It is precisely these questions that we sought to answer in the Yard to Garden intervention project at the Child Development Laboratory at Iowa State University. This project involved child development specialists from the laboratory who collaborated with me to design landscape situations that would fulfil specific developmental milestones of the children (two to six years old) attending the

laboratory school. A significant difference between Yard to Garden and the Infant Garden, was the ‘intervention’ nature of the installation. Unlike the complete redesign of the play space at the Infant Garden, the Yard to Garden research project involved the placement of temporary and permanent landscape elements in the existing play yards of the laboratory. This entailed 23 permanent plant installations, stonework, boulders, and temporary play props such as wind chimes and giant ice blocks. This method of installation was significantly less expensive than the total redesign of the Infant Garden. Hence, we attempted to mimic what a daycare facility or school might actually be able to afford and execute. It also allowed us to assess the effects that the interventions had on the use of the existing play structures.

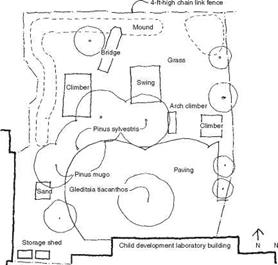

We hypothesized that the introduction of natural material into the existing yards would offer additional types of developmental opportunities to the children. The existing yards of the school contained several play structures, grass, trees, and an enclosing chain link fence. Observation of the children using the yards demonstrated to us that the play equipment did foster physical

|

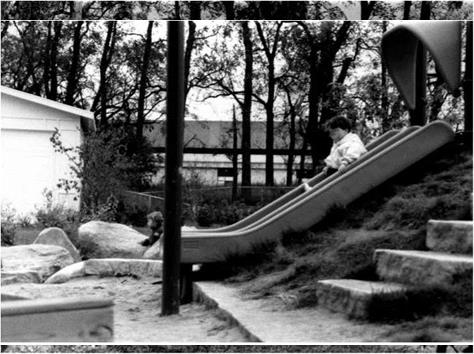

Figure 11.6a Previous preschool yard at Iowa State. |

development. Physical competence was gained as the equipment was used and abused by children. The play structures were gravitational forces in the yard for the children as they were sites where children gathered to socialize. Consequently, the physical prowess of a child established his or her order in the social hierarchy of the class. The child who could climb the highest and the fastest was the leader. Some children, many of them kindergarten girls, who were not drawn to the play equipment, did not venture into the yard at all, but stood against the school wall to socialize.

The hypothesis of this research contended that interventions of temporary and permanent landscape elements would offer different and more varied types of developmental opportunities than those provided through the existing yards. We compared children playing in the existing yards that contained primarily equipment and a chain link fence with the same children playing in the same yard with the interventions. The interventions are as follows:

Permanent interventions: [10]

|

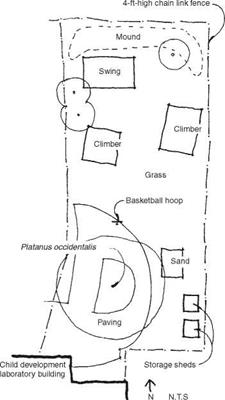

|

Figure 11.6b

Previous kindergarten yard at Iowa State.

4 Plantings in the asphalt area.

5 Unmown grass area.

6 Stepping stones.

7 Boulders.

8 Two vegetative rooms. Two 1.5 m X 1.5 m plant enclosures of Euonymus alata and Thuja occidentalis were installed in an open grassy area of the kindergarten yard.

Temporary interventions:

1 Ice blocks.

2 Wind chimes.

3 Overhead canopy.

4 Water troughs.

5 Movement of playhouse.

6 Sand buckets.

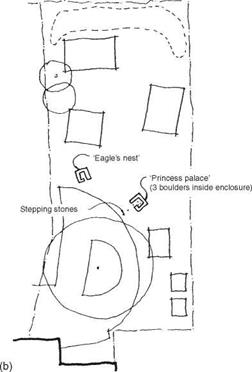

The results suggested that when simple landscape elements were introduced into these yards,

|

|

different types of development were encouraged.8 For example, we found that the vegetative rooms referred to in Figure 11.7b above inspired a wide range of fantasy play that was not witnessed prior to their installation. The use of these vegetative rooms changed the existing social hierarchy of the class because some children were more attracted to the rooms, and unlike the play structures these spaces became sites for fantasy play and socialization. Children tended to use these rooms more frequently and for longer durations than the equipment. The social hierarchy in the vegetative rooms was based on a child’s command of language and the imagination that he or she brought to that space. The child who could be the most creative and inventive was the leader. Hence, the social hierarchy of the play yard was now linked to the cognitive and emotional prowess of the children. The children who were dominant in the play structure social setting were not always the dominant children in the vegetative rooms. These

soft ‘living’ rooms and many of the other plants also accentuated the seasonal changes taking place in the outdoor play space, and encouraged children to observe their environment more closely. For example, the leaves of the Euonymus alata shrub turn brilliant red in autumn and the children noticed this as well as their unusual winged branches.

