Shinden-zukuri gardens, which were integrally linked to the structure and composition of the corresponding architecture, developed with as much variety as did palatial buildings in the same style. Like palace architecture, gardens too had requisite prototypes. The opening line of Sakuteiki in fact refers to the inextricable correlation between prototype and interpretation:

In making the garden, you should first understand the overall principles.15

Sakuteiki then outlines three overall principles which together form the prototype for all garden making, and which epitomize all the garden styles described later in the document.

1. According to the lay of the land, and depending upon the aspect of the water landscape, you should design each part of the garden tastefully, recalling your memories of how nature presented itself for each feature.16

This first principle cites “the natural landscape” as one of the prototypes for garden making. Design is governed by site conditions and must respect and highlight the natural features of a location. This guideline instructs the designer to recall his own direct experiences and observations of nature, and to use them in interpreting the prototype. A similar line appearing later in the text—“the stones placed and the sceneries made by man can never excel the landscape in nature”—reinforces this principle.17

2. Study the examples of works left by the past masters and, considering the desires of the owner of the garden, you should create a work of your own by exercising your tasteful senses.18

The second principle designates “works left by the past masters” as prototypes, and urges caution in the exercise of creative impulses. This focus on masterful work helped to ensure the continuation of tradition and was an important factor in turning garden masterpieces into prototypes themselves.

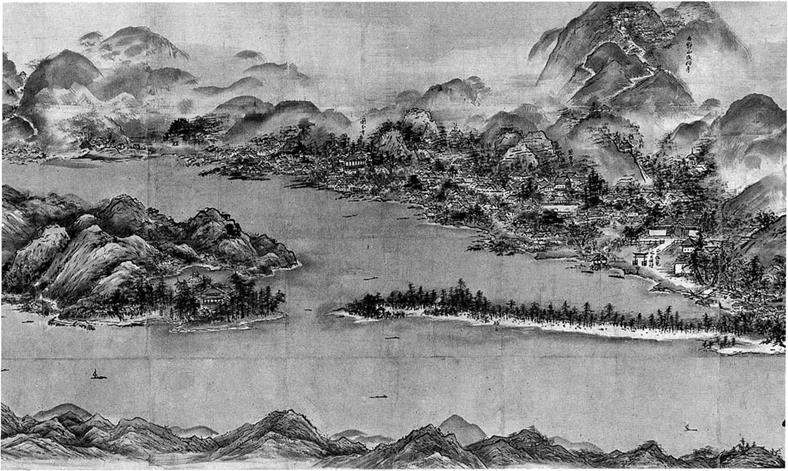

Descriptions of early Japanese gardens—such as Soga Umako’s “Shima no Oomi no niwa” in the historical chronicle Nihon shoki (comprising thirty volumes, compiled in the seventh and eighth centuries), and Prince Kusakabe’s “Tachibanajima no Miya no niwa” in Manydshu (the seventh – and eighth-century collection of Japanese poetry)— along with vestiges of the gardens of Heijo-kyo excavated in 1975, suggest that all were natural landscape-style gardens. During the mid – through the late Heian period, when Sakuteiki author Toshitsuna was active, the development of the shinden-zukuri garden had nearly reached maturity. Surrounded by mountains on three sides, the Kyoto basin’s natural environment supplied an abundance of the finest varieties of garden materials—rocks, plants, sand, clear streams and natural springs—and was as beautiful as it was rich in resources. Heian-period gardens making ingenious use of the terrain developed as an extension of the natural landscape-style gardens of the Nara period. Today the only remaining natural spring-fed ponds that reflect Heian-period methods are those of the former emperors’ villas, Shinsen’en and Saga Betsu-in. Both are traditional natural landscape-style gardens with nature itself as their prototype.

Since the shinden-zukuri garden was designed primarily for viewing from inside the palace, the “owner’s tastes” as reflected in the room interior would necessarily have had a strong impact on people’s perceptions of the garden. Thus “considering the desires of the owner of the garden” was fundamental, and served as the basis upon which the designer should finally “create a work of his own,” or bring into play his own creativity and subjective judgment.

3. Think over the famous places of scenic beauty throughout the land, and by making your own that which appeals to you most, design your garden with the mood of harmony, modelling it after the general air of such places.19

The third principle specifies “famous places of scenic beauty” as a prototype, which relates to the thematic subjects of gardens.

