|

|

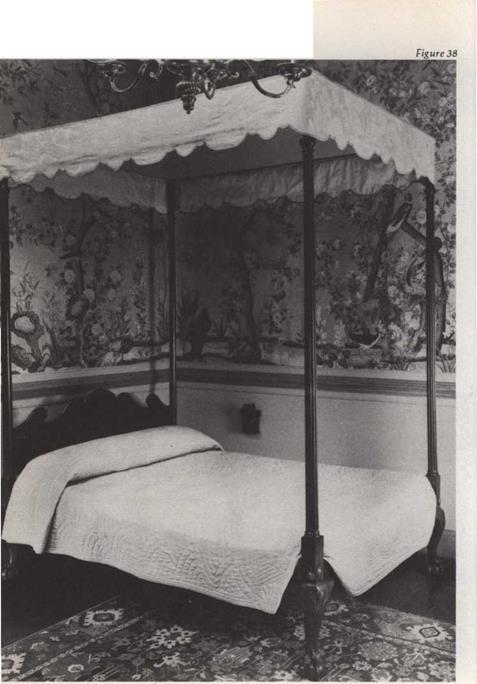

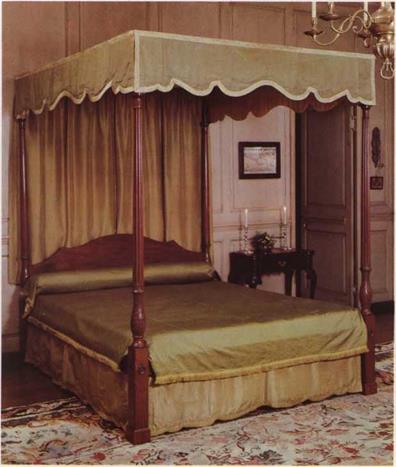

Figure 38. Bed. The only stylish feature of this high-post bedstead is fluted decoration on the footposts. Though Philadelphians were generally more style conscious than New Yorkers, there was a market for Queen Anne forms and decoration in Philadelphia throughout the Chippendale period.

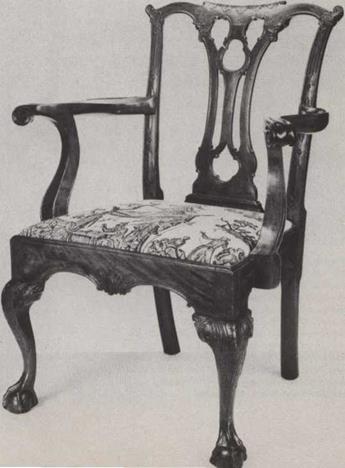

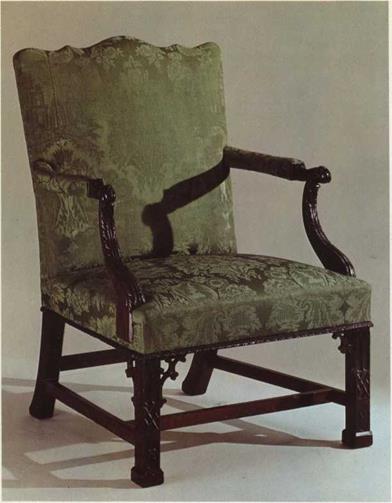

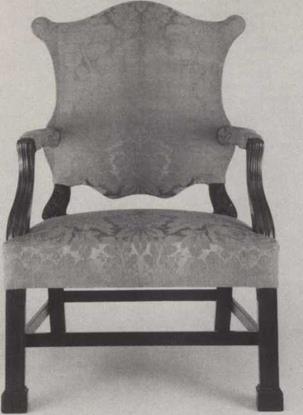

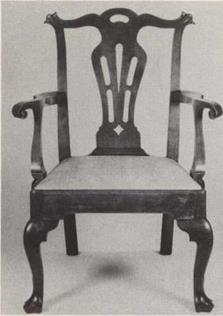

Poplar was the common wood for bedsteads. In 1777, George Haughton, a Philadelphia upholsterer, advertised for sale "poplar scantling fit for bedsteads.",г Fig. 38: mahogany; 1755-70; H 96V (245.6 cm), L 79V (202.6 cm); acc. no. G57.29. Figure 39. Armchair. Plate XIII (1754 ed.) and Plate X(1762 ed.) of the Director provided the design for this fashionable armchair. Related Philadelphia chairs bear the label of fames Gillingham (1736-81), but a number of cabinetmakers could have copied the pattern. Rounded or chamfered-edge stump rear legs, pronounced ears terminating the crest rail, S- or reverse-curved armrests ending in scrolled volutes (knuckles), and side rails of the seat tenoned through a mortise in the rear legs (Fig. 51b) are all features of Philadelphia chairs in this period. Fig. 39: mahogany, tulip; 1760-75; H 38 V (97.1 cm) acc. no. G57.666.

