In the postal questionnaire the respondents were asked whether they felt that their local area was a good place to bring up children. The data from this question was transformed into a nominal (binary) variable with values 1 and 2, where 1 signified that the respondent’s local area was a good place to bring up children and 2 signified that it was not. The respondents were then requested to give reasons for their answer to this question and these reasons were sorted into categories (e. g. “good community” and “local green spaces/green setting”).

Respondents from Birchwood were significantly more likely to feel that their local area was a good place to bring up children, compared to the control respondents (Chi-Square x2 = 6.533; df = 1; p = 0.011).

Eighty six per cent of the Birchwood respondents were positive about this issue, compared to 73% of the respondents from outside. The reasons for this positive outlook most often cited by the Birchwood respondents were reasons associated with Birchwood’s “local green spaces/green setting”.

During the interviews the value of Birchwood’s green environment for children was explored in more detail. Two main types of benefit were identified: Contact with the natural world; and the possibilities for adventurous play.

The interviews also indicated that Birchwood’s green spaces are widely used for family activities and outings.

|

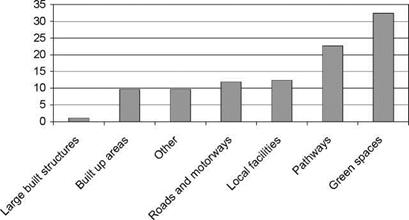

Categories of unsafe places for children Fig. 8. Respondents’ choice of unsafe places for children in the local area |

The postal questionnaire also asked the respondents to identify up to three places in the local area where they felt children would be unsafe. The respondents’ first-named places were sorted into the same categories used in relation to adults’ perception of their own safety, referred to above. “Green spaces” were most commonly identified as unsafe places for children across the whole sample (Fig. 8). It seems that there is a similar contradiction in the way that adults conceptualise their own and their children’s’ safety in “green spaces”. On the one hand many respondents believe these places make Birchwood a good place to bring up children, on the other they are also regarded as unsafe for children to be in.

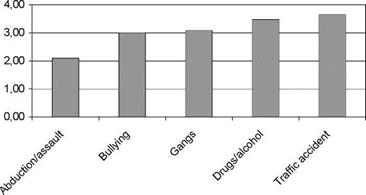

The interviews suggested that what most adults feared would happen to their children in these places was abduction or assault. In the postal questionnaire the respondents were asked to rank five potential threats in order of the magnitude of the risk they presented to children in the local area.

These threats were: “child abduction/assault”, “traffic accident”, “bullying”, “drugs/alcohol” and “involvement in gangs”. Given the finding that “green spaces” were the most commonly identified unsafe places for children and given the interview data suggesting that this was because of the risk of abduction or assault it is surprising that the greatest risk to children in the local area was actually perceived as “traffic accident” (Fig. 9), something that is clearly incompatible with “green spaces”. Perhaps this apparent contradiction has to do with the nature of the perceived risk. Although “child abduction/assault” is seen as the smallest risk, it is the most terrifying threat and the fact that “green spaces” are seen as the ideal places for this to happen invests them with a special danger.

|

Threats to children Fig. 9. Respondents’ evaluation of dangers to children in the local area |

Conclusion

What do these findings tell us about the role of naturalistic woodland in future urban landscapes? The research suggests that such woodland has the potential to be a highly valued part of the urban fabric but that the interface between people’s dwellings, the places they frequent daily and the woodland must be carefully handled. This paper suggests a conceptual approach for dealing with this interface. This approach envisages the woodland and the spaces within it as making up three different landscape zones: “the wilderness zone”, “the cultivated zone” and “the personalised zone”:

• Within “the wilderness zone” users can expect to encounter and interact closely with predominantly nature-like or even wild-looking landscapes, and conserving the integrity of these landscapes will take priority over concessions to user’s perception of their personal security.

• In “the cultivated zone” there will be clear signs of human intervention and structure including overtly “maintained” landscapes and formal or ornamental plantings, and the priority will be to maximise user’s feelings of personal safety.

