Selected results are reported and discussed in four separate sections of this paper, corresponding with the research issues or themes, namely aesthetic factors, cultural values and meanings, perception of personal safety and bringing up children and the perception of children’s safety.

Aesthetic factors

The postal questionnaire contained a number of questions about the visual appearance of the street where the respondents lived. Respondents were asked:

“Compared to other places you have lived, or other places you know, do you like or dislike the way your street looks?”

The respondents were asked to respond using a five point bi-polar Likert scale, with responses ranging from “Like very much” to “Dislike very much”. The data was converted to an ordinal variable with values between 1 and 5, reflecting the five categories on the Likert scale, where 5 was “like very much” and 1 was “dislike very much”. Birchwood respondents were slightly more positive about their street than their counterparts from outside: whilst 76% of Birchwood respondents said that they liked the way their street looked, or liked it very much, only 70% of the control respondents did so. However this difference was not statistically significant (Mann-Whitney Z = -0.564; NS).

The respondents were then asked whether they liked or disliked a range of specific aspects of their street including items such as “car parking”, “visual appearance of the houses” and “trees and greenery”. The data from this question was converted into a series of nominal (binary) variables, where 1 was “like” the aspect in question, and 2 was “dislike” the aspect in question, e. g. 1= like “trees and greenery” and 2= dislike “trees and greenery”. Birchwood respondents were significantly more enthusiastic about the “trees and greenery” on their street: 94% said they liked this aspect of their street compared to 85% of the control group (Chi-Square x2 = 5.895; df = 1; p = 0.015).

Somewhat surprisingly, the vegetation density of the respondents’ HCA’s had no impact on either their approval for the visual appearance of their street nor their liking for the “trees and greenery”; but there were significant trends for respondents from the higher housing density HCA’s to be more disapproving of both, though in the case of “trees and greenery” the result was only marginally significant (Table 2, Fig. 2).

|

Table 2. Effect of vegetation and housing density on respondents’ approval for the visual appearance of their street, and on their tendency to approve or disapprove of “trees and greenery”

|

These results indicate that the respondents from the higher density social housing both in and outside Birchwood were less satisfied with the way their streets looked. Did they also mean that more of these respondents disliked the “trees and greenery”? The higher level of dissatisfaction with the street found amongst these respondents is unlikely to be connected with housing density itself: there are many examples of high density housing that are highly sought after. One example is the current British fashion for so called “city living” in purpose-built high-density flats, but there are older examples such as the Barbican in the City of London. This trend is more likely to be a reflection of a lower level of satisfaction with the circumstances of daily living connected with factors such as unemployment, poverty, lower levels of educational attainment and ill health.

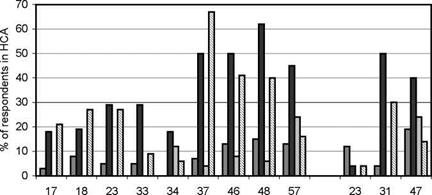

As Fig. 3 confirms respondents from the high housing density HCA’s were more likely to be unemployed, have lower levels of educational attainment, to be single parents or be over 59. Whilst these characteristics are not synonymous with deprivation, where they occur together, as in this example, it seems likely that poverty and deprivation are also present. These four factors are very similar to those used in the Index of Multiple Deprivation (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions 2000).

|

The interviews confirmed that there were differences in the perceptions of respondents from HCA’s with different housing densities; those from higher housing density HCA’s felt more dissatisfied with the way in which vegetation was being managed, and less able to take personal control of it. Housing density and housing tenure appeared to mediate respondents’ attitudes towards “trees and greenery”, through their links with choice of accommodation, size of plot, proximity of peripheral vegetation and ability to manage or control the vegetation. It should be emphasized that there was no real evidence that respondents from the high housing density HCA’s disliked “trees and greenery” per se, any more than respondents from other HCA’s. Rather, it was the proximity of the vegetation and their inability to control it that was seen as problematic. Here the comments of two respondents from high and low density housing respectively are contrasted:

Mrs. Sh: “if they kept it low enough and neat enough there’s no problem with them, and if they hadn’t planted them so close to, I mean a lot of the bushes that are round the houses are actually planted virtually against the walls, and when they’re not maintaining them properly they weigh up the walls, and it cause damp and all sorts to the houses so maybe they should have made a better plan of exactly how far they should have been planted to the house, and to brickwork and how, you know how much maintenance they were going to take in the future because when they were first put in I mean they were only little tiny things weren’t they?”

|

Control HCA’s

Housing character areas in order of increasing housing density □ Unemployed □ School to age 16 □ Single parent DOver 59 |

Fig. 3. Indicators of deprivation in housing character areas (source – postal questionnaire)

Mr. Sp: “When I had the path paved, for me the tree was just a bit too big and I was, there was some cotoneaster underneath it as well, and I wanted to make something that was a little bit less obtrusive right in the drive, I wasn’t worried about it damaging the roots ultimately affecting the house, I mean that was a reasonable distance away, I used that as an opportunity to get rid of it but I planted lower vegetation since to keep the slightly open aspect, the trees are nice on the edge if you want, we’ve got a quite small close it’s only 13 houses I don’t think it can quite cope with too many big trees.”

These issues of control and proximity highlighted the need for respondents to personalise their own living space: a need that was articulated by a number of respondents during the interviews. Many respondents from low, medium and high housing density HCA’s described how they had removed the original planting put in by the builders and contractors at the time their homes had been constructed, usually from their front gardens (Fig. 4).