The Persians have from time immemorial been an artistic people, and their style of Art throughout successive conquests and generations has varied but little.

Major-General Murdoch Smith, R. E., the present Director of the branch of the South Kensington Museum in Edinburgh, who resided for some years in Persia, and had the assistance when there of M. Richard (a well-known French antiquarian), made a collection of objets d’art some years ago for the Science and Art Department, which is now in the Kensington Museum, but it contains comparatively little that can be actually termed furniture; and it is extremely difficult to meet with important specimens of ornamental wordwork of native workmanship. Those in the Museum, and in other collections, are generally small

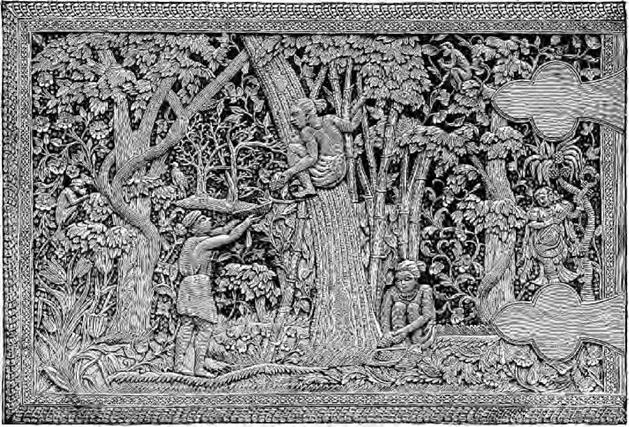

ornamental articles. The chief reason of this is, doubtless, that little timber is to be found in Persia, except in the Caspian provinces, where, as Mr. Benjamin has told us in "Persia and the Persians," wood is abundant; and the Persian architect, taking advantage of his opportunity, has designed his houses with wooden piazzas—not found elsewhere—and with "beams, lintels, and eaves quaintly, sometimes elegantly, carved, and tinted with brilliant hues." Another feature of the decorative woodwork in this part of Persia is that produced by the large latticed windows, which are well adapted to the climate.

|

|

|

|

In the manufacture of textile fabrics—notably, their famous carpets of Yezd and Ispahan, and their embroidered cloths in hammered and engraved metal work, and formerly in beautiful pottery and porcelain—they have excelled: and examples will be found in the South Kensington Museum. It is difficult to find a representative specimen of Persian furniture except a box or a stool; and the illustration of a brass incense burner is, therefore, given to mark the method of design, which was adopted in a modified form by the Persians from their Arab conquerors.

|

|

This method of design has one or two special characteristics which are worth noticing. One of these was the teaching of Mahomet forbidding animal representation in design—a rule which in later work has been relaxed; another was the introduction of mathematics into Persia by the Saracens, which led to the adoption of geometrical patterns in design; and a third, the development of "Caligraphy" into a fine art, which has resulted in the introduction of a text, or motto, into so many of the Persian designs of decorative work. The combination of these three characteristics have given us the "Arabesque" form of ornament, which, in artistic nomenclature, occurs so frequently.

The general method of decorating woodwork is similar to that of India, and consists in either inlaying brown wood (generally teak) with ivory or pearl in geometrical patterns, or in covering the wooden box, or manuscript case, with a coating of lacquer, somewhat similar to the Chinese or Japanese preparations. On this groundwork some good miniature painting was executed, the colours being, as a rule, red, green, and gold, with black lines to give force to the design.

The author of "Persia and the Persians," already quoted, had, during his residence in the country, as American Minister, great opportunities of observation, and in his chapter entitled "A Glance at the Arts of Persia," has said a good deal of this mosaic work. Referring to the scarcity of wood in Persia, he says: "For the above reason one is astonished at the marvellous ingenuity, skill, and taste developed by the art of inlaid work, or Mosaic in wood. It would be impossible to exceed the results achieved by the Persian artizans, especially those of Shiraz, in this

wonderful and difficult art…. Chairs, tables, sofas, boxes, violins, guitars, canes,

picture frames, almost every conceivable object, in fact, which is made of wood, may be found overlaid with an exquisite casing of inlaid work, so minute sometimes that thirty-live or forty pieces may be counted in the space of a square eighth of an inch. I have counted four hundred and twenty-eight distinct pieces on a square inch of a violin, which is completely covered by this exquisite detail of geometric designs, in Mosaic."

Mr. Benjamin—who, it will be noticed, is somewhat too enthusiastic over this kind of mechanical decoration—also observes that, while the details will stand the test of a magnifying glass, there is a general breadth in the design which renders it harmonious and pleasing if looked at from a distance.

In the South Kensington Museum there are several specimens of Persian lacquer work, which have very much the appearance of papier mache articles that used to be so common in England some forty years ago, save that the decoration is, of course, of Eastern character.

Of seventeenth century work, there is also a fine coffer, richly inlaid with ivory, of the best description of Persian design and workmanship of this period, which was about the zenith of Persian Art during the reign of Shah Abbas. The numerous small articles of what is termed Persian marqueterie, are inlaid with tin wire and stained ivory, on a ground of cedar wood, very similar to the same kind of ornamental work already described in the Indian section of this chapter. These were purchased at the Paris Exhibition in 1867.

Persian Art of the present day may be said to be in a state of transition, owing to the introduction and assimilation of European ideas.