Other examples are the stepping stone pathway and boulders. As part of the intervention project, we imbedded approximately twenty stepping stones, evenly spaced apart, into the play yard. The stepping stones travelled in a meandering path from the school’s exit door to the yard, to the major play equipment structures, and through a part of the yard that was not usually used by the children. We found that children followed these stepping stones, and they began to play in previously under-used parts of the yard. We don’t typically think of children following paths; however, paths are landscape elements that help structure our

|

understanding of the environment. When travelled upon, they are both a physical experience and a cognitive measurement of the space. We also placed approximately four boulders throughout the yard thinking that they would be climbed on or serve as markers in outdoor games of tag. However, much to our surprise, the children began moving the boulders. This task often took two or three children, and this activity provoked planning, cooperation and coordination. Another dimension of boulder moving was that the children became keenly aware of the other children using the yard. During our study, two different groups (morning and afternoon) used the yard. Typically, toys and other items used by the previous group were put away at the end of their playtime in the yard; however, the staff didn’t move the heavy boulders. As a result, the morning group would move a boulder to a certain place in the yard, and then the

afternoon group would move it somewhere else. The boulders became memory markers between the children in the different groups.

This project provided tremendous insight into how designers and people who work with children can fine-tune the design of existing outdoor play spaces to match the specific developmental goals of their programmes. It also illustrated how the detailed nuances of the outdoor play environment matter in the daily life of children. Unlike the Yard to Garden project which intervened on an existing play yard or the Infant Garden project that involved the total redesign of an existing play yard, there may also be opportunities where the school or childcare centre and its accompanying outdoor play space is an entirely new construction. This was the case at Bright Horizons childcare centre planned for eighty-six children ranging in age from infanthood to pre-teen, in Ames, Iowa.

|

Multi-tasking

The Bright Horizons childcare centre was developed as a prototype for four centres planned for property owned by Iowa State University. The centre included twelve infants, eighteen toddlers, twenty-four pre-schoolers and thirty school-aged children. The design of the exterior play spaces involved myself, architects and landscape architects of record, university students, child development specialists, and staff from the Iowa State

Department of Facilities Planning, and Planning and Design.

The project site was the southern slope of a grassy hillside, typical of the undulating landforms of a till plain landscape. The site also contained a substantial stand of mature trees, and an active drainage swale that cut diagonally across the slope. The initial design for the outdoor play space included an 8000 square feet play area off one exit door of the childcare building. This proposed play

space contained a small open grass area, a large multi-level play structure, rubber matting, and a four-foot-high chain link fence that enclosed the space. Our first impressions of this proposal noted that this design failed to take advantage of the existing site conditions; the trees, the slope, the swale, or the southeast exposure that would serve as an ideal setting for a garden.

Iowa State University landscape architecture students created models that re-envisioned the outdoor play area using the existing conditions of the site. Students were encouraged to refrain from relying on play structures for the sole content of play. When we reported back with our models to the designers of record and the university, we were informed that the student designs were too costly, and that they must adhere to the budget allocated to the play yard. This budget was itemized as ‘equipment’ and constituted less than 3 per cent of the overall budget. After further negotiation, we realized that we needed to consider the budget of the play yard as part of the construction for the entire building process, and not simply as a piece of equipment. Fortunately, the University Design and Planning staff worked with Child Care Resources to redistribute the yard as part of the drainage and grading plan, which was 24 per cent of the overall budget; thus folding the landscape design into the construction tasks.

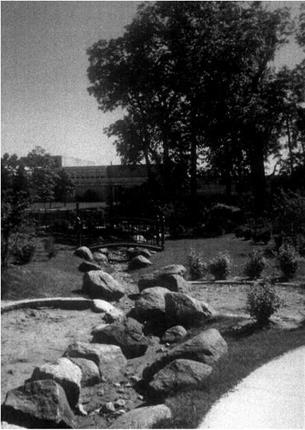

Hence, the yard emerged as part of the construction process. Numerous earthen mounds that helped to separate children’s diverse activities were made from the spoil piles created by the building excavation. The existing swale was preserved as part of the drainage system for the building run-off, and stones and trees that were removed during demolition were placed in the play yard for children to climb upon. ‘Landscaping plants’ that were originally planned in the front of the building for decorative purposes were placed within the children’s play areas at the rear of the building, and the equipment budget was used for small bridges that crossed the drainage swale and for moveable objects like sleds, bikes, wagons, and gardening tools.

The final design for the Bright Horizons play yard was organized into three exterior play spaces (the infant/toddler, the preschool and kindergarten, and

|

|

Figure П. П

Veterinary school childcare yard swale. (Photo: Susan Herrington.)

the school age space) which more than doubled the size of the previous proposal for the yard. Each age-specific yard was directly related to the use of the interior space of the building, so that the infant/ toddler room extended out to the infant/toddler yard, the preschool and kindergarten room extended out to the preschool yard, and the school age room extended out to the school age yard. Fieldstones from a local farm were placed throughout the site. Each yard contained these stones, some forming council rings while others were spread out to climb upon and view out from.

The exterior play spaces were separated by a forty-eight-inch-high fence, but gates were installed that allowed movement through each yard, and the drainage swale that took run-off from the building served as a unifying element that passed through all three play spaces. In the warm weather months this

|

|

swale is a place to dig and watch for bugs, in the rainy season it carries running water. During the winter months it is a snow-packed conduit for navigating through the play yard. The channel also reveals to the children that the play yard is not a

static picture of play outdoors, but an ephemeral event that is linked to the weather, natural processes, and human manipulation. Additionally, because the perimeter fence meandered into the established wooded area, this shady naturalistic

area where bugs could be caught and children could play became part of the yard.

While much of the work I’ve described deals with the small-scale nuances of a singular site, I wanted to know how the design of children’s outdoor play spaces might relate to larger environmental issues relative to planned communities. Could these children’s spaces that were becoming increasingly ‘green’ in my own work be valued not only by children, but by the entire community as an ecological resource? The following two projects, the Los Altos Schools and the 13-acres international design competition, have begun to answer these questions.