• “The personalised zone” will usually consist of residents’ own homes and gardens but may also include or overlap with the street, or parts of it. In “the personalised zone” residents have control over what is planted and or how vegetation is managed.

It is not envisaged that the three zones should be discrete or separate: they can overlap or infiltrate each other. Rather, they are intended as a means of planning and designing with users’ needs in mind, and as a means of creating legible landscapes.

It should be emphasized here that this concept is somewhat oversimplified. A full account of the research findings and recommendations are outside the scope of this paper.

What the research clearly showed is that human responses to woodland are extremely diverse. To give but one example of this the research suggested that that many women do not want to enter the woodland in Birch – wood on their own confirming previous research in which gender has been found to be very significant in studies of perception of safety in urban landscapes, with women being far more fearful than men (Valentine 1989; Madge 1997; Jorgensen et al. 2002). It is therefore essential for urban landscapes containing naturalistic woodland to incorporate opportunities for individuals to choose whether to interact with the woodland. This has major implications in terms of footpath/transport networks and the strategic location of woodland in relation to places that people need to frequent to perform the activities of daily living (e. g. shops and schools).

Moreover, conventional floral displays are not the only ways of marking gateways or transitions between the so-called “wilderness” and “cultivated zones”. There are many ways in which landscape designers can express human care and intervention in the landscape and the challenge is to find innovative ways of evoking familiar responses.

References

Appleton J (1975) The Experience of Landscape. Wiley, London, UK

Bourassa S (1991) The Aesthetics of Landscape. Belhaven Press, London and New York

Burgess J (1995) Growing in confidence – understanding people’s perceptions of urban fringe woodlands. Countryside Commission, Cheltenham, UK

Burgess J, Harrison CM, Limb M (1988) People, parks and the urban green: a study of popular meanings and values for open spaces in the city. Urban Studies 25:455-473

Bussey S (1996) Public use, perceptions and preferences for urban woodlands in Redditch. Ph. D. thesis, University of Central England, Birmingham, UK

Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (2000) Indices of Deprivation. Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, London

Dowse S (1987) Landscape design guidelines for recreational woodlands in the urban fringe. Master’s dissertation, University of Manchester, UK Jorgensen A, Hitchmough J, Calvert T (2002) Woodland spaces and edges: their impact on perception of safety and preference. Landscape and Urban Planning 60(3):135-150

Kaplan R, Kaplan S (1989) The Experience of Nature. A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England Kaplan R, Kaplan S, Ryan RL (1998) With People in Mind. Island Press, Washington DC, USA

Kent M, Coker P (1992) Vegetation description and analysis – a practical approach. Belhaven Press, London, UK

Kowarik I (2005) Wild urban woodlands: Towards a conceptual framework. In: Kowarik I, Korner S (eds) Urban Wild Woodlands. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 1-32

Madge C (1997) Public parks and the geography of fear. Tijdschrift voor Econo – mische en Sociale Geografie 88(3):237-250 Manning O (1982) New Directions, 3 Designing for man and nature. Landscape Design 140:31-32

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (2003) Sustainable communities: building for the future. Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, London Orians GH, Heerwagen JH (1992) Evolved responses to landscapes. In: Barkow JH, Cosmides L, Tooby J (eds) The adapted mind – evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford University Press, New York and Oxford Rohde CLE, Kendle A. D (1994) Human well-being, natural landscapes and wildlife in urban areas. A review. English Nature, Peterborough, England Tartaglia-Kershaw M (1980) Urban woodlands: their role in daily life. Masters dissertation, Department of Landscape, Sheffield University Thompson IH (2000) Ecology, community and delight – sources of values in landscape architecture. E and F N Spon, London and New York Tregay R, Gustavsson R, (1983) Oakwood’s new landscape – designing for nature in the residential environment. Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet and Warrington and Runcorn Development Corporation. Stad och land/Rapport nr 15 Alnarp nr 15.

Valentine G (1989) The geography of women’s fear. Area 21(4):385-390 Valentine G (1997) A safe place to grow up? Parenting, perceptions of children’s safety and the rural idyll. Journal of Rural Studies 13(2):137-148