As we have seen, the composition of residences in Choson Korea was directly influenced by Chinese Confucianist political thought, and we can safely conclude that the kind of garden often depicted in Chinese landscape paintings and based in the tradition of retirement from society, was not part of the yangban domestic environment. The only similar garden in the Korean tradition to these Chinese gardens was the pyobo environments surrounding the hermitages of the

Confucian scholars who lived in the mountains and forests.

Confucian scholars were men whose profession it was to read books. One fundamental precept of neo-Confucianism was that a person could achieve a higher level of virtue through reading and could thereby qualify for a role in government. Such study was an absolute prerequisite for all government officials. Since neo-Confucian thought held character and virtue in higher esteem than any other qualities, some individual yangban living in the provinces who already enjoyed a tranquil, untroubled existence eschewed official rank completely and devoted their lives to study. These men were highly respected in traditional Korean society, and were renowned as ilmin, or “hermit scholars.”

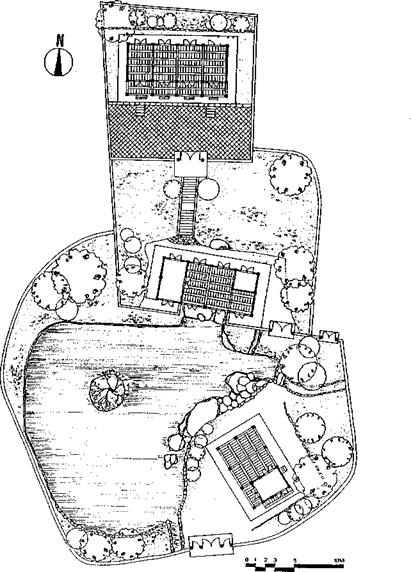

Ilmin hermit scholars built places of retreat at locations of exceptional natural beauty, far from the villages where their families and neighbors lived, and operated schools called chdngsa, which offered the only form of education available other than the sowon national system attended by children of the upper classes. These schools were usually named after the locale, some particular characteristic of the local scenery, or even the pen name of the teacher himself. The chdngsa played an important role, alongside the sowon, in Confucianism’s spread among the common people and its establishment as the national religion of Korea (Figure 120).

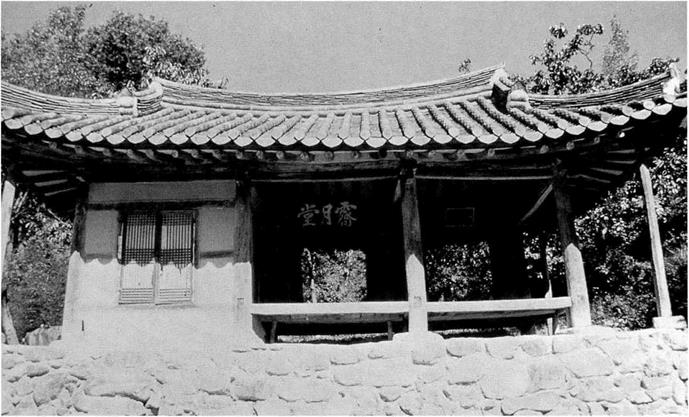

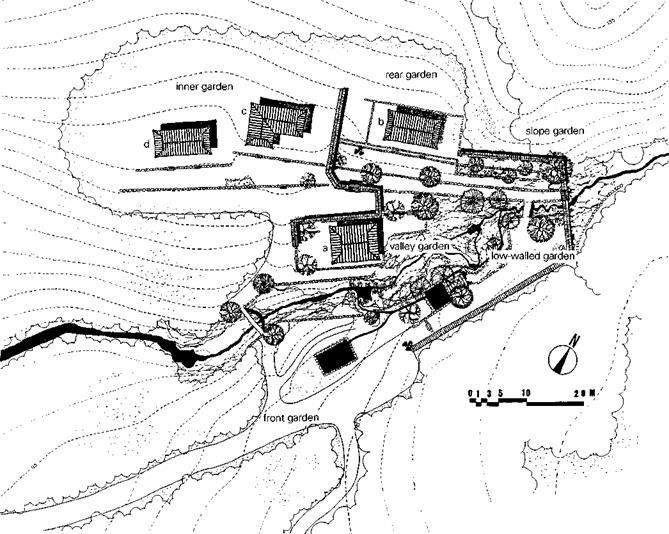

If the hermitage and chdngsa were a form of inner garden, the surrounding natural environment was the outer garden. “Pyolsd” was used to denote the environments created by ilmin hermit scholars through the construction of belvederes, halls and pavilions amid valleys, waterfalls, springs, and artificial hills which were ensconced in nature. The composition of this natural scenery was based on concepts and methods that are free and uninhibited, which would never be found in the grounds of a yangban mansion, yet are just as much an integral part of Korean gardening tradition. Soswaewon is a prime example of this garden style (Figures 121.1-121.6).

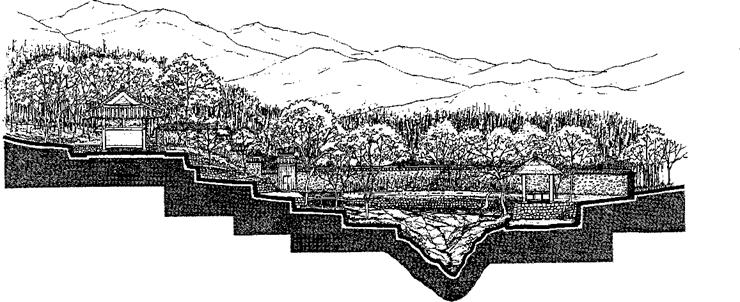

Soswaewon is a garden of approximately 5,000 square meters (1.25 acres) set deep among the mountains of South Cholla Province. It was the pyolsd garden belonging to a great noble in the mid-Choson period (around a. d. 1530), and has recently been restored by the Office of Cultural Properties.

