1.2.1 Furniture of Ancient Egypt

We mainly learn about the form and construction of furniture made in ancient Egypt from the perfectly preserved finds, reliefs and paintings that decorate the walls of the tombs of Pharaohs. It was found that many design solutions used by the contemporary artisans are also used today. All retained museum exhibits of furniture of ancient Egypt prove that the Egyptians used many techniques for decorating furniture. Gold plating and ivory incrustation were common methods of finishing the surfaces of furniture. These methods, as well as making legs in the shape of animal paws, became the common practice of carpenters from much later periods. To make valuable furniture, Egyptian carpenters used the wood of the ebony, cedar, yew, acacia, olive, oak, fig, lime and sycamore tree, often by importing this raw material from Asia Minor, Abyssinia or Namibia. Exterior elements of furniture were finished off not only with ebony wood combined with ivory, but also metal (brass, silver, gold), mother of pearl, lacquer, colourful faience and semi-precious stones (Gostwicka 1986). Ancient Egypt was familiar with bone glue, which was used in techniques of incrustation and veneering. The Egyptians used mortise and tenon joints and dowelled joints to combine most structural elements of furniture. In sarcophagi, chests and dressing tables they also used dovetail joints or bevelled joints (Setkowicz 1969).

|

Fig. 1.6 Bed of Queen Hetepheres IV, from the dynasty of Snefru, around 2575-2551 B. C. (reconstruction of the original from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) |

The oldest known Egyptian bed, more or less from the times of the first dynasty, is a design consisting of a horizontal wooden frame, resting on four thick and massive bull legs carved in ivory. The legs were joined to the frame usually with mortise and tenon joints, while on the frame of the bed, belts made from leather or other kind of plaiting were stretched over.

Beds with higher peaks on the side of the head were made with footrests. In some bed designs, the connection of the legs with the frame of the bed system was strengthened by bindings from leather strap stretched across drilled holes (Fig. 1.6). The beds in ancient Egypt did not have headrests, but wooden boards were placed at the side of the feet. The board was fixed by two bolts coated with a copper sheet, which also matched the sockets in the frame that were lined with copper. The board at the ends of the legs was the only ornate part of such a bed. The legs in the shape of lion paws were usually directed towards the head.

It is also known that the Egyptians used litters already during the first dynasty. The litter of Queen Hetepheres has survived to our times. Elements of the litter are also joined by leather straps or with a tongue and groove joint. On the front side of the seat back, at the height of the armrests, was an ebony strip inscribed by gold hieroglyphics.

Sitting furniture in Ancient Egypt had a wide variety of forms and an extremely large number of design varieties. A chair, table, bed and corner settee from the fourth dynasty (2600 B. C.), preserved in the tomb of Queen Hetepheres, had legs in the shape of animal paws usually turned to the front and always parallel to each other. They were not set directly on the ground, but on rounded bricks or spheres. If the armchair had a backboard and side rests, they were filled with papyrus, bas-relief or an openwork crate with figural, human and animal motifs, or symbols consisting of hieroglyphics.

|

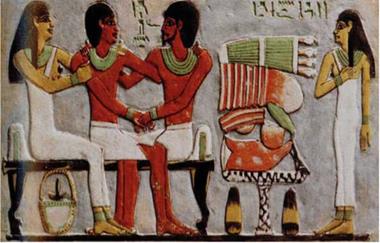

Fig. 1.7 Stela of Amenemhat, the end of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (middle of the second millennium B. C., Cairo Museum in Egypt) |

Figure 1.7 shows a limestone depicting a scene of a funeral banquet, in which the whole family participates. The father, mother and son named Intef sit on a long bench with legs in the shape of lion feet, with two low backboards on both its sides. Next to the bench is a lower, columnar table set with the sacrifice of various kinds of meat and vegetables.

