united States

The plantation owners in the new American colonies turned to England for furnishings, but the vast majority of colonists were ordinary people from a variety of different cultures, who depended on what they could bring with them on their voyage or had to build their furniture from local woods. For these people, furniture was fabricated using primitive and regional woodworking technology.

The table became an important furnishing in the colonial home during the midseventeenth century. It created a centered spatial zone in the home that was useful for work, social gatherings, tea, and shared conversations throughout the day. The American gateleg table was used as an oval table in the center of the room and as a drop-leaf table placed against a wall (Figure 10.36).

Among the few personal possessions that traveled with families, chests were the primary furnishings brought from Europe. After a newly arrived family settled into a home, local lumber was used to craft additional furnishings. Wood turners could work with green (unseasoned) wood such as white oak, ash, and red oak. In 1642, records from a joiner named Edward Johnson noted that towns were fast turning into urban communities.7 The growing urban populations began to divide societies into trades and services.

William and Mary furniture (1689-1702) was named after Queen Mary, sister of King James II, and her Dutch husband, William of Orange. With their ascendancy to the English

|

|

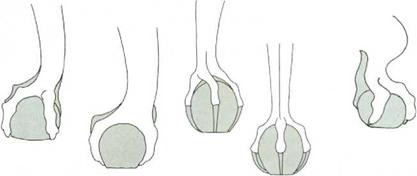

Figure 10.38 American Chippendale—ball-and-claw variations from left to right: Philadelphia foot with prominent knuckles; squared-off New York foot; Newport foot with undercut talons; Newport foot, front view; Boston foot with rear-curving talon. Photography by Jim Postell, 2006. |

throne, several Dutch craftsmen emerged, whose collective work was influenced by Flemish design. The furniture under their reign was lighter and improved due to the strength of the wood used and the tools and methods employed in fabrication. What we now call highboy (Figure 10.37) and lowboy were characteristic of William and Mary styling and were central furniture pieces in the homes of the affluent.

throne, several Dutch craftsmen emerged, whose collective work was influenced by Flemish design. The furniture under their reign was lighter and improved due to the strength of the wood used and the tools and methods employed in fabrication. What we now call highboy (Figure 10.37) and lowboy were characteristic of William and Mary styling and were central furniture pieces in the homes of the affluent.

Queen Anne (1702-1714) and the Age of Regionalism followed the reign of William and Mary. Although Queen Anne ruled England for only 12 years, this stylistic period lasted for nearly 40 years. In this era, the cabriole leg, the distinctive splat back, and the use of upholstery that emerged in the seventeenth century were renowned characteristics of the famous Queen Anne padfoot and ball-and-claw-foot chairs (Figure 10.38). Significant is the fact that these chairs were fabricated by individual components and made to order. This generated great variety in both design and production. Major urban centers throughout

colonial settlements began to take on an ethnic or culturally unique characteristic of place enhanced by locally available material and local skill in furniture making. As a result, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia developed as distinct design centers reflecting popular local tastes. By the time of the Revolutionary War in 1776, 150 cabinetmakers were listed as working in Boston.

Newport, Rhode Island, was home to the Quaker family of cabinetmakers Goddard and Townsend. They were known for block front and shell carved dressing tables and secretary bookcases. Their furniture pieces were fabricated from Honduran mahogany and were typically carved rather than inlaid. For over 30 years, Newport was a furniture-producing center where beautiful mahogany pieces for Newport’s mercantile elite were fabricated.

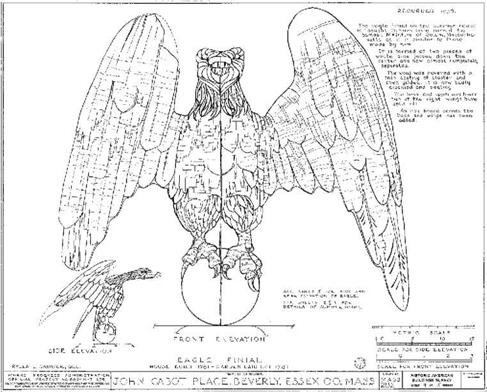

The official treaty signed between the French, the British, and the American colonists on September 3, 1782, ended the struggle for independence and marked the return to peace and a fresh beginning for those living in the new United States. With a new sense of liberty, the Federal style (1780-1830) emerged, reflecting the aspirations of the republic. It was a classical style inspired by a renewed spirit of nationalism in conjunction with an interest in architecture and metaphor. The eagle, an ancient Roman Republican symbol, was adopted as an American symbol shortly after 1776. The American eagle served as an emblematic element in wood veneer and carved pieces found in buildings, in interiors, and on furniture (Figure 10.39). In addition, brass handles, knobs, and escutcheons were added for decoration. Cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe (1768-1854) and carver Samuel Mclntire (1757-1811) were craftsmen who produced beautiful Federal-style work during this period.

|

Figure 10.39 Eagle finial designed for John Cabot Place, Essex Co., Massachusetts. Library of Congress 00004a. Courtesy of Corky Binggeli, Interior Design: A Survey (John Wiley & Sons, 2007). |