Figure 39

|

|

|

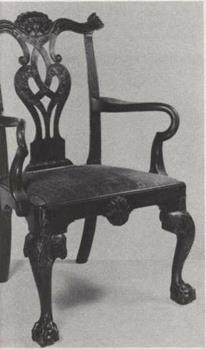

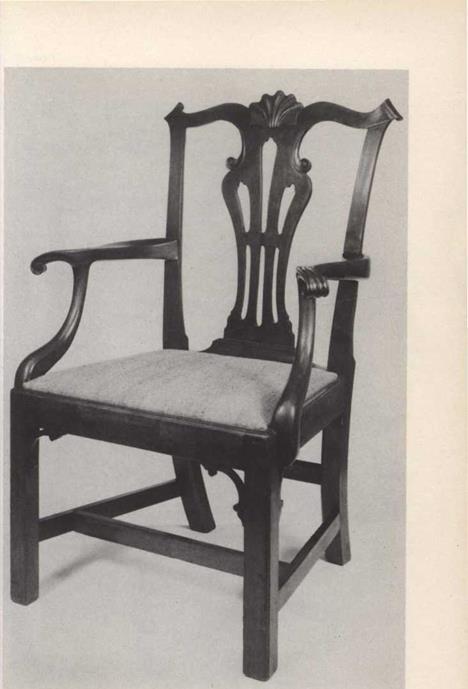

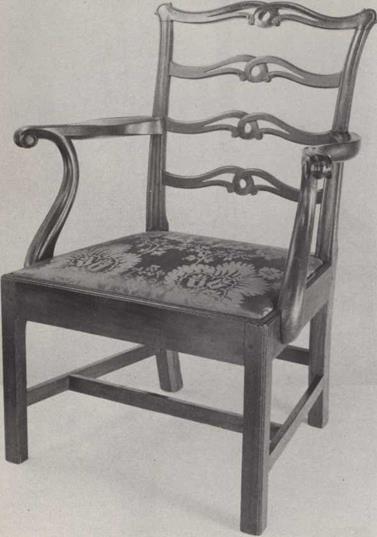

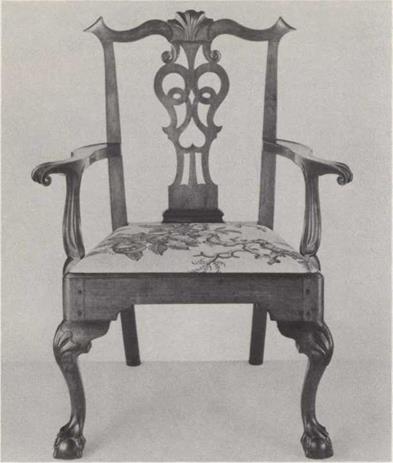

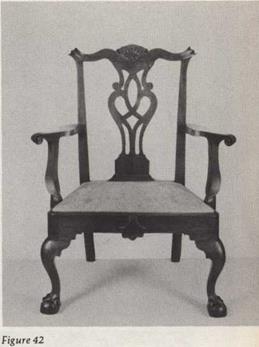

Figures 40, 41, and 42. Armchairs. Walnut, a popular cabinet wood of the Queen Anne period, remained in favor in Philadelphia throughout the Chippendale period (Figs. 40,42). During the English occupation of Philadelphia (1777-78), a storekeeper, William Rush, found that 30 pieces of walnut furniture had been moved into his house by the enemy, including a walnut armchair with blue damask bottom.13 The splat of Figure 40 also occurs on New York and New England chairs, but the stump rear legs, pronounced ears, high-relief carving, reverse S-curve armrests, and shaped

arm supports are all hallmarks of Philadelphia furniture shared by these chairs. Carved rococo shells adorn the center of the cresting rails of Figures 41 and 42. The former, a fashionable mahogany armchair, has looped arms, a Queen A nne-style feature of English origin rarely used by American cabinetmakers.

It is part of a set of chairs (Fig.

It is part of a set of chairs (Fig.

65) that were in the Philadelphia residence of George Washington during his presidency.14 Fig. 40: walnut, arborvitae; 1760-70; H 41 (105.4

cm); acc. no. G60.1074. Fig. 41: mahogany, white pine; 1760-85; H 424»" (107.3 cm); acc. no. G58.2256.