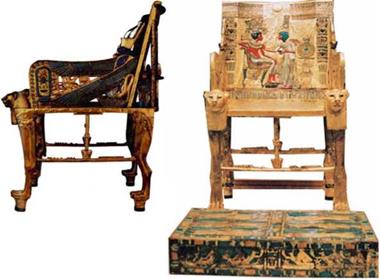

Tutankhamun’s throne is extremely impressive, richly decorated with gold, silver, semi-precious stones and a coloured glass paste (Fig. 1.8). Glass paste is a glassy mass consisting of silicates, fused in refractory forms, mixed with crystal and dyed with metal oxides. A special property of glass paste was its susceptibility to plastic working. The legs of the throne have the shape of lion paws, the armrests are two-winged cobras in double crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt, spreading the wings over the cartouches of the king. The front edge of the seat is decorated with two lion heads. The backrest’s decoration is a scene depicting Tutankhamun sitting on a soft upholstered throne with a pillow, holding one hand on the rest, and supporting his feet on a footrest. Ankhesenamun is standing in front of him and with his right hand he is rubbing Tutankhamun’s arm with an ointment from a dish in his left hand. This drawing illustrates that not only beds, but also seats and backrests of chairs were spread over with soft pillows filled with feathers or wool.

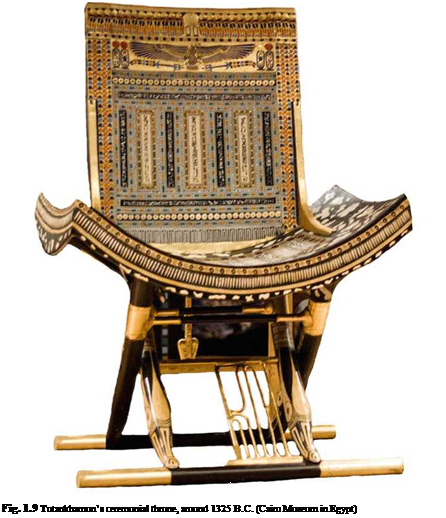

The folding chair found in the annex of Tutankhamun’ s tomb has a very interesting design, which was transformed from a stool by adding a backrest (Fig. 1.9). It is made from ebony wood with irregular incrustations of ivory, which imitate the skin of a leopard, while the legs have the shape of duck heads. The backrest is also made from ebony wood incrusted with ivory, decorated with semi-precious stones, glass paste and a gold sheet.

|

Fig. 1.8 Tutankhamun’s throne. West Thebes, Valley of Kings, Tutankhamun’s tomb, 18th dynasty, around 1325 B. C. (Cairo Museum in Egypt) |

When chairs appeared, the Egyptians also began to build tables. They were similar to each other in construction. The legs were usually made of thin stiles inclined at an angle to the ground and joined together in the central part with a connector, and in the upper part with a case. During funeral banquets, tables were erected on one, it seems, turned column (Fig. 1.10). This is an observation that is extremely intriguing, because so far traces of tools and equipment for turning, which the Egyptians could have used, have not been found. However, it seems highly unlikely that with such a developed technique, for those times, this technology was unknown to them. As reliefs show (Fig. 1.10), the seats of chairs were usually a bit higher than the working boards of tables, on which loaves of bread or incense burners lay.

Aside from chests for storing clothes, the ancient Egyptians made sarcophagi, coffins, dressing tables for storing toiletries and jewellery, as well as trunks. Many of them were made from wooden boards joined at the width, and in the corners dowelled, bevel and multi-dovetail joints were used.

The beautiful jewellery chest presented in Fig. 1.11 was found in the tomb of Yuya and Tjuyu. The chest is supported on long, slender legs adorned with a geometric ornament made from faience and ivory dyed pink. The same continuous pattern runs along the edge of the chest and its arc-shaped top. The sides are divided by a geometric frieze into two equal parts, the upper is adorned with a hieroglyphic inscription made in gilded wood, containing the cartouches of Amenhotep III and his wife Tiye, who was the daughter of Yuya and Tjuyu. The lower part is filled by a recurring motif consisting of symbols expressing the wish that the owner of the

|

chest enjoys life and fortune. The lid is decorated with two symmetrical panels of gilded wood and faience.