Southeast Virginia is the area bounded by the James River to the north, the Carolinas to the south, and the Piedmont to the west. Colonial furniture pro – duccd there is dramatic testimony to the combined influence of Williamsburg and Norfolk on rural cabinetmaking. Styles from these urban centers also extended into the Albemarle Sound and the Roanoke River Valley of North Carolina, and westward into the V irginia Piedmont.

The features found on furniture from this region that are characteristic of Norfolk include half-dustboards and inward flaring ogee feet. I low – ever, full dustboards and desk interiors of the Williamsburg type are also seen. Other parallels to Williamsburg are found in furniture from the Roanoke River region—particularly ease pieces w ith five feet, a characteristic that is associated with examples attributed to the shop of Peter Scott (figs. 39, 40).’

The features found on furniture from this region that are characteristic of Norfolk include half-dustboards and inward flaring ogee feet. I low – ever, full dustboards and desk interiors of the Williamsburg type are also seen. Other parallels to Williamsburg are found in furniture from the Roanoke River region—particularly ease pieces w ith five feet, a characteristic that is associated with examples attributed to the shop of Peter Scott (figs. 39, 40).’

Much of the furniture produced in southeast Virginia shows the influence of carpentry and house joinery, and indeed some artisans in the area arc – documented as having practiced these trades. Pieces made under such circumstances would naturally vary from the simple or coarse to the relatively fine and complex. Unlike more sophisticated examples of cabinetwork from Williamsburg and Norfolk, w hich show a strong reliance upon urban English style, this construction is representative of provincial Knglish furniture. Such construction was also widely used in New England, and it is possible that some of these techniques w ere introduced into Virginia from that area. Case pieces made under these conditions usually have exposed dovetail joints on the drawer blades. Dustboards usually were not used; instead, strips of wood were nailed to the insides of the cases to support the drawers. Bracket feet commonly have a single vertical block on their interior for support. Such construction methods are easier to execute than those employed in Norfolk and W illiamsburg, resulting not only in less expensive furniture but less durable pieces as well. The drawer blades w ith their exposed dovetails are prone to work their way out the front of the case, and the nailed drawer supports strain the case sides w hen they shrink, sometimes causing them to split.

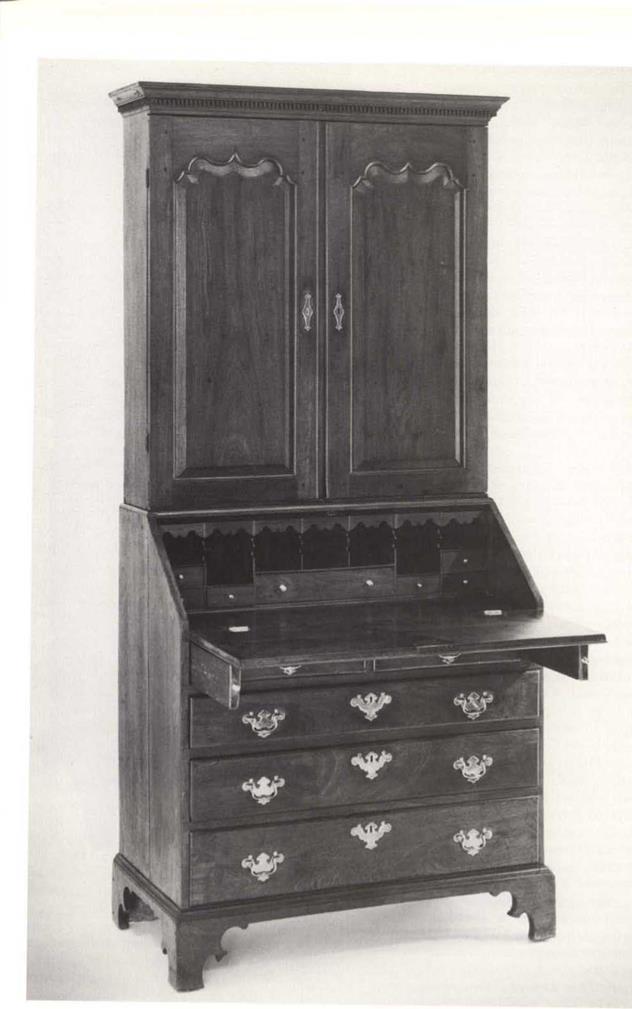

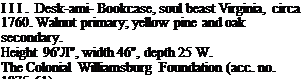

An early example of the combined influence of Norfolk and Williamsburg is found in a dcsk-and – bookcase with a history of ownership south of Petersburg (fig. III). The ogee feet are quite similar to those of the federal clothespress from Norfolk (fig. 109) and the dustboard construction is found on the examples signed by John Selden(figs. 105, 106). The triple inlays on the document drawers, the method of attaching the crown molding with large blocks, and

the wall-of-Troy molding are variations of details on a desk-and-bookcase attributed to Peter Scott (fig.

