In this section, landscape changes at the inside and outside of 12 protected areas in 1988, 1996, and 2005 are presented: Chior, Bukit Kutu, Sungkai, Bukit Sungai Puteh, Endau-Kota Tinggi Barat, Endau-Kluang, Segamat, Klang Gate, Templer, Fraser’s Hill, Sungai Dusun, and Endau-Rompin Pahang wildlife reserves. Data were based on satellite image analyses using a Geographic Information System (GIS). The ‘outside’ was defined as a 5-km zone surrounding each protected area. Based on the image analysis, there are seven categories of landscape elements in the protected areas, namely, built-up area, cleared land, forest, oil palm, rubber, shrubs, and water body.

Over the three decades, forest was the primary landscape element at all protected areas (Fig. 12.4a-l). However, three patterns were observed: (1) forest declined over the years, which is very obvious in Bukit Sungai Puteh and Segamat; (2) forest fluctuated, for example, in Klang Gate and Chior; and (3) forest remained similar (e. g., Sungai Dusun and Sungkai). Between 1988 and 2005 seven of the areas had forest cover of more than 80 %: Endau-Kota Tinggi Barat, Endau-Kluang, Bukit Kutu, Fraser’s Hill, Sungkai, Sungai Dusun, and Templer. In Endau-Rompin Pahang, the proportion of forest remained above 80 % from 1988 to 1996 but became less than that in 2005. Except Sungkai and Sungai Dusun, all these areas are located in the hilly or mountainous areas of peninsular Malaysia.

Of most concern in terms of forest depletion and intensive human land use were Bukit Sungai Puteh and Segamat (Fig. 12.4a, g, respectively). In these reserves, the proportion of forest reduced tremendously and by 2005 only about 50 % remained in Segamat and 20 % in Bukit Sungai Puteh. Furthermore, both reserves are already fragmented, which could affect their effectiveness and reliability as protected areas; this is also true for Chior.

In Segamat, rubber and oil palm were the main threats to the reserve (Fig. 12.4g) whereas it was built-up areas in Bukit Sungai Puteh (Fig. 12.4a). Thus, the major human land use forming threat to wildlife protected areas depends on their location, either in remote areas or adjacent to urban regions. Elevation is also a factor that affects intrusion and the intensity of human land use. Relatively, protected areas in mountainous landscapes are less affected by human land use than those located in the lowlands (Butler et al., 2004). For example, in the three decades investigated here Bukit Kutu and Fraser’s Hill suffered less intrusion by human land use than Templer, which is located at low altitude. However, this study also suggests that low altitude does not necessarily increase human land use intensity. At those locations, the size and the management of the protected area are also important in minimizing the activity, as obviously occurred in Sungkai and Sungai Dusun, which are located in lowlands and are larger than Templer. Furthermore, these areas have staff to manage and monitor the reserves whereas Templer has none.

Connectivity to other forested areas in the surroundings is also important to minimize further intrusion of human activities into protected areas, as well as to maintain the structure and function or ecological integrity of the landscape

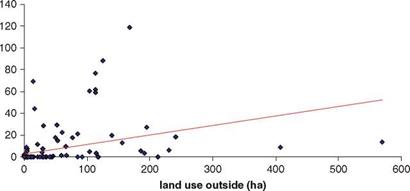

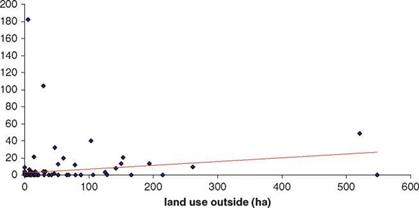

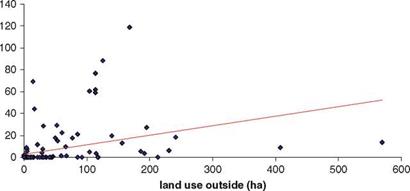

(Rizkalla and Swihart 2007). Therefore, the distribution of landscape elements at the outside of protected areas is crucial to determine the changes at the inside. Studies by Nur Hairunnisa (2011) at Krau Wildlife Reserve in 1989,1996, and 2007 revealed that the intensity of human land use at the inside was significantly correlated to that outside (Fig. 12.5a-c).

At the outside zones, Fig. 12.6a-l shows that for all areas, except Bukit Sungai Puteh and Segamat wildlife reserves, the proportion of forest was the highest during

![]()

|

|

b

Fig. 12.4 Pattern change of landscape elements of protected areas in 1988, 1996, and 2005: Bukit Sungai Puteh (a), Endau-Kota Tinggi Barat (b), Klang Gate (c), Endau-Kluang (d), Endau – Rompin Pahang (e), Fraser’s Hill (f), Segamat (g), Sungkai (h), Bukit Kutu (i), Sungai Dusun (j), Templer (k), and Chior (1). CLN cleared land, FOR forest, OIL oil palm, RUB rubber, SHR shrub, WBY water body, BLA built-up area

k

|

|

80.00

60.00

<D

03

Л

40.00

о

03

20.00

0.00

the three decades compared to other landscape elements. On one hand, this is because they are adjacent to or integral with permanent forest reserve (e. g., Sungkai, Bukit Kutu, Sungai Dusun, Templer, Endau Kota Tinggi Barat, Klang Gate, Fraser’s Hill), whereas others such as Endau-Kluang and Endau-Rompin Pahang are bordering each other as well as Endau-Rompin National Park (Johor Site). Nevertheless, there were also cases in which the proportion of forest cover gradually reduced while human land use increased. In Bukit Sungai Puteh, the surrounding area was mostly covered by built-up area and by 2005 the proportion built up was more than 50 % (Fig. 12.6a).

A similar pattern also occurred at Klang Gate, where the proportion of built-up area is likely to increase if the scenario persists. The forest cover outside Segamat

![]()

|

|

|

![]()

Wildlife Reserve was reduced and its proportion became almost the same as that for rubber and oil palm land uses (Fig. 12.6g). The largest forest patch at the outside of this reserve is part of Endau Rompin National Park. However, conditions at the outside of Chior were much better than at Segamat where the proportion of human land use was less than 30 % (Fig. 12.6l), but there is potential for this intrusion to become more severe in the near future.

|

|

a b

Landscape element Landscape element

Fig. 12.6 Pattern change of landscape elements at the outside of protected areas in 1988, 1996, and 2005: Bukit Sungai Puteh (a), Endau-Kota Tinggi Barat (b), Klang-Gate (c), Endau-Kluang (d), Endau-Rompin Pahang (e), Fraser’s Hill (f), Segamat (g), Sungkai (h), Bukit Kutu (i), Sungai Dusun (j), Templer (k), and Chior (1). CLN cleared land, FOR forest, OIL oil palm, RUB rubber, SHR shrub, WBY water body, BLA built-up area

|

|

Landscape element Landscape element