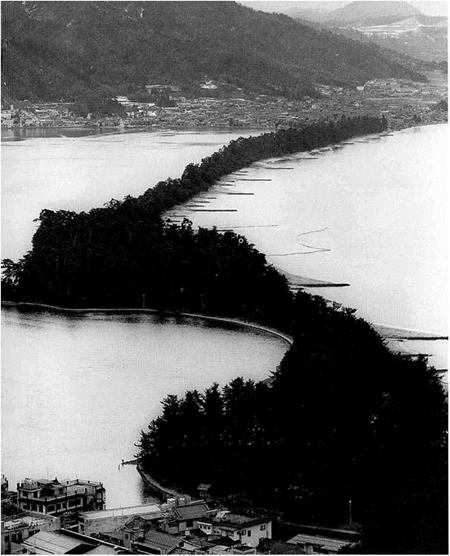

Poetry pervaded all aspects of Heian court life and gardens too bore evidence of literary influence. Gardens were one means of displaying miyabi—court elegance and refined aesthetic taste—and served as the setting for formal poetry composition matches. As such, the garden itself should be a “poetic” expression as well as a source of poetic inspiration. As a theme, “the natural landscape” was too broad a topic to express succinctly, and so articulating it metaphorically, in the form of commonly understood poetic images, made it easier for the viewer to grasp and for the designer to narrow down the focus of his expression. Thematically, famous places of scenic beauty such as Wakaura, Suma, Akashi, Amanohashidate, and Shiogama carried specific literary connotations; simply

|

|

|

|

alluding to these places evoked particular phrases, moods, or images. “Famous places of scenic beauty” were extracted from the prototype of “the natural landscape.” At this point in Japanese garden history, the recreation of famous sights had been established as an appropriate metaphor for “the natural landscape”; it has maintained this same status through the present day (Figures 9.1-9.3).

An excerpt from Jikkinsho (also known as Jikkunsho), a Kamakura-period collection of tales based on stories dating from the Heian period, describes one such Heian garden recreation of the famous pine tree-covered sandbar called Amanohashidate (literally, “bridge of heaven”), located on Tango Peninsula in the Japan Sea:

At the southeast corner of Nanajo and Muromachi is the one-cho Sukechika residence. Modeled after Amanohashidate in Tango, the island in the center of the pond is elongated and planted with young pines.

The three overall principles in the opening paragraphs of Sakuteiki are related to the famous Chinese treatise on art that transcends formal representation—Xie He’s Six Laws

(liu-fa) of painting. First defined in the preface to his Gw hua-pin-lu, or Classification of painters (ca. 535), they were continually referred to by Chinese theorists thereafter, and are debated by scholars worldwide to this day.

Long ago Xie He said that painting has Six Elements [or Laws]. The first is called “engender [a sense of] movement [through] spirit consonance.” The second is called “use the brush [with] the ‘bone method.’” The third is called “responding to things, image [depict] their forms.” The fourth is called “according [adapting?] to kind, set forth [describe] colors [appearances].” The fifth is called “dividing and planning, positioning and arranging.” The sixth is called “transmitting and conveying [earlier models, through] copying and transcribing.”20

The second half of Sakuteikfs third general principle— “by making your own that which appeals to you most, design your garden with the mood of harmony, modelling after the general air of such places”—is analogous to Xie He’s second law. The “bone method” is the “depic

tion of a likeness, while respecting bone spirit”; in other words, it requires seeing through to the skeletal structure, or the very essence of a subject. It is a process of extracting the most characteristic forms and eliminating anything superfluous. The “mood of harmony” mentioned in Sakuteiki’s third principle is akin to the process of “depicting” or “describing” the extracted abstract form which is the subject of Xie He’s third and fourth laws. Further, Toshitsuna’s injunction to “study the examples of works left by past masters” is equivalent to Xie He’s sixth law, on “copying and transcribing.”

The prototype outlined in Sakuteiki s three general principles calls not for a faithful, realistic portrayal of nature, but an evocation of its spirit. That which was acquired by studying nature was to be conveyed figuratively—with for instance a depiction of Amanohashidate. Portraying intrinsic quality has been the most fundamental point in Japanese garden design throughout the ages. By changing the degree and style of “description” added, the Japanese garden developed into the abstract gardens of the Muromachi period (1333-1568) on the one hand, and the condensed gardens of the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568-1603) on the other. Japanese abstract (Zen) gardens and representational (shoin-zukuri) gardens are not at all antithetical styles, since the point of departure for both is “modelling after the general air of such places.”