Angela Paxton

INTRODUCTION

Consumers in rich industrialised countries are accustomed to being able to choose from the global breadbasket whenever they go to the local supermarket. A UK shopper can buy grapes from Chile, green beans from Kenya and bottled water from Canada. However these food choices do not come cheaply: there is a whole range of environmental, social and economic costs which result from the increasing long distance trade in foods.

The distance food travels, as well as being environmentally damaging directly through transport emissions, adversely affects the way food is grown and treated on its journey along the various links in the food chain. There are also impacts for food producers, particularly small farmers and growers trying to compete in a global marketplace, and for consumers, who are eating more long distance, treated food and products rather than fresher, local foods.

The separation of consumption from production results in the psychological distancing of food producers from consumers, with shoppers having little idea about the many implications of their food buying habits. This consumer ignorance allows yet more abuses of the environment, people and animals, which might not be tolerated if they were happening closer to home.

This chapter will highlight the impacts of our transport-dependent food system, look at the forces behind the food miles and explore what can be done to reduce and alleviate the impacts of long distance food distribution.

THE FOOD MILES FOOD CHAIN Agriculture

Long distance trade in foods leads to specialisation in farming and the use of local resources for export to other regions or countries rather than for local consumption. Thus crops will be grown over large areas in industrialised conditions to achieve economies of scale and cut costs in order to compete with growers elsewhere. Producers will concentrate on growing a small number of crops, using varieties specified by food manufacturers or retailers for particular qualities, such as their ability to withstand long periods in transit and storage, or their suitability for processing. Crops grown in monocultures are easy prey to pests and diseases, which quickly become resistant to agro-chemicals, and farmers find themselves on a ‘chemical treadmill’, having to apply increasing amounts of pesticides and herbicides.

Transport

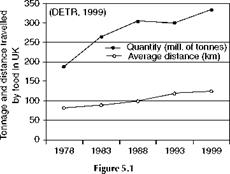

Essentially, food miles can take two forms: transport within a country as a result of the centralised distribution systems of large retailers and food manufacturers, and transport between countries as nations import and export fresh and processed food products. Within the UK, food, drink and tobacco were responsible for a third of the growth in road freight between 1978 and 1993. Meanwhile the transport of food and drink products around the UK increased by 50 per cent in the past 15 years, while the amount of food being transported increased by only 16 per cent, see Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Comparison of the average distance and total quantity of food transported in the UK between 1978 and 1999.

|

|

Internationally too, food transport is on the increase. UK farmers rely on exports while British consumers buy increasing amounts of imported food. The UK trade gap in food and drink increased from £3.5 billion in 1980 to £8.3 billion in 1999. The UK now imports a variety of foods, such as apples, carrots and onions that can be grown here, even when they are in season. Countries often import and export substantial quantities of the same food products: in 1997 the UK imported 126 million litres of milk and exported 270 million litres, see Figure 5.2.