which is difficult in the shadow of towering company headquarters. And the intention of setting high ecological standards for the project had caught on as well. There were the following problems: very little space was available for leisure provision, and it was subject to all sorts of demands and wishes. What devices for planning open space, what themes can be used to do justice to a lot of people and the urban design at the same time, and finally to come close to meeting ecological aims?

Herbert Dreiseitl had already worked on Potsdamer Platz immediately after the Wall came down, with an Anglo-German planning team. The theme of water as a defining element in the open space had convinced both the Senate and the investors from the outset. First of all the design possibilities caught their imagination, and secondly they were fired by the chance of meeting the ecological challenges. The suggestion that rainwater should be used for flushing toilets and watering green areas was met with interest. The same was true of the idea of using the rainwater that collected in the underground tanks to feed a water

|

|

|

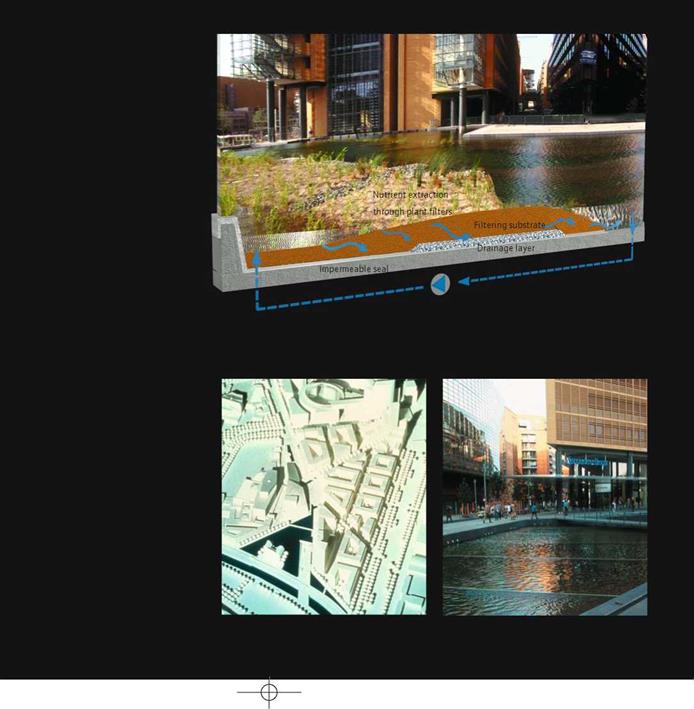

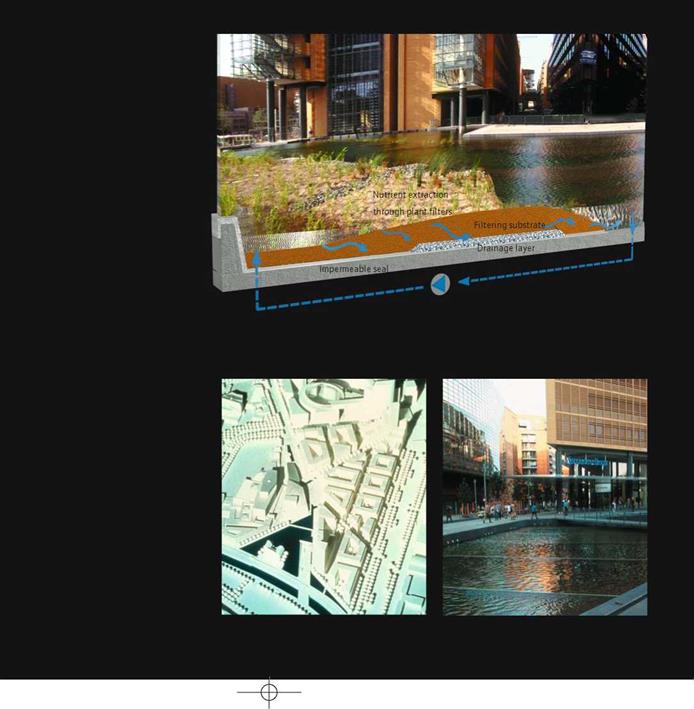

Visible water cleansing through a planted biotope does not just stabilize the water quality, but also adds a strikingly dune-like note to the austere urban landscape.

