After the death of Rikyu in the late sixteenth century, the emergence of the sukiya-zukuri architectural style led to a new shoin + sukiya + soan arrangement, which combined buildings and gardens of these three styles into a single linked structure.

Positioned between the large, magnificent shoin, with its formalized decorative accoutrements denoting high status, and the tiny, rustic soan hut which was considered “uncomfortable for guests,” was the semi-formal sukiya, also known as the sukiya shoin. Characteristics of sukiya – zukuri include the use of columns with unbeveled corners (menkawabashira), earthen walls (tsuchikabe), and understated, delicate decoration.

The method used to link these three completely distinct interior spaces and their respective gardens into one continuous building-and-garden form, while barring the view from one to another, was miegakure. And the architectural composition used to effect this was the diagonally-stepped “geese-in-flight” formation (gankokei) that had been used earlier in asymmetrical shinden-zukuri mansions (Figure 42).

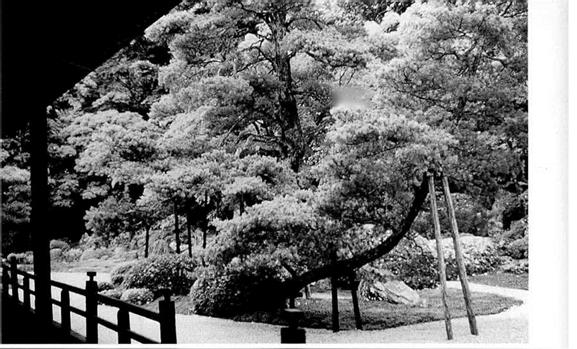

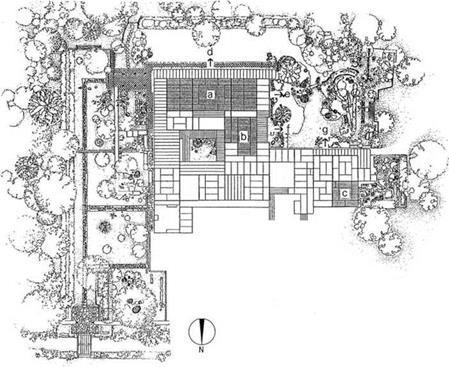

Manshu-in is a sukiya-zukuri temple in northeast Kyoto, composed of two shoin—one in the formal shoin style, and the other in the sukiya style—and a soan-style tearoom (Figure 43.1-43.5). The garden, as viewed from the jodan (higher level) of the formal shoin, likewise has a formal, highly refined composition centered on a main feature—a single “boat” pine (funamatsu).