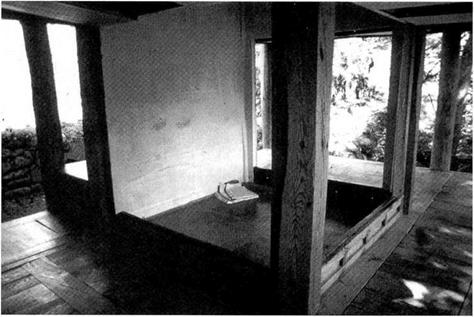

A nearby valley with its fast-running stream and surrounding mountains were skillfully utilized to create this beautiful garden. The front garden (or approach), the low-walled garden, and the slope garden, all of which overlook the central valley garden, are circled to reach the Chewoldang. This hall stands on a high point affording a view of the entire garden and consists of a single ondol – heated room (pang) of one k’an and a wooden-floored room (таги) of two kan, which has a rear garden. Behind a stone wall set back from the far side of the Chewoldang are the gardens of the Koam chdngsa and Puhwondang, which have not yet been restored.

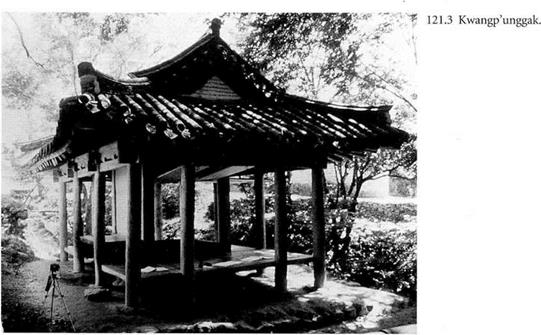

An earthen bridge crosses the lower end of the valley stream and leads from the approach directly to the inner gardens. The valley garden is located at the heart of Soswaewon and features a single building, the Kwang – p’unggak, a pavilion consisting of an ondol-heated room of one k’an surrounded on all sides by wooden-floored rooms. This open-sided pavilion looks out over the fastrunning stream and a waterfall.

Soswaewon’s composition is expressive of retirement and seclusion—the very same realm as is expressed in the landscape painting traditions in which poetry and painting are regarded as one. Pyolsd garden composition involves concepts not applied to any garden of the yangban estate, even in a more artificial or stylized form. These pyolsd gardens evoke, rather, forms predicated on the philosophy behind Chinese yuanlin.

Yet there are fundamental differences in Chinese and Korean thought about the design of their respective gardens. P’ungsu, or feng shui, is the art of divining features

|

|

|

120 Section and site plan views of the Namgan chongsa. |

|

|

associated with good and bad fortune in any site— whether for a city, a village, a single home, or a grave. This point is common to both China and Korea, but whereas the Chinese set about to construct landscapes which would fulfill the conditions for good feng shui, Koreans selected sites whose natural characteristics already met those same requirements and therefore needed no modification.

The Forbidden City in Beijing was built on a broad plain, which meant that the “mountain behind, river in front” condition for favorable feng shui needed to be created artificially, and thus a man-made mountain was erected as backdrop to the palace buildings and an artificial river, the Jin-shui Channel, was dug to the south of the complex. The site of Kyongbokkung in Seoul was selected because it was myongdang, or choice land—overlooking the wide Han River to the south, and with Mount Pukak standing behind it to the north.

As we have seen, the Chinese garden treatise Yuan ye defines the primary method of site preparation as yin-di zhi-xuan, or accentuation of the natural lay of the land by raising high points and deepening low points. By contrast, the selection of a site that offered all the requisite natural features was foremost in Korea. The reason for this difference in approach lies in the two countries’ differing

topographies. Whereas the two regions central to Chinese culture under the Ming and Qing dynasties—the political and administrative center around Beijing and the com – mercial/economic center of Jiangnan—were both flat, broad plains, Korea is a land of undulating hills and mountains. These geographical factors seem to have helped shape the divergent senses of beauty in the two cultures.

Although the composition of traditional dwellings in China and Korea alike was based on the principles of Confucianism, garden styles in the two countries differed. In China, gardens were symbols of the elite, independent from but contiguous to dwellings, and reminiscent of the Chinese shanshui landscape paintings that gave visual form to the precepts of Taoism. In Korea, gardens were incorporated into the residence in accordance with the Confucian sense of order, and any Taoist expression was effected within the highly natural environment of the hermit scholar’s pyolsd. These differences also stem from the fact that the concept of retirement in Ming – and Qing – dynasty China—where retired officials could return to their posts—became largely symbolic and lost much of its true meaning. The seclusion of Korea’s ilmin hermit scholars was permanent. The ilmin gained the respect of the common people by renouncing the mundane world and any chance of one day returning to it. Nevertheless,

|

|

|

|

the prototype for each was the expression of the concept of retirement as embodied in Chinese landscape paintings and landscape painting theory in which poetry and painting were perceived as one.