37) . The layout of the draw ers in the main case was also popular in Williamsburg (figs. 37, 75), but the drawer construction is an English type that is otherwise unknown in eastern Virginia, although it is found in Charleston, South Carolina. Each drawer bottom is made of two pieces that fit into a rabbet on the front and side and into a grooved batten that divides the drawer in the center.

One feature commonly found in southeast Virginia is the construction of the fallboard, which has a mitered batten attached with through tenons (tenons of this type are easily visible on the next desk, figure 112). The brasses are original, including the lattice-work escutcheons on the doors of the bookcase section.

Tw o inscriptions arc found on the top of the desk section: “Crawfords his desk,” appearing to be eighteenth century in origin, and “Jarrett,” which may refer to a town in Sussex County and probably dates from the nineteenth century. A simpler desk – and-bookcase now ow ned by Woodlawn Plantation in Alexandria has a related design and appears to be a product of the same shop. Many details of its design and construction are identical to those of figure 111.

|

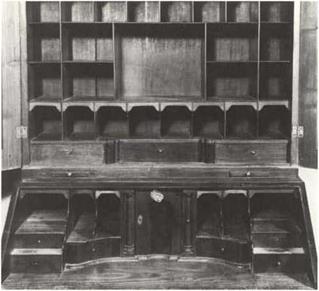

Ilia. |

One of the finest examples from southeast Virginia is a w alnut desk-and-bookcase that typifies the robust quality found in rural cabinetmaking (fig. 112). Purchased in Petersburg, it contains the inscription “Comans Well,” placing it in Sussex County in the early and mid nineteenth century. Even though it has a pleasing design and is well proportioned, the case construction, with exposed dovetails and no dustboards, is unsophisticated. The scrolled bracket feet and the extremely elaborate raised panels of the top are outstanding features, but the dentil cornice is w eak and naive. Such discrepancies are characteristic of cabinetmaking techniques in rural areas. When the provincial tradesman endeavored to produce an elaborate or exceptional example, he often favored one or two elements, developing them extensively while cither neglecting or failing to visualize the important relationship of other elements to the overall design. As a result, the finished product lacks the subtle refinement of a sophisticated urban piece and relies on an energetic but simplistic “picking out” of several bold features. One can react to these with only a simple understanding of design, and while this desk-and-bookcase has great aspirations, it falls far short in workmanship and in an understanding of how the materials interact with each other.

Like the preceding desk-and-bookcase, this example also has through-tenoned battens on the fallboard, but here they are mitered at both ends rather than just on the top. Identical construction is also seen on the ends of small table tops made in the area.

112. Desk-and-Bookcase, southeast Virginia, circa /765. Walnut primary; yellow pine and oak secondary.

Height tid/z", width 40Vi", depth 21Va".

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (acc. no. 1910-109).

|

|

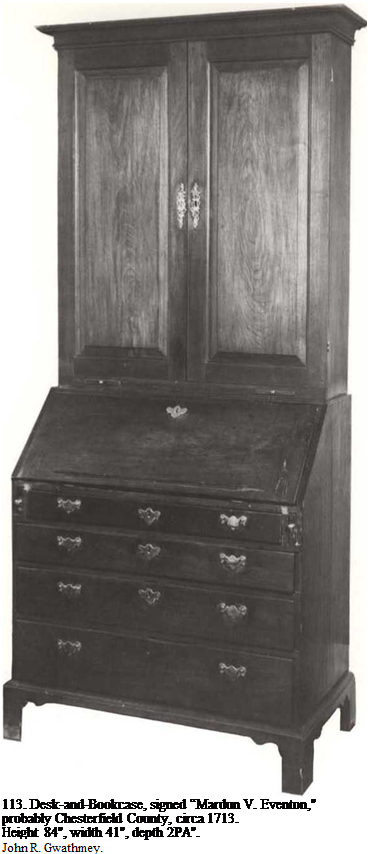

Many southeast Virginia features arc also found on a desk-and-bookcase that was probably made in Chesterfield County (fig. 113). This piece has exposed dovetails on the drawer blades, and the supports for the drawers have been nailed in since there are no dustboards. Case furniture from the region commonly has drawer supports attached like this particular example: short rosehead nails were used, each of them sunk in a V-notch formed by the removal of wood between two saw cuts.