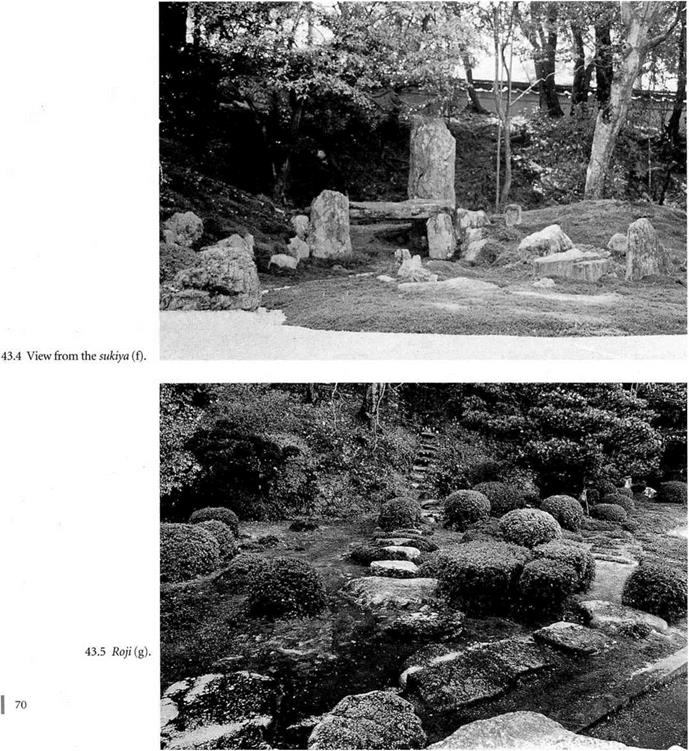

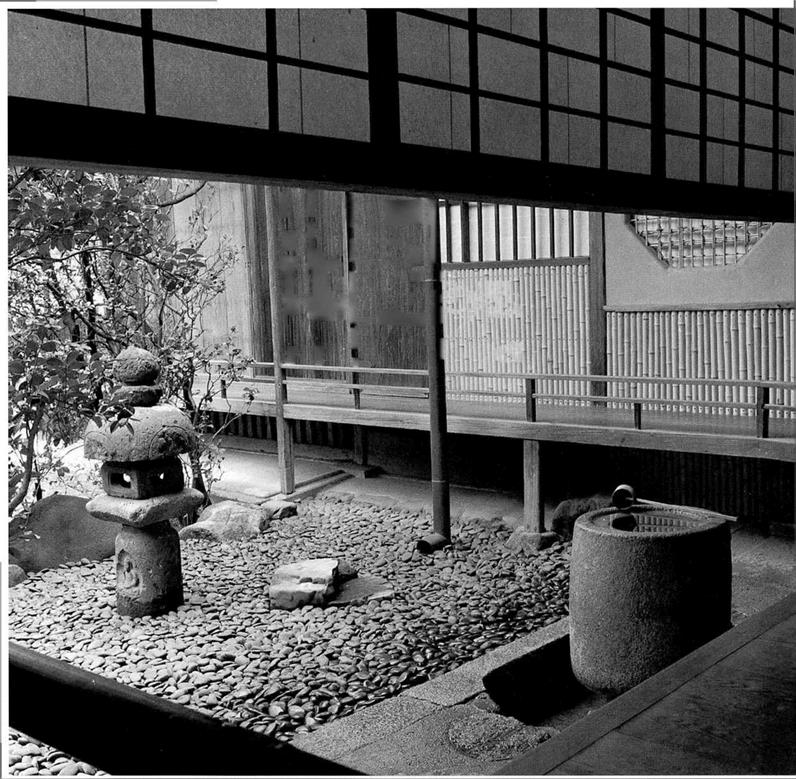

The recessed sukiya shoin is accessed by an external corridor that extends from the veranda of the formal shoin in a “zigzagged” form, linking the two buildings. From this veranda, the view of both shoin is partially obscured by two trees placed so as to interrupt the lines of sight from one building to another. The main scene in the dry waterfall garden, a Buddhist triad rock (sanzonseki) arrangement, corresponds to the view from the sukiya shoin (composed of an anteroom called Fuji no ma and a main room named Tasogare no ma).

A dynamic stream of white sand representing the ocean links the two heterogeneous views—that of the representational boat pine garden corresponding to the formal shoin and that of the abstract dry landscape waterfall garden relating to the sukiya. Tucked into the garden recess formed by these two buildings, a lone island floats in the ocean, hosting the single pine that is the central focus of the overall garden composition and that effects the miegakure linking the qualitatively distinct shoin and sukiya.

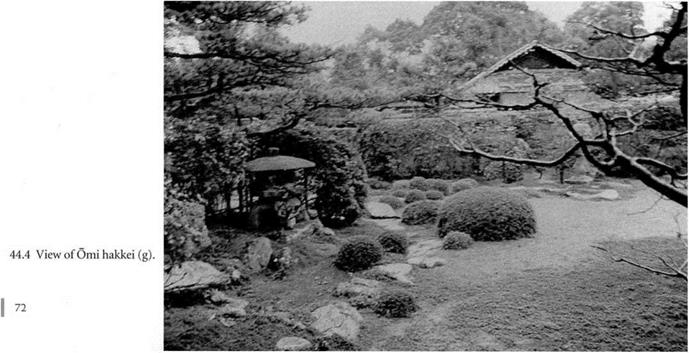

A series of stepping-stones extending toward the adjacent mountain then marks the boundary between the qualitatively distinct areas of the sukiya and soan and their respective dry waterfall and roji gardens.

The side wall of the Tasogare no ma affords a view of the simple roji garden, composed of stepping-stones, laid under the eaves, that lead off to the Hassoseki (Eight- window tearoom).

Just as the shoin, sukiya, and soan structures are combined in the geese-in-flight formation, so are their respective shin (formal), gyd (semiformal), and so (informal) “sub-”gardens structured by means of miegakure into a marvelously integrated, total garden composition.

