Great designers seldom make great advertising men, because they get overcome by the beauty of the picture—and forget that merchandise must be sold.1

James Randolph Adams, The International Dictionary of Thoughts, 1969

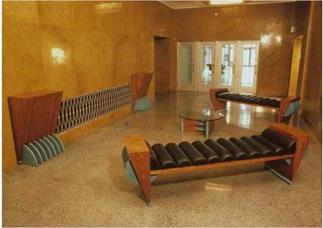

Furniture is, more often than not, a relatively expensive product to bring to market, which contributes to a limited customer pool. Further, consumers want more than comfortable and affordable furniture. Many want social status, beauty, ergonomics, structural integrity, and environmentally green design. The market is complex, driven by individual and societal needs and desires (Figure 9.1).

Furniture is, more often than not, a relatively expensive product to bring to market, which contributes to a limited customer pool. Further, consumers want more than comfortable and affordable furniture. Many want social status, beauty, ergonomics, structural integrity, and environmentally green design. The market is complex, driven by individual and societal needs and desires (Figure 9.1).

Throughout developed countries, furniture is a mature product. Most markets have been saturated in the sense that almost everyone has furniture to satisfy their basic needs. In these markets, it is the desire for new and better products that sparks demand. Furniture is conceived, fabricated, and marketed for specific niches, specific users, and specific purposes.

Marketing efforts by furniture designers and furniture companies

|

|

|

|

underscore a range of strategies due to the many different needs of consumers. Some designers and companies promote versatility of use, while others promote durability. Many promote design, which usually means well – composed, mass-produced, functional pieces. Other manufacturers promote customer satisfaction and service. Some furniture is marketed as regionally or culturally branded, such as Scandinavian design or Italian design. Some furniture is marketed as fine art, as in the case of Wendell Castle’s (Figure 9.2), George Nakashima’s, or Sam Maloof’s work. Galleries and museums collect selected pieces because of their craft, social meaning, cultural significance, or innovation in terms of material use or fabrication processes (Figure 9.3). A small amount of furniture is acquired by galleries and museums and sold through auction and estate sales to collectors. Many office furnishings are branded as ergonomic products (Figure 9.4), including the Aeron, Leap, and Freedom chairs. Uniqueness is a desirable quality for some such as HaG’s Capisco chair (1984), while others prefer the value of regularity or timeless classicism as in Cassina’s Cab chair (1977).

underscore a range of strategies due to the many different needs of consumers. Some designers and companies promote versatility of use, while others promote durability. Many promote design, which usually means well – composed, mass-produced, functional pieces. Other manufacturers promote customer satisfaction and service. Some furniture is marketed as regionally or culturally branded, such as Scandinavian design or Italian design. Some furniture is marketed as fine art, as in the case of Wendell Castle’s (Figure 9.2), George Nakashima’s, or Sam Maloof’s work. Galleries and museums collect selected pieces because of their craft, social meaning, cultural significance, or innovation in terms of material use or fabrication processes (Figure 9.3). A small amount of furniture is acquired by galleries and museums and sold through auction and estate sales to collectors. Many office furnishings are branded as ergonomic products (Figure 9.4), including the Aeron, Leap, and Freedom chairs. Uniqueness is a desirable quality for some such as HaG’s Capisco chair (1984), while others prefer the value of regularity or timeless classicism as in Cassina’s Cab chair (1977).

One priority that drives the vast majority of new works is the desire to make a similar product for less cost. This often results in reducing the quality of furniture’s unseen aspects, relocating production to regions of the world where labor is less expensive, or increasing the technological efficiencies involved in the production of furniture.

Although it is correct to assume that designers and furniture companies respond to market demand, it is also correct to infer that they create market demand. Revolutionary designs take the market by surprise. Few people felt the need for inflated therapy or gym balls, beanbag chairs, or tubular metal chairs when these products first became available.