Fig. 42: walnut; 1760-70; H 40" (101.6 cm); acc. no. G57.531.

|

Figure 41

|

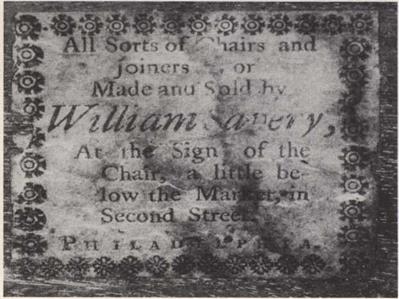

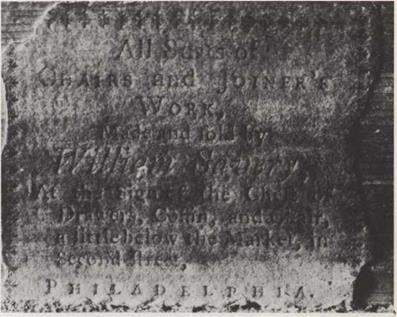

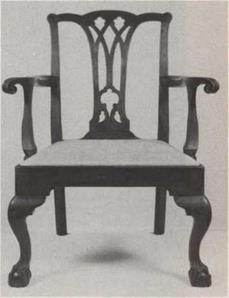

Figures 43 and 44. Armchairs. It is futile to assign a rural or urban origin to furniture solely on the basis of aesthetic criteria.15 These armchairs, made by William Savery (1721-88), area case in point. At least one author believes that trifid feet (Fig. 43) were customary on Philadelphia plain chairs throughout the Chippendale period.16 With the exception of their pierced splats; large, cabochonlike, shaped ears on one (Fig. 43); and beading to outline crest rails, stiles, and armrests these chairs are quite plain. Ironically, because the first example of labeled Philadelphia furniture to be published bore Savery’s name, indiscriminate attributions to much

Figures 43 and 44. Armchairs. It is futile to assign a rural or urban origin to furniture solely on the basis of aesthetic criteria.15 These armchairs, made by William Savery (1721-88), area case in point. At least one author believes that trifid feet (Fig. 43) were customary on Philadelphia plain chairs throughout the Chippendale period.16 With the exception of their pierced splats; large, cabochonlike, shaped ears on one (Fig. 43); and beading to outline crest rails, stiles, and armrests these chairs are quite plain. Ironically, because the first example of labeled Philadelphia furniture to be published bore Savery’s name, indiscriminate attributions to much

![]()

elaborate Philadelphia furniture were made.

elaborate Philadelphia furniture were made.

For more than 40 years, however, he

prospered by constructing simple, well-made

furniture (see Fig. 77). Savery made

all sorts of chairs and joiner’s work in

his shop, “a little below the Market" in

Second Street. Earlier, the "Sign of

the Chair" hung over its entrance, but

later, that sign was changed to

include a "Chest of Drawers, Coffin,

and Chair." Fig. 43: walnut, yellow

pine: 1755-65; H 40" (101.6 cm);

асе. no. C58.2680. Fig. 44:

mahogany, white cedar, yellow pine,

tulip; 1765-80; H 37V (95.8 cm);

асе. no. C60.149.

|

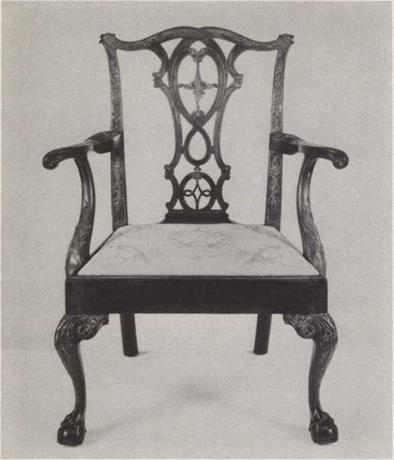

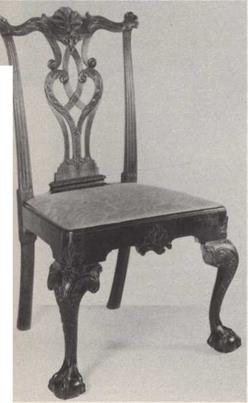

Figure 45. Armchair. The design of this chair, inspired by Plate XVI of Chippendale’s Director (1762 ed.), must have been popular. The chair matches a set of side chairs once owned by John Dickinson, now at Stenton, and is similar to an armchair made for Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress, as well as a set of side chairs at Winterthur (Fig. 68).17 The best cabinetmakers and carvers in Philadelphia understood that the glory of Chippendale style was ornament. But they also understood the effects of contrast achieved if some surfaces were left plain. This chair’s splat was made to appear as an interlaced ribbon. Floral, husk, and leaf carving in high relief decorates its crest rail, stiles, armrests, arm supports, front legs, and knee brackets. Fig. 45: mahogany, white cedar, yellow pine, tulip; 1765-80; H 38%" (98.4 cm); no. ХІІП in a set; acc. no. C61.116. |

Plate V. Bed. Late in the Chippendale period, reeded posts began replacing "fluted pillars" on bedsteads made in Philadelphia and elsewhere.