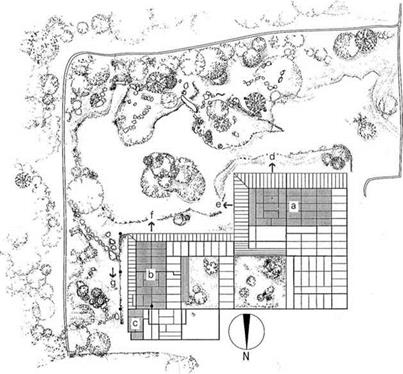

43.1  Plan view drawing of Manshu-in.

Plan view drawing of Manshu-in.

a. shoin.

b. sukiya.

c. soan.

d. formal garden.

e. “linkage.”

f. semiformal garden.

g. informal garden.

|

![]()

|

|

|

|

ii Й I І і 1 і 1 II І |i ifv |

1 Шві 1 1 . – I1J. с . я І, і. Р • 1 Б ; Ш Я |

|

|

І І і ІІ’ЖТ |

І ^ І ■ ■ . t • І і і |

f”’ illllnilililllu Hiimilllll і’тІЇ |

|

’HI f. І |

1 Л Шж 1 і В. |

1 і J І • : І П I ill і |

|

‘Ці: Щ:’ , JE Щ |

і! |

1 iJlffl |

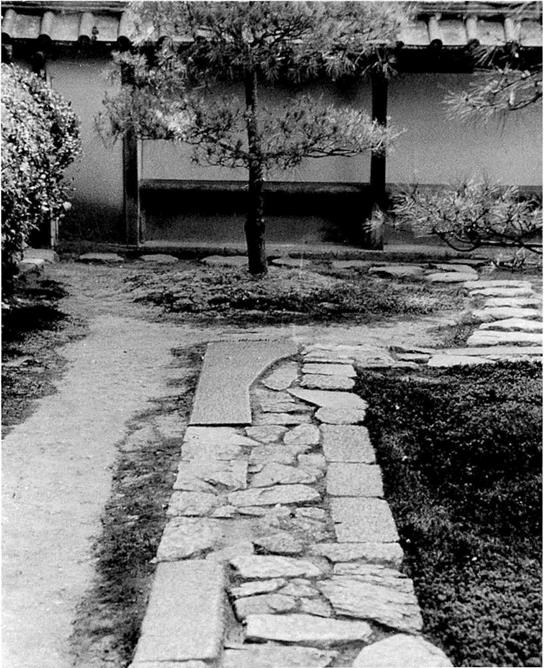

44.1 Daitokuji Koho-an roji to the Bosen tearoom, Kyoto.

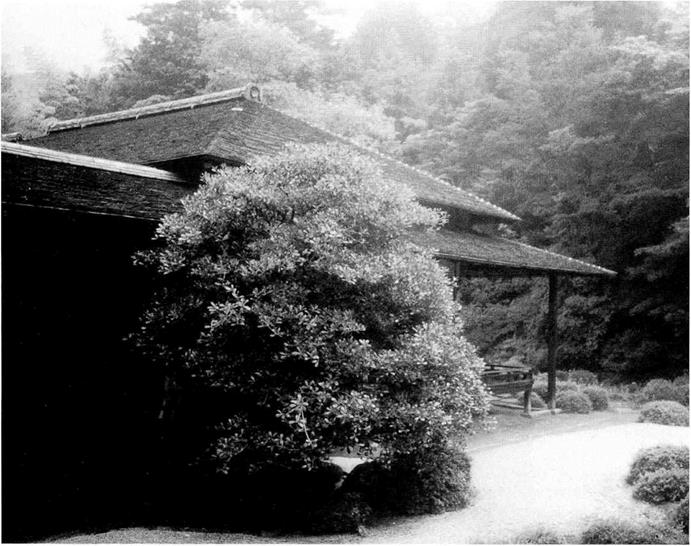

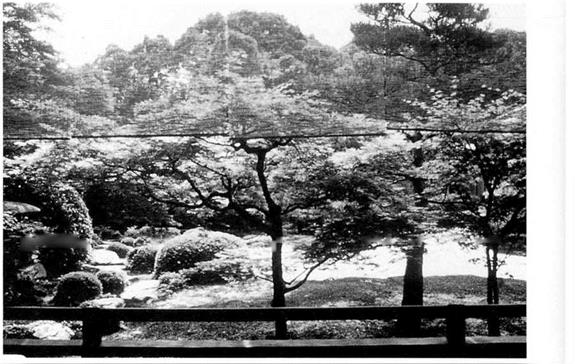

The compositional structure of buildings and gardens of Koho-an at Daitokuji in Kyoto is similar to that of Manshu-in. The hojo, Bosen tearoom, sukiya, and San’unsho tearoom are linked—with their respective gardens—in the geese-in-flight formation. The garden is a combination of the hojo’s “empty” garden, defined by a double-tiered hedge, and a vast, oceanlike, light-bathed garden called Omi hak – kei (literally, “eight sights of Omi”; Figures 44.1-44.5).