|

|

|

No parapet or railing – stepping stones lead over the expanse of urban water.

|

|

|

|

Even when frozen over in winter, the water provides an interesting context for the architecture.

|

|

|

Everything comes together here: active life, prestigious architecture and a filigree pattern of water features that contain in fact just collected rainwater.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

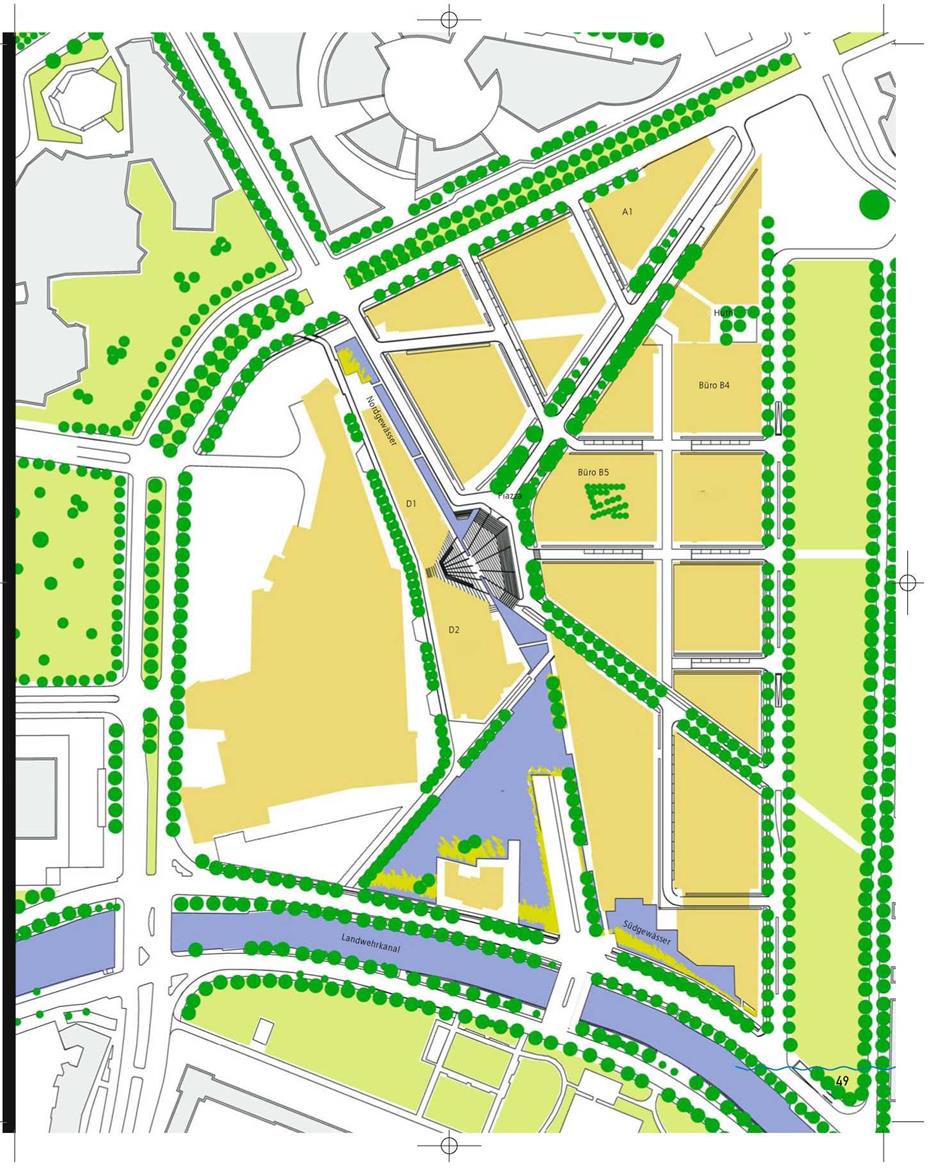

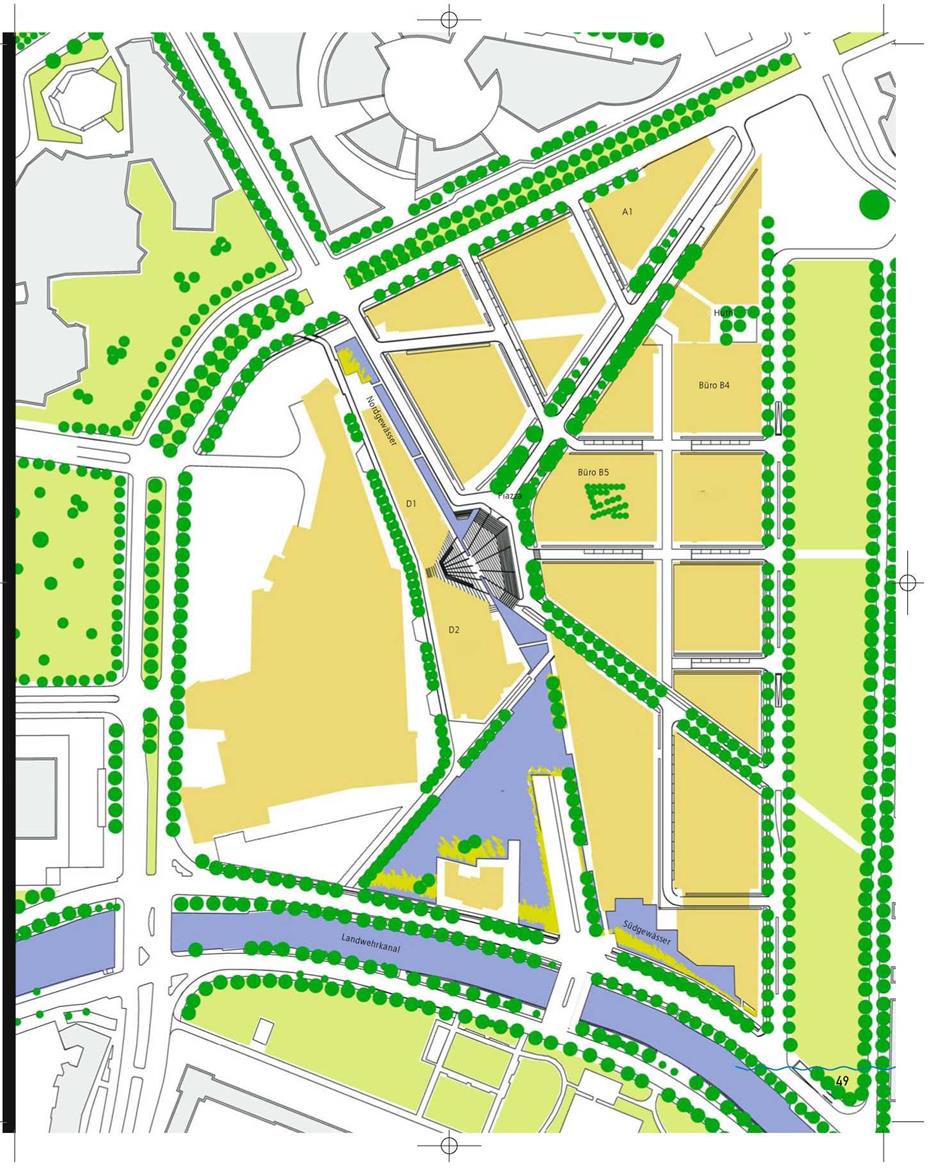

Overall plan of the Potsdamer Platz site with

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Water storage in cisterns

|

|

|

Flow simulation analysing how the water acts within the geometry of the pool. This made it possible to optimise the most effect locations for the inlet and outlet points.