In Philadelphia, bedsteads were sold in combinations ranging in price from a poplar low-post bedstead at 18 shillings to a fluted-and-carved mahogany one at 10 pounds. Adding the cost of European silk taffeta hangings to an all-mahogany caroed-and-reeded bedstead (as in the rare bed illustrated) meant a significant expense. PI. V: mahogany; 1780-90; H 95’k" (241.6 cm), L 90% " (230 cm); acc. no.

C55.787.

Plate V

|

|

|

|

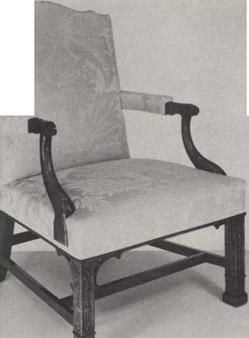

Plate VI. Armchair. This armchair is related to another that was presumably made for Governor John Penn (Fig. 48), and the fret carving on its legs also appears on the Marlborough legs of a sofa made by Thomas Affleck (w. 1763-95) for the governor. Here, the rococo leaf-carved knuckles of its armrests, pierced C-scroll leg brackets, and blind frets carved in Gothic and Chinese designs help create a sophisticated chair. European green silk damask (ca. 1725) covers this example. PI. VI: mahogany, white oak; ca.

1770; H 40" (101.6 cm); acc. no. G56.30.1.

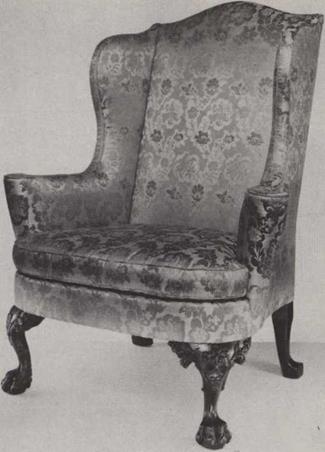

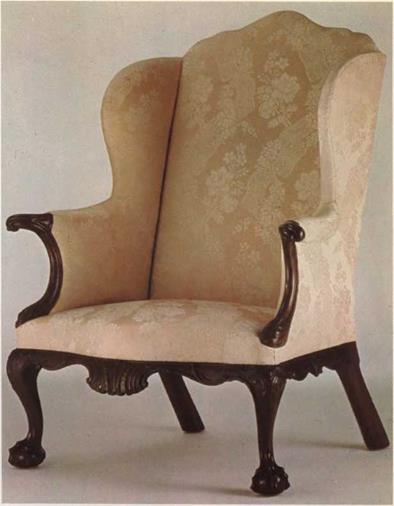

Plate VII. Easy Chair. Philadelphia easy chairs are usually upholstered over the seat rails (PI. VIII). Occasionally, chairmaker, carver, and upholsterer combined to produce the exceptional type shown here (cf. PI. IX). Its mahogany seat rails and arm supports were left partially uncovered to receive leaf, scroll, and pendant carving; armrest terminals twist outward to provide the unbalanced look of high-style Chippendale-period design. Its upholstery is peach and white French silk (ca. 1725). PI. VII: mahogany, yellow pine, white oak; 1760-75; H 45" (114.3 cm); асе. no. C57.665.

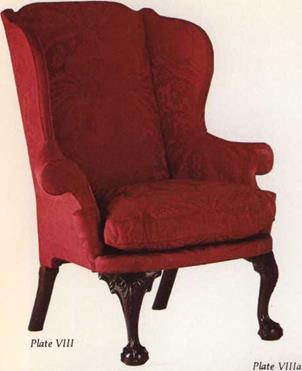

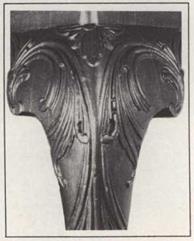

Plate VIII. Easy Chair. Horizontal rolled armrests, vertical rolled arm supports—the two forming a C-scroll —upholstered seat rail, and stump rear legs are usual features of Philadelphia easy chairs. Cyma-curved wings return sharply into the armrests in a curvilinear design retained from the Queen Anne style. Carved leaves radiate from a C-scrolled halfcartouche on its knees (PI. Villa). Elegant simplicity, a hallmark of fine Philadelphia craftsmanship, is everywhere apparent. The upholstery is Italian red silk damask (1740-60).

Easy chairs, frequently used in bed chambers in the 18th century, are now usually placed in living rooms. PI.

VIII: mahogany, yellow pine; 1760-75; H 46Vs" (117.1 cm); acc. no.

G59.1202.

G59.1202.

|

|

|

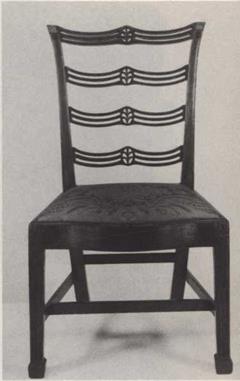

|

Figures 46 and 47. Armchairs. The splat and crest rail of Figure 46 (page 57) is related to other Philadelphia armchairs (Fig. 40). In 1789, Daniel Trotter (w. 1761-80) billed Stephen Girard for a set of six chairs of the type illustrated in Figure 47.