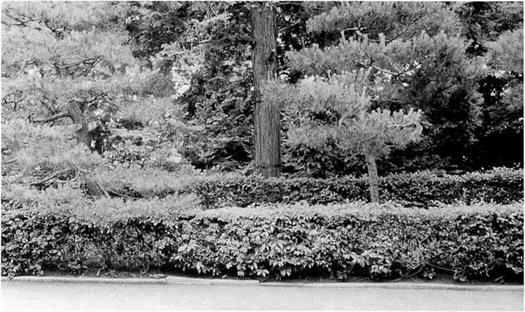

The composition of the Koho-an garden is marked by the arrangement of some dense and some sparse clusters

of trees close to the eaves, designed to conceal and reveal by turns the “oceanic” garden beyond. Thus, a full view of the Omi hakkei is not visible except from the veranda of the sukiya. The garden’s rather vague, “watery” composition may be more easily understood as a backdrop against which the foreground shrubbery is highlighted and silhouetted when viewed from the interior of the Bosen tearoom; its role is similar to that of gold-leaf grounds in wall paintings of the Kano school.

As the viewer moves from the hojo, glimpses of the

44.2

View from the hdjd (d).

View from the hdjd (d).

|

44.5 Plan view drawing of Daitokuji Koho-an.

44.5 Plan view drawing of Daitokuji Koho-an.

a. ho jo.

b. Bosen tearoom.

c. San’unsho tearoom.

d. hdjo garden.

e. “linkage.”

f. roji.

g. Omi hakkei.

|

![]()

bright Omi hakkei garden are provided through the spaces between the trees, which become incrementally smaller—from one to one-half, and finally to one-fourth —until the row of trees ends at the entrance to the Bosen. Together with dense shrubbery that obstructs a full view of the garden, a shoji screen spanning the upper half of Bosen’s exterior “wall” also blocks the line of sight, while the open lower half allows a suggestion of the Omi hakkei to linger and at the same leads the eye into the tearoom. Stepping-stones set in miwado cement in the space between the eaves and the row of trees forms the roji between the hojo and Bosen. The open-walled entrance beneath the half-shoji is a new and original form of nijiriguchi (low entranceway to the tearoom), called the funa-iri, or “boatmooring” style.

While Manshu-in constitutes a basic form of miegakure configuration, here we see that same methodology perfected through the superb technical skill and acute sense of modeling of architect, garden designer, and tea master Kobori Enshti. The master’s distinctive modeling can also be seen in the composition of the approach to Koho-an.

First, the stone-lined moat defining the boundary of the subtemple grounds is unique and innovative. The thick, comb-shaped stone bridge spanning this moat is ingenious, as are its central beam, its columns, and the brace stones securing it at both ends. A stretch of stone pavement set in the middle of a bed of cryptomeria moss forms one straight line running between this stone bridge and the outer gate and extending to the waiting bench at the far end of the approach.

On the same axis, just in front of the waiting bench, there is a single “interrupting” tree, around which the stepping-stones arc in a semicircle. The roughhewn stonework in this stretch of pavement is state-of-the-art. A large single stone forms the outer corner of the bend in the path directly in front of the waiting area. Its very form “points” to the right, and so skillfully leads people around the turn to the entrance hall (Figure 44.6). Miegakure effected by an interrupting tree that blocks an axial view is a device also utilized throughout the garden of Katsura Rikyu.

The idea of aligning the entrance gate and the waiting area on the same axis, with a single tree interrupting the long sight line, would be unthinkable in roji composition; this gives some indication of the originality and freshness of Enshu’s insight.

The experience of walking through an environment composed of combined shion, sukiya, and soan buildings and gardens, such as those of Manshu-in and Koho-an, is very different from that of walking a roji. These combination shoin/sukiya/soan gardens were designed to be viewed primarily while walking within the building confines and represent a development of the technique used to link views of similar quality that was seen earlier in Zen temple north gardens. In sukiya-zukuri environments, however, we see the linking of scenes of completely different qualities. When the “walk through the garden” was separated and made independent of the building, the technique of linking heterogeneous garden forms with miegakure developed a step further, culminating in the Edo-period stroll garden.