|

|

|

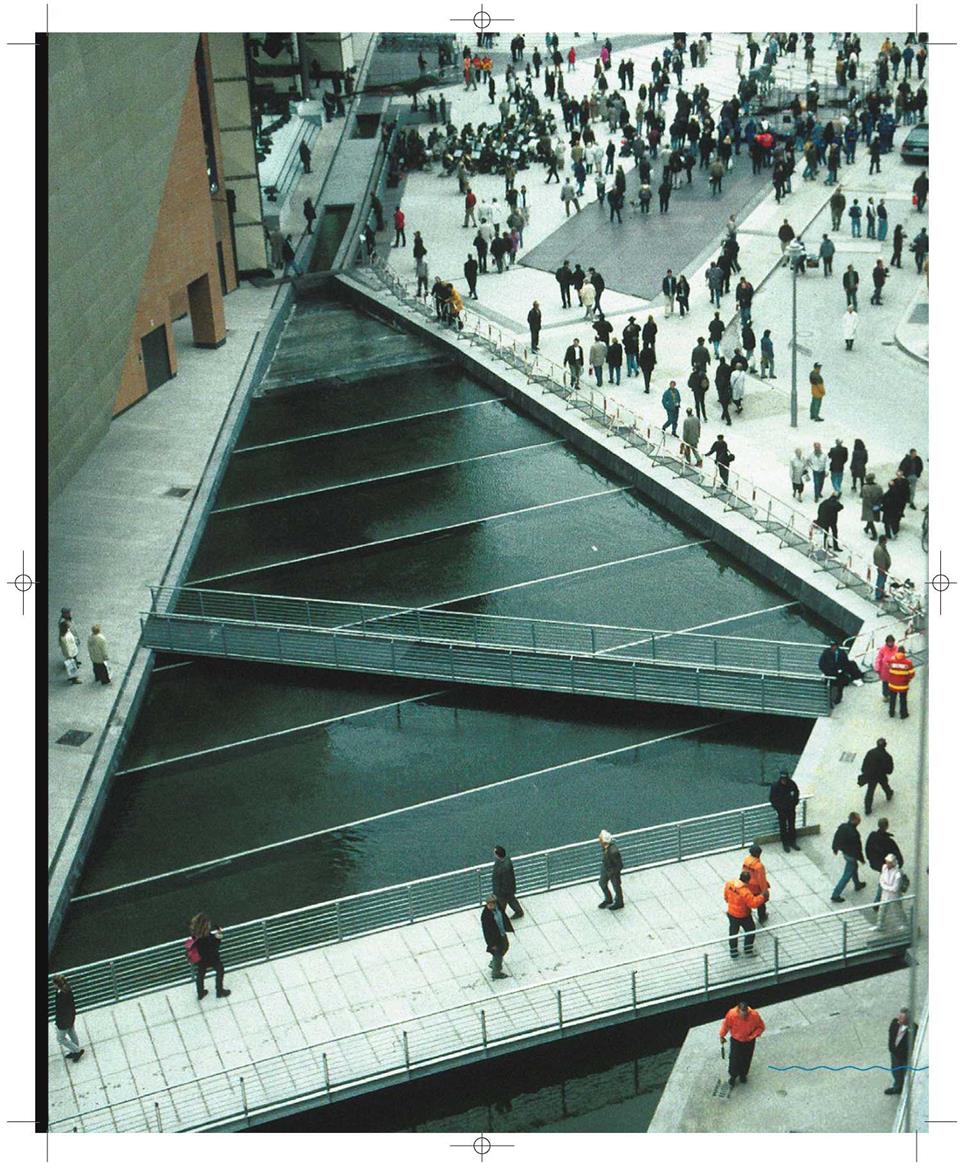

system that would include a narrow pool on the northern side, one in the piazza, the large main area of water and the southern area of water. Additionally, this offered the opportunity not to lowerthe groundwater during the building phase and to make an intermediate collection of all the rainwater that fell on the buildings and slowly feed it into the Landwehrkanal. A complex computer simulation was used to predict that the Land – wehrkanal would only be compelled to absorb heavily increased amounts of precipitation three times in ten years; this is based on the approximate drainage figures for an unsealed plot.

To guarantee this, the system must carry sufficient buffer capacity. This is provided in the first place by five underground tanks with a total volume of 2,600 cubic metres, of which 900 cubic metres are left free in their turn for cases of heavy precipitation. In addition to this, the main area of water can still offer a reserve of 15 centimetres between the normal and the maximum water level, which provides a storage buffer of 1,300 cubic metres. A key feature was the water resources that were discovered above the turbidity level of the main area of water. Solids can start to settle in the underground tanks before the water flows out of source vessels on the banks of the south and main areas of water, through planted purifi-

|

|

|

Section detail through cleansing biotope

|

|

|

|

|

The water system in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz

|

|

|

Scharoun’s Berlin Philharmonie is reflected in the crystal clear water.

|

|

|

cation biotopes, where it is cleaned biologically and chemically. If necessary, technical filters can also be used, which will remove any floating algae in the summer months.