The shape of its pierced slats, or splats, has given rise to the term pretzel back for this type of chair. Introduced late in the Chippendale period, it may have been first described in a 1772 Charleston, S. C., advertisement for "carved chairs of the newest fashion, splat Backs, with hollow slats and commode fronts, of the same Pattern as those imported by Peter Manigault, Esq."ls Fig. 46: mahogany; 1760-75; H 394s" (101.3 cm); no. Ill in a set, one of a pair; acc. no. G57.105.1. Fig. 47: mahogany, arbor- vitae; 1775-90; H 38’U" (97.1 cm); no. linaset; acc. no. G59.1486.

Figure 48. Armchair. Chippendale called armchairs of this type "French chairs with Elbows." This one is said to be part of a set made by Thomas Affleck (w. 1763-95) for Governor John Penn that was bought by Philadelphians at the sale of Penn’s furnishings in 1788.19 Similar upholstered armchairs (Pi. VI) are attributed to Affleck. The bead-and-pellet carved molding, an improvement over the design illustrated by Chippendale; relief – carved bellflower and husk in the inset panels of the Marlborough legs; C-scroll brackets; and carved armrest terminals would have cost extra to an initial purchaser. Fig. 48: mahogany; 1760-70; H 42Vs" (107.3 cm); acc. no.

Figure 48. Armchair. Chippendale called armchairs of this type "French chairs with Elbows." This one is said to be part of a set made by Thomas Affleck (w. 1763-95) for Governor John Penn that was bought by Philadelphians at the sale of Penn’s furnishings in 1788.19 Similar upholstered armchairs (Pi. VI) are attributed to Affleck. The bead-and-pellet carved molding, an improvement over the design illustrated by Chippendale; relief – carved bellflower and husk in the inset panels of the Marlborough legs; C-scroll brackets; and carved armrest terminals would have cost extra to an initial purchaser. Fig. 48: mahogany; 1760-70; H 42Vs" (107.3 cm); acc. no.

G57.668.

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

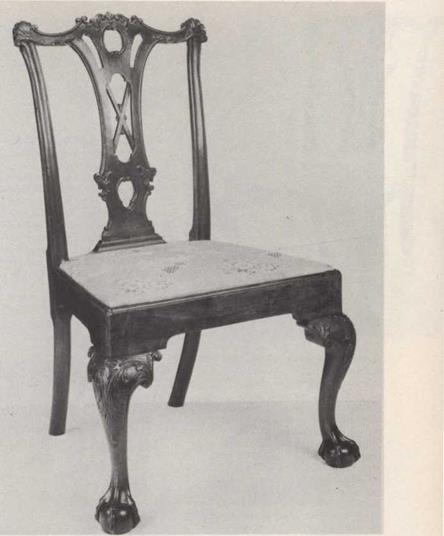

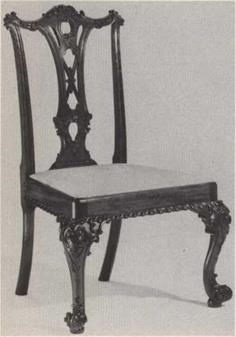

Figure 51. Side Chair. Perhaps because this chair was copied from Plate XII (1754 ed.) or Plate ХІПІ (1762 ed.) of the Director, the scroll foot preferred by Chippendale was used. Every detail of the splat and crest rail (Fig. 51a), including carving in very high relief, is employed here. The effect of ornamentation on the front legs and feet is that of architectural carving or wood sculpture. Typically, the side rails of this chair are tenoned through mortises in the rear stump legs (Fig. 51b). Carved gadrooning, used sparingly in Philadelphia, does occur on other chairs and tables (Figs. 53, 64, 96-97, 99-100, 105). Fig. 51: mahogany, white cedar; 1760-80; H 39% " (100.9 cm); no III in a set, one of a pair; асе. no. C60.1062.1.

|

Figure 51b

|

|

Figure 52. Side Chair. Perusal of a variety of Philadelphia side chairs shows that shaping the lower edges of seat rails relieved the visual problem posed by wide, straight, undecorated rails. The fact that side chairs were usually made in sets is illustrated by the advertisement of George Haughton, a Philadelphia upholsterer, for the sale of "several half dozens of good mahogany chairs."21 Fig. 52: mahogany; 1760-80; H 40’U“ (102.2 cm); no. VIII in a set, one of three; acc. no. G60.1067.1. |