In some cases, designers anticipate a potential market and, by providing a solution, fill an emerging demand. The bentwood (ready-to-assemble) beech chairs of GebrQder Thonet point to a match between these lightweight, inexpensive chairs and the restaurants, cafes,

and residential spaces that emerged throughout Europe during the mid-nineteenth century. The inspiration behind these chairs arose from an infusion of design, technology, cultural reflection, and sensitivity rooted in the idea of zeitgeist (the spirit of the times). The beech bentwood chairs produced in the late 1800s inspired generations of modern designers and contemporary fabrication companies (Figure 9.5).

Staff designers are full-time company employees who design and develop products in collaborative working environments for carefully researched markets. Some furniture companies, such as Steelcase and Luxo Italiano, employ staff designers. They pursue specialized market niches by identifying their customer base and determine how best to reach it. Other furniture companies, such as Alias,

Staff designers are full-time company employees who design and develop products in collaborative working environments for carefully researched markets. Some furniture companies, such as Steelcase and Luxo Italiano, employ staff designers. They pursue specialized market niches by identifying their customer base and determine how best to reach it. Other furniture companies, such as Alias,

Cassina, Herman Miller, Knoll, and B & B Italia, seek outside designers under contract and consulting arrangements. In some cases, designers must work only for the specific company, but in most cases, designers are free to consult with as many companies as they choose to be affiliated with. Philippe Stark is an international design consultant who works with several prominent companies, such as Alessi and Kartell (Figure 9.6).

Furniture designers are the principal talent behind the furniture design industry. At the end of the day, relatively few furniture designers make a living solely on the income produced by royalties from designing furniture.

Designers rely on opportunities extended by clients, building and interior commissions, industry, companies, galleries, museums, writers, and other marketing, branding, or promotional venues. Designers also work as entrepreneurs forming business relationships with furniture or production companies, actively seeking innovative products and venues to bring new ideas to industry and forming potential business partnerships.

Other opportunities require a more diverse approach to the career. As an architect or interior designer, one can concentrate on the custom design of specific or limited – production furniture pieces that result from new construction, renovation, and interior design commissions.

At the end of the day, those who design furniture work hard to forge their opportunities and, in doing so, often develop a professional niche within their career. Some professional niches are singular, career-long investments focused on specific activities—such as the work of George Nakashima and Sam Maloof—while others

weave in and out of several disciplines as a means of generating an evolving career with periodic concentration on furniture design, such as the careers of Zaha Hadid and Karim Rashid. One rarely chooses the career path, but paths develop and emerge as a natural course of professional activity, be it the path of the artist, the industrial designer, the architect, the interior designer, the entrepreneur, the collaborator, the fabricator, the engineer, the social activist, the teacher, or the one in charge of marketing, branding, selling, or writing about furniture design.

weave in and out of several disciplines as a means of generating an evolving career with periodic concentration on furniture design, such as the careers of Zaha Hadid and Karim Rashid. One rarely chooses the career path, but paths develop and emerge as a natural course of professional activity, be it the path of the artist, the industrial designer, the architect, the interior designer, the entrepreneur, the collaborator, the fabricator, the engineer, the social activist, the teacher, or the one in charge of marketing, branding, selling, or writing about furniture design.

To achieve success within the discipline, one often must wear several disciplinary hats—that is, the artist can be the fabricator and sometimes the curator. The industrial designer may consult broadly within the industry and work full-time with a particular company. Mario Bellini and Ettore Sottsass were successful in doing so by working for Olivetti and other companies throughout their early career. An educator might teach and write about furniture, and practice on the side. The architect and interior designer may have opportunities to design custom pieces of furniture through their professional practice in designing buildings and working on interior renovations. The engineer can influence and resolve design matters from schematic design through production and either work as a consultant to many offices or remain employed within a single company.

Through the various processes and opportunities of contemporary practice, designers collaborate with fabricators, artists with industrial entrepreneurs, engineers with project managers, and architects with clients, all contributing to the resolution of products and their improved use, dissemination, and acceptance by society. Success, in turn, gives voice to the industry, which promotes design awareness and cultural affinity for furniture design.