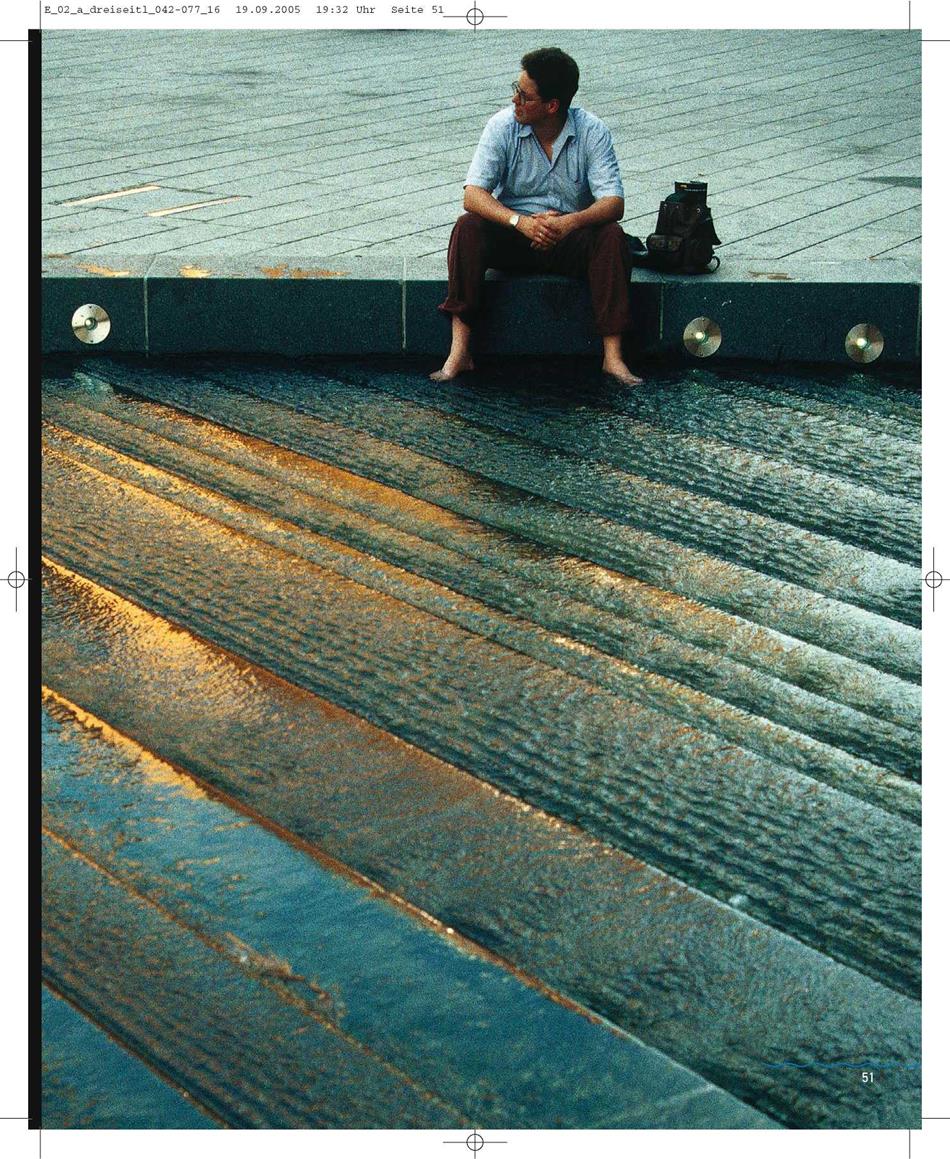

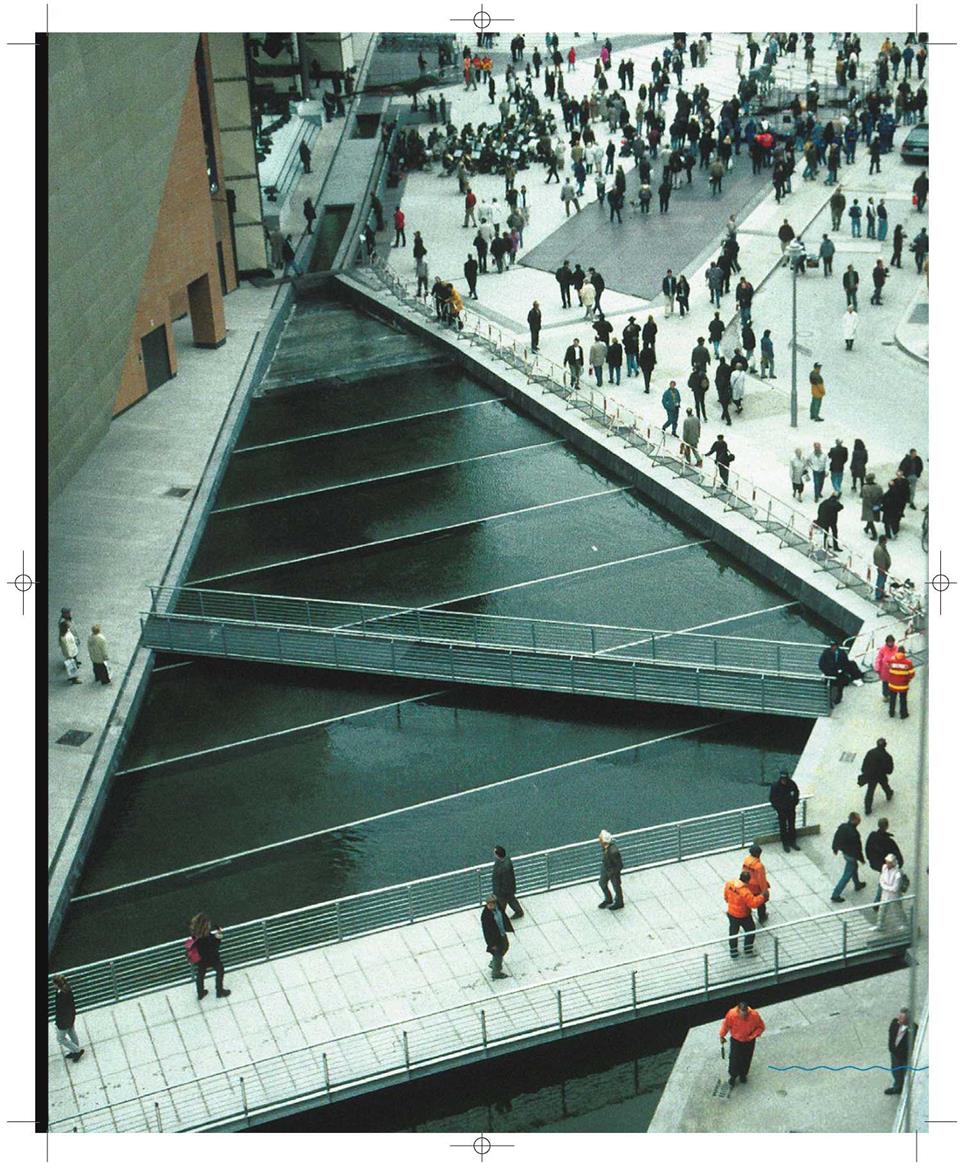

In Marlene-Dietrich-Platz water flows in intricate patterns to the lowest point in the piazza. The water glides of flow – steps from the main expanse of water,

|

|

|

Steps and sculpture platform in the mobile surface of the water

|

|

|

formed. A detail that is accurate to a

|

|

|

|

Architecture bathed in light, reflected and dissolved in the water

|

|

|

Turbulent rhythmic structures

|

|

|

The water surface is a mirror at night

|

|

|

Stippled waves, created by the tiniest possible change in levels, alternate with smooth and turbulent areas. The interplay of wind, nature and art produces visual colour games.

|

|

|

VU -7: ‘ ■

|

v ^

|

|

1 ■ -*зУі,’i?

* •

|

|

4 _

|

Pft -7^ – j

|

jr3

|

|

|

—. ^

|

Ш bt,

|

;•# – f.