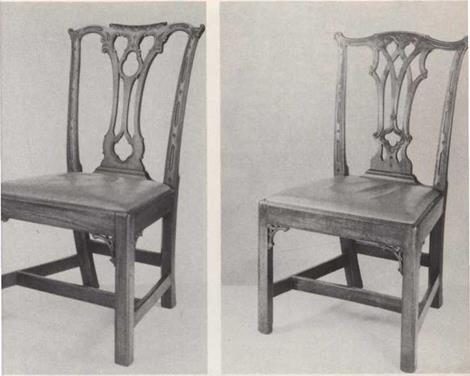

sides of the quatrefoil; provide claw-and-ball feet and Figure 54 emerges. A side chair in the Garvan Collection, Yale University, is identical to Figure 55 and bears the label of Benjamin Randolph (1737/38-39). Differences in carving technique and construction indicate, however, that Figures 53-55 were not made in the same shop. Fig. 53: mahogany, arborvitae; 1765-80; H 38" (96.5 cm); one of four; acc. no. G60.1066.2. Fig. 54: mahogany; 1760-80; H 38’M" (96.8 cm); no. VII ‘ in a set, one of four; acc. no.

G59.3391. Fig. 55: mahogany, white cedar, white oak; 1760-70; H 37" (94 cm); no. Ill in a set; acc. no.

G59.3391. Fig. 55: mahogany, white cedar, white oak; 1760-70; H 37" (94 cm); no. Ill in a set; acc. no.

G61.1200.1.

![]()

Figures 53, 54, and 55. Side Chairs. Gothic arch and quatrefoil pierced splats were a popular Philadelphia design. The variety possible by playing with a single theme is well illustrated by these chairs. Eliminate carving, pierce the crest rail, use plain Marlborough legs and presto, Figure 55. Substitute hairy-paw feet for the usual claw-and-ball; add carved gadrooning to the front seat rail and to the upper edge of the shoe; partially upholster the seat rail and finish it with brass nails as advocated by Chippendale and Figure 53 is the result. Use C-scrolls and a carved leaf centered on the front seat rail; pierce the splat below and to the

Figures 53, 54, and 55. Side Chairs. Gothic arch and quatrefoil pierced splats were a popular Philadelphia design. The variety possible by playing with a single theme is well illustrated by these chairs. Eliminate carving, pierce the crest rail, use plain Marlborough legs and presto, Figure 55. Substitute hairy-paw feet for the usual claw-and-ball; add carved gadrooning to the front seat rail and to the upper edge of the shoe; partially upholster the seat rail and finish it with brass nails as advocated by Chippendale and Figure 53 is the result. Use C-scrolls and a carved leaf centered on the front seat rail; pierce the splat below and to the

|

|

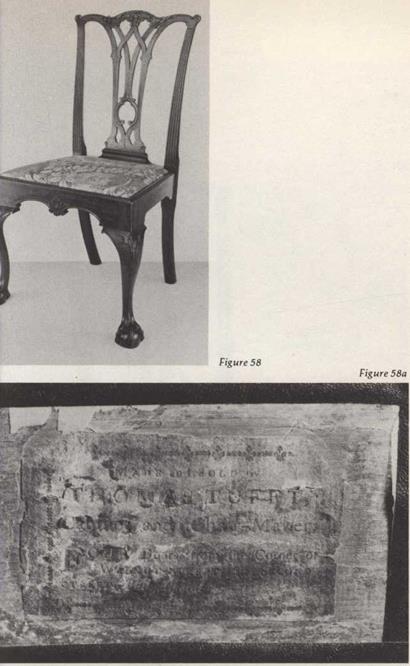

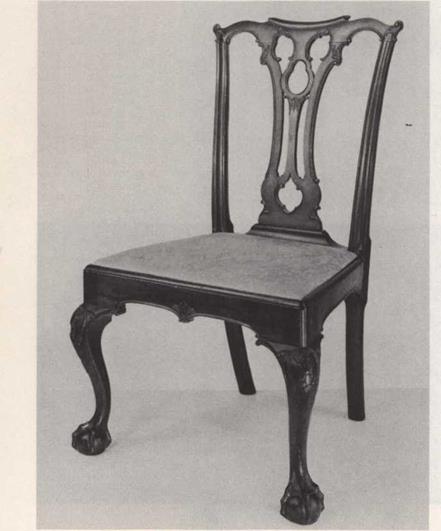

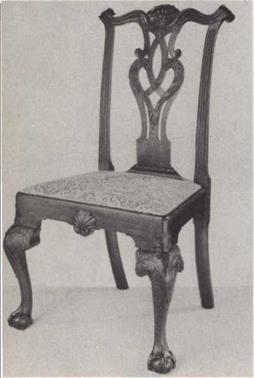

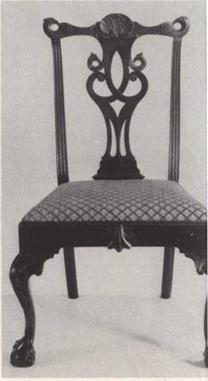

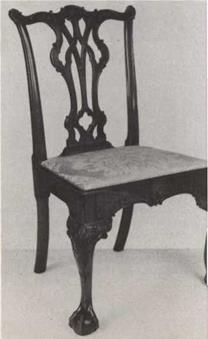

Figures 56,57, and 58.