One of the typical stylistic features of this desk is its writing interior. The outer drawers are stepped, and those that Hank the document drawers are serpentine in form. Many desk interiors produced in the Virginia Piedmont have this basic design, although here the interpretation resembles some Boston examples. The bookcase interior has been completely refitted, and while this shows considerable age, the slots for the original are clearly visible on close inspection. The bracket feet are unusually tall and arc cut from the same board as the base mold. In this respect they are typical of case pieces from the area.

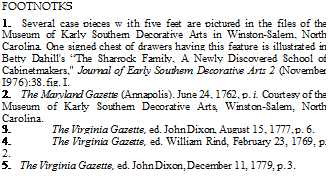

This piece bears the chalk signature “made by Mardun V. Eventon” inside the back of the desk. Eventon first advertised his cabinet business at Dumfries, in Prince William County, on June 24, 1762, w hen the Maryland Gazette carried his appeal for “Two or Three Journeymen Cabinetmakers” and “. . .two or three thousand feet of good Mahogany plank.”2 These indicate a healthy business, but his advertisements from Chesterfield fifteen years later presented quite another picture. “Wants Employment, and is now at Leisure. . .” he wrote in 1777, perhaps reflecting the economic uncertainty of the war. I lis advertisements at that point listed cabinetwork in the “Chinese” and “Gothick” taste, and ended by stating his desire to “superintend a number of hands at building.”3 It seems plausible that this desk, which descended in the Gwathmey family of nearby King William County, was made during Eventon’s Chesterfield “period.”

Mardun Eventon may not have been the only member of the Eventon family to combine the builder’s trade w ith cabinetmaking. In 1769 Maurice “Evington” of Charles City County appealed for four “regular bred” workmen, including “Two to the I louse Joiners business, one to the Cabinet, and one to the I louse, chair, and table work.”4 Little more of Maurice is known, and a decade later he offered his household furniture for sale near Four Mile Creek in I lenrico County. I lis other possessions, “sold before Mr. Freeman’s door in Richmond Town,” included a number of tools and “12 or 15 books of architecture,” including works by Swan, Pain, Langley and

|

I lalfpcnny.5 The exact relationship between Mar – dun and Maurice is unclear, but the similarity of their occupations, their geographic proximity, and their unusual surname (variously spelled “Eventon” and “Evington” in eighteenth-century documents.) point to a relatively close one.

Despite Mardun Even ton’s newspaper advertisements, which state an awareness of current fashion and architectural proportion, this desk – and-bookcasc (fig. 11 3) falls short of his claims. Even if this example w ere made at Dumfries fifteen years earlier, it would still have to be considered old – fashioned. The brasses are an early style that remained available through English catalogues and could have been ordered in provincial areas w here taste was conservative. The style of its stepped and blocked w riting interior w as popular primarily in the first third of the century, and the applied molding on the fallboard, which forms a writing or reading shelf, also comes from an early style. While it may be unfair to judge Evcnton’s work from this lone example, it appears that he was producing old – fashioned furniture of somewhat modest character. Such traits are certainly compatible with other production from this section of the state.

Despite Mardun Even ton’s newspaper advertisements, which state an awareness of current fashion and architectural proportion, this desk – and-bookcasc (fig. 11 3) falls short of his claims. Even if this example w ere made at Dumfries fifteen years earlier, it would still have to be considered old – fashioned. The brasses are an early style that remained available through English catalogues and could have been ordered in provincial areas w here taste was conservative. The style of its stepped and blocked w riting interior w as popular primarily in the first third of the century, and the applied molding on the fallboard, which forms a writing or reading shelf, also comes from an early style. While it may be unfair to judge Evcnton’s work from this lone example, it appears that he was producing old – fashioned furniture of somewhat modest character. Such traits are certainly compatible with other production from this section of the state.

The vast area of southeast Virginia could produce a volume on furniture of considerable size. The representative pieces discussed here are a small sampling, but their specific features indicate regional characteristics that typify the area and offer an interesting challenge for further study.