•

|

|

Water is far from being just a designer’s resource or a material: it begs to have its vital possibilities rediscovered. This starts at the beginning of the planning process for water projects, and involves linking up and integrating elemental themes. Knowledge of water’s particular qualities as a material are needed, and often experiments need to be conducted to give a real idea of the result that will ensue.

Water is everywhere in our towns, in a labyrinthine system of concealed pipes. It is freely available, and can apparently be disposed of without difficulty. City-dwellers are usually only confronted with it at the various ends of the system in their houses or flats: coming out of the tap into the sink or washbasin, in the bath or under the shower, with the surge of the flush or when paying the water rates.

But nowadays it is rare to experience water in the open in our towns and cities – and yet it is increasingly in demand. Aesthetically presented and decoratively displayed, from a simple fountain to a showy water installation, it is appreciated as an invigorating element in front of and between the buildings.

Of course fountains and open waterways in towns and cities are nothing new. There is impressive evidence of them even from ancient times. They give us a sense of how closely urban design has always been linked with water and its use. This functional relationship can be traced from antiquity through the Middle Ages to modern times, and has made a lasting impact on the image of cities. Waterways for goods transport and other traffic, facilities for providing drinking water and removing sewage were crucial when choosing a location and helped to shape the ground plan of a town, the squares and streets. And here water was far more than something that simply had to be supplied and disposed of, it was presented artistically in all the great cultures, emphasized aesthetically and venerated. It created the atmosphere and expressed a living relationship between a town and its surrounding area. The way water is handled in towns shows more than the mere technical ingenuity of its citizens, it reflects myth and religion and shows the spiritual constitution of people living in a water culture.

This changed fundamentally during and after the industrial revolution: water and waterways were now increasingly brought under control. They were straightened, canalized, built over, buried and even filled in. Trusting entirely to the fact that all this would be technically possible. But this trust was broken by the floods, which came more and more frequently, and with increasing fury.

Now water is one of the key questions as far as the future of our world is concerned, as we have recognized that naturally available water supplies are finite, pollution is always just round the corner, and we are aware that water plays a complex role in the stability of eco-systems.

Water is the material basis of man’s relationship with his environment, and often stands as a symbol of it. It creates links and is in a state of permanent exchange in relation to warmth, climate, air, soil and gravity. Growth, metabolic change and vital functions are inconceivable without water. Water projects are perhaps so topical because they express a profound longing for life in all its vigour.

Technology and aesthetics are usually kept neatly apart in our brave new urban world as contradictions that cannot be bridged. They often seem to be as far apart as the various professions and specialist disciplines associated with them – and so the various training courses are neatly separated as well.

Unknown water

Although we could not survive from day to day without water, we are usually aware of it only superficially and at particular moments. Reduction to simple functions like cleaning, washing and waste disposal reduces the intricate interplay of water with our lives to simplified and imprecise images.

Planning and working with water seem simple at first as well – but even the first practical experiences can reveal unexpected and unfathomable depths, and other surprises. For example, water often does not flow in the way that is projected by the computer or on the drawing-board: a curtain of water falls quite differently from the way you anticipated, the desired wave patterns do not materialize, or are not as planned, and the ‘reflecting pool’ you hoped for reflects too rarely – or not at all. And it is also not rare to find that the quality of the water in a newly installed system leaves something to be desired, or a deposit of limescale spoils the look of the expensive natural stone basin. Other consequences of such mistaken assessments and ignorance at the planning stage are technical problems and excessively high running costs.

This is not a horror story, but unfortunately it is often the case – and there are a lot of architects, planners, artists and their clients who could tell you a tale about it, and who have foundered on one of these rocks. They then give up, following the motto ‘once is enough’, or are simply satisfied with going back to banal solutions that have been used all too often in the past.

And there are some places where new fountains and water sculptures can seem out of place or unnatural. This is a sign of approaches that have been worked out in theory, but have

nothing to do with the real qualities of water. Indeed there are times when people look at these fountains and sculptures and ask whether it wouldn’t have been better to leave the water out altogether. Every artist and planner realizes when designing a water feature that water needs a great deal of respect when you are working with it: it is mysterious, and likes for be investigated sensitively. It is easy to assess when looking at projects and works of art involving water how thoroughly the people planning it understood water. Did the water in the project become a mere side issue, or is this a successful installation that does justice to water and brings out its best qualities? Here at the latest you see whether the planner had real insight, and how sensitively the water has been handled.