Side Chairs. Chippendale believed that side chairs looked best when the seats were "stuffed over the rails." A few Philadelphia chairmakers followed the London craftsman’s advice (Figs.

56, 71; PI. IX) even to a double row of brass nails. These chairs have legs and feet associated with Philadelphia construction, but their makers drew freely on Plate X of the Director (1762 ed.) for splat, crest rail, and carving suggestions.

The carved cabochon seen on much Philadelphia furniture is on the pronounced ears of Figure 56. A label (Fig. 58a) of Thomas Tufftfca. 1738-88) appears on Figure 58; but despite its similarity to Figure 57-C-scroll-edged knee blocks, double-arched skirt edged by C-scrolls, central foliage carving on the front rails, and similar knee carving on the front legs—it is unlikely that he made both ■chairs. Fig. 56: mahogany; 1765-80; H 38 W (97.1 cm); no. VI in a set; acc. no. G59.3390. Fig. 57: mahogany; 1760-80; H 38Vs" (97.1 cm); acc. no. 59.3397. Fig. 58: mahogany, white cedar; 1760-80; H 38W (98.7 cm); tradition of ownership by Charles Carroll the Barrister at Mount Clare, Baltimore, Md.; no. VI in a set, one of a pair; acc. no. C57.514.

Figure 57

|

|

|

|

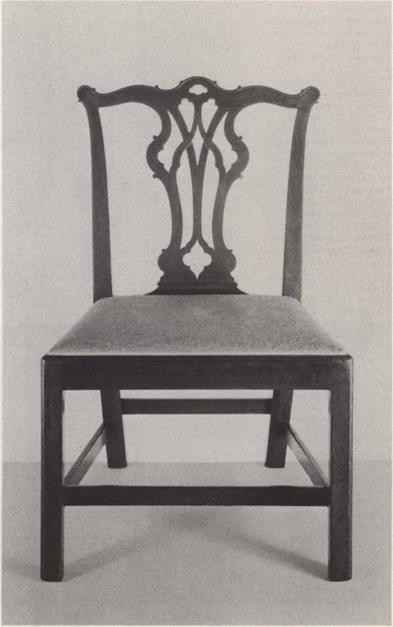

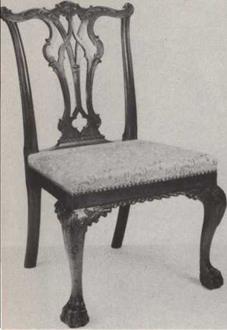

Figures 59,60, and 61. Side Chairs. A chair with a back identical to Figure 59 is in the collection of the late Mitchell Taradash. Bearing the label of James Gillingham, it has given rise to the designation of these chairs as Gillingham-type. Many Philadelphia chairs with identical or similar backs survive (Figs. 39, 60). At least 7 different varieties were illustrated by Hornor, гг Given the complex organization of craft activity in Philadelphia, it is unlikely that all were produced in one man’s shop. Figures 60 and 61 share pierced corner brackets, beaded-edge seat frames and Marlborough legs, and blind-carved fretwork on stiles and crest rails. Their ears, crest rail shape, and splats are quite different. Philadelphia price lists note that "bases and bragetes [brackets] "could be added to chairs. Evidently the old Philadelphia term for what are now called Marlborough feet was bases. Fig. 59: mahogany: 1765-80; H 39" (99.1 cm); no. I in a set, one of six; acc. no. G61.809.2. Fig. 60: mahogany, white cedar; 1765-80; H 3T4s" (96.2 cm); no. Ill in a set; acc. no. G61.1198.

Fig. 61: mahogany, white cedar; 1765-80; H 38’U" (97.1 cm); no. I in a set; acc. no. G61.1196.

![]()

Figures 62, 63, and 64. Side Chairs. Strap splat is a modern term often used to describe the interlaced straps and scrolls that formed another type of back for Philadelphia side chairs of this period. New York (Figs. 1, 5-6,

12), Massachusetts, and South Carolina craftsmen had their own interpretations. But with or without a carved tassel at its center, Philadelphia’s version is distinct because of the attempt to produce an effect of interlaced wood. Cost usually prevented more effort than is exhibited here, but when not limited

by economics, Philadelphia’s artisans could shape this type of splat to its limit (Figs. 68-69). Much carving on Philadelphia Chippendale period furniture has been termed rococo. No matter how rich and florid the carving (Figs. 62-63), however, it is usually balanced and its elements arranged symmetrically. The asymmetrical leaf carving on the front rails of Figures 62 and 64 is, therefore, exceptional both in quality and design. Outstanding features on these chairs include the carved shell or leaf cap

![]()

on the corners of the front seat rail, ears of large carved shells (Fig.

