In many urban locations and also in many other landscape situations as well, one is often required to work in a restricted space and to use this restricted space in a very effective way. It might be a green string in-between a housing area and a traffic road, it might be a green isolated pocket in a sub-urban environment, or it might be in-between two agricultural fields. Many questions are raised in dealing with such very small plantations. When do the interior rooms and the interior woodland habitats occur? When can you start to differentiate between outer and inner edge zones? When does it become a wood as opposed to a shelter belt? How can woodland perennials survive in the long term? At what size can we start to talk about long-term sustainable systems? Such, and similar, questions have not been discussed enough, but they are as

|

|

7.8

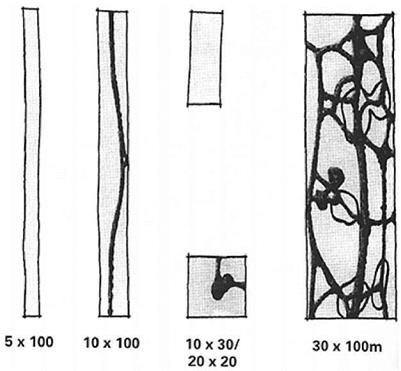

Possible paths in woodland belts of different dimensions give rise to different possibilities for path networks, nodes and glades.

Dimensions in metres

important as it is for a football team to have a pitch of a certain size in order to be able to play football (Figures 7.8 and 7.9).

When do interior qualities develop in a piece of woodland? This is a question focusing on critical minimum sizes. The ability of plants to survive or to grow well is related to size. In small plantations the chance is reduced, especially in a hard climate or with hyperactive wildlife. Also, human use is dependent on scale. Figure 7.8 shows the possibilities for paths in woodland belts of different widths. When does the first informal path start to occur? When do you also get a chance to create a parallel path? When do the children create a whole system of paths and somewhat enlarged ‘microrooms’? Empirical studies have shown that critical sizes are often found around widths of 10-12, 25-30 and 60-100 m. In practice, long, narrow

|

|

7.8 (a)

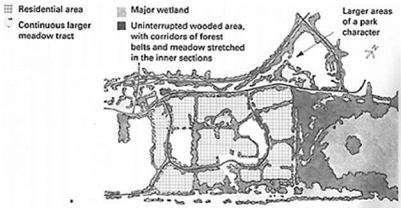

Oakwood, Warrington. The design concept for this British New Town was based on ‘nature fingers’ linking woodland blocks with residential areas

plantations are too often 2-4 m: too narrow to give the important ‘interior qualities’.

The quality, size and width of woodland belts in practice on a green structure level, in Oakwood, Warrington, UK, provides a contextual discussion (Figure 7.9(a)). Here a design concept was used in which ‘nature fingers’ are meant to meet ‘garden approaches’. Furthermore, the woodland belts were meant to play an important mental role in separating and cutting down the size of housing areas to a human scale, and underlining a landscape identity to enable an understanding that you are living in front of, or behind, the woodland belt in question. The woodland belts also function as part of an overall green network, creating the necessary ‘good’ contact with parks and natural areas in the outer zones. But the questions should be taken deeper: what does the choice of different widths mean in practice, for human appreciation, for children’s play or for the plants and their growing conditions? (Tregay and Gustavsson 1983).

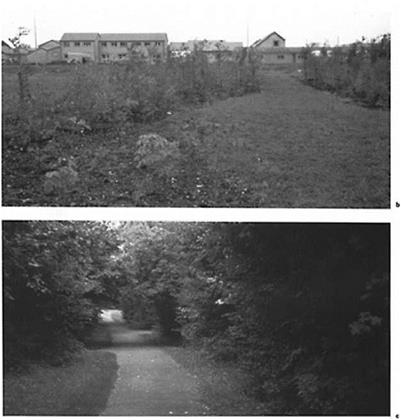

Figures 7.9(b) and (c) show photographs from a woodland belt in Oakwood over a period of 20 years. Ecologically, many of the woodland perennials have started to form viable carpets, and there is a high amount of flexibility when undertaking coppice – inspired management, keeping a good balance between light and shadow. The location of the walk road is problematic, by creating an experience of being outside and not really belonging to the interior world if the coppice is used with too short intervals or is too mechanically focused on the road-verge zones. The use of ‘rough’ plants, especially nettles, is also problematic, considerably reducing the feeling of a woodland character.

|

|

7.9 (b) and (c)

Woodland belt in Oakwood, Warrington (b) 1978, shortly after planting. (c) 20 years later