First experience and approaches

The knowledge we acquire at school and from the rest of our education is often not enough to grasp water in all the richness of its many manifestations. You cannot get to the bottom of water with abstractions like chemical and physical formulae, as the ideas associated with them are often too static and distanced. Water is full of dynamism, and it needs a sense of movement in the thinking and ideas of the people dealing with it. Professions that handle water every day gain experience of this kind and know the special inner flexibility that is needed to work with water successfully.

There are all sorts of ways of getting closer to this amazingly flexible material. This includes a number of sports that make it possible to experience water directly and physically, using some quite simple aids: swimming, surfing or diving, to name but three. Sensitive observation of water in a landscape is particularly valuable.

Water and air: You have to start by watching what happens when it rains. The weather front approaches trailing a curtain in the sky, and the threads of rain dance in the wind like a fine veil. If you are lucky, different coloured layers appear in the depths, and sunlight is split into its spectrum in a rainbow. Whether it is a veil of rain, or mist and cloud formations – the images change constantly, influenced by temperature, humidity, air pressure and temperature variations. But water is visible in air only when droplets or ice crystals catch the light.

Surfaces: If droplets fall into a lake from trees on the shore, you see a number of eccentrically expanding rings of waves, that seem to pass through each other without having any effect. Perhaps you can see from stalks, twigs and objects how the waves are diverted there, then break on the shore or are driven back again.

Wave structures with different patterns appear in all places where different media meet, e. g. on the borderline between

water and air. Here dimension or scale has only a minor role to play. A fine breath of air, the slightest stimulus is enough to produce an infinite number of rhythmic patterns in a pool or the sea, or even in a little basin. Here again it is worth noticing the play of light, as it is only reflections of the sky, the landscape or of objects that make the wave structures visible to us.

There are planes that appear on borders, and also waves, that are only seldom perceptible. This also includes horizontal interfaces between bodies of water, for example with different densities. These are caused by differences in temperature or different salt contents. We are often aware of them when swimming or diving in summer, and they can oscillate slowly from time to time, as a result of wind, variations in atmospheric pressure etc.

Eddies: A twig blowing in the wind in a lake, stones sticking up out of a stream, the piers of a bridge in a river – the attentive observer will notice a series of eddies produced by all these obstacles. Whole strings of eddies are made visible on the surface by differently reflected light. But most of the eddies in water remain hidden. They are to be found in a large variety of unseen forms, in all waterways. It is not until traces of sand start drifting with the water, or colour is provided by clay or mica-schist, that all this diversity becomes visible.

Meanders: Even small watercourses, like melting glacier water, trails of water trickling over fields of sand below the tongue of a glacier in the mountains, shapes left behind by the falling tide on the beach or glacial valleys that have not been dammed show water’s natural tendency to meander.

These examples could continue. A great deal can be observed in nature, but she does impose limits. Random factors caused by a whole range of parameters and conditions that are often unfavourable to precise observation limit perception. And therefore some questions can only be investigated by experiment:

Experimenting in order to understand water

Even though flow movement in water does follow certain laws, about which we know a great deal today, the specific ways in which they develop are full of surprises. Experiments can be very simple. The more minimal their construction the more astonishing the results often are.

A smooth, water-resistant sheet, as polished as possible, made of something like glass, perspex or wood coated with plastic, is placed in a diagonal position. Water flows on to the highest point of the sheet from a small diameter hose. You expect a thread of water to trickle down in an absolutely straight line, following the shortest possible route according A smooth, water-resistant sheet, as polished as possible, made of something like glass, perspex or wood coated with plastic, is placed in a diagonal position. Water flows on to the highest point of the sheet from a small diameter hose. You expect a thread of water to trickle down in an absolutely straight line, following the shortest possible route according

| |

![]()

![]() To do justice to water we have to go into the waterworld ourselves, experiment with it and learn to think in an integrated and interdisciplinary way about its flow and flexibility.

To do justice to water we have to go into the waterworld ourselves, experiment with it and learn to think in an integrated and interdisciplinary way about its flow and flexibility.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()