62), and interlaced ribbons of leaf carving on the crest rail (Fig. 63). Fig.

62: mahogany; 1765-80; H 40’As" (101.7 cm); no.

Ill in a set; acc. no.

C58.2262. Fig. 63: mahogany; 1760-80; H 39’k" (100.3 cm); no. Ill in a set; acc. no. C59.1330.

Fig. 64: mahogany; 1760-80; H 39sk" (100.6 cm); name parrish stamped inside back seat rail; no. I in a set, one of a pair; acc. no.

68.88.1.

Figures 65, 66, and 67. Side Chairs. Philadelphia chairmakers produced many variations of the pierced strap splat. By eliminating the interlaced effect and adding carving in the "modern" taste, a back such as that of Figure 67 could be produced. Tassel-and-rope carving emphasizes the curved cresting rail of Figure 65 and eliminates the need for a tassel on its splat. Part of a set (Fig. 41), it was among the presidential furnishings of George Washington’s residence in Philadelphia,23 Bird-head carving is usually found on armrest terminals of New England or New York chairs (Fig. 1). In Figure 66, a rare variation of the interlaced strap splat, carved bird heads replace the usual volutes, shells, leaves, or cabochon for ears of the crest rail and also replace the usual volutes in the splat. All three examples have fluted stiles and shell carving centered on the cresting and front seat rails. Fig. 65: mahogany; 1765-85; H 41V (106 cm); no. VI in a set, one of two, formerly a set of 5; acc. no.

G58.2258. Fig. 66: mahogany, yellow pine, tulip; 1765-80; H 39V (101 cm); acc. no. 53.171.2. Fig. 67: mahogany; 1760-80; H 39V (101 cm); acc. no. G59.1327.

|

|

||

|

|

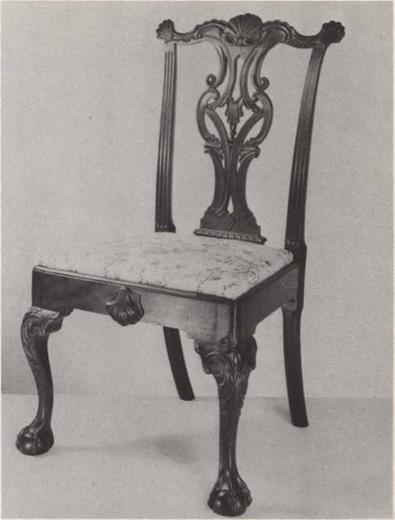

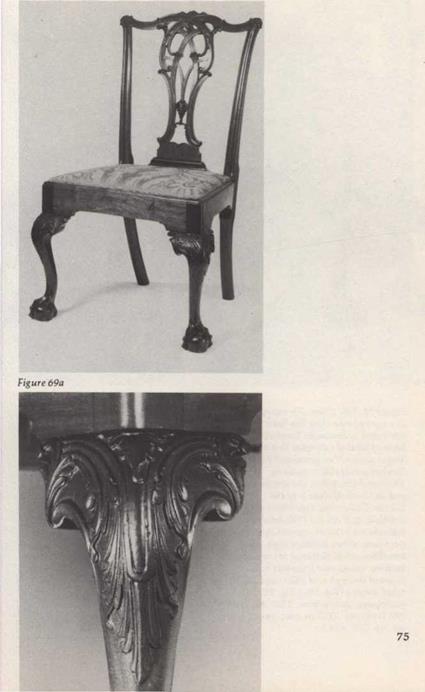

Figures 68 and 69. Side Chairs. Two of the finest colonial American side chairs, both have their design source in Chippendale’s Director (1762 ed., Pis. XVI and IX). Figure 68 is similar to an armchair at Winterthur (Fig. 45) except for the carving on its stiles (Fig. 68a) and legs. It is related to a set of chairs made for John Dickinson, illustrated in Hornor’s Blue Book. Figure 69 may be one of a set of chairs made for Thomas Fisher of Wakefield.24 It relies for its success more on an illusion of interlaced wood in its crest rail and splat than on carved, natural ornament. The carved husk on its splat and its knee carving (Fig. 69a) indicate the skills possessed by Philadelphia woodcarvers. In 1770, 6 chairs like Figures 68 or 69 might cost as much as a desk and bookcase. Fig. 68: mahogany, white cedar, yellow pine; 1760-75; H 37%"

|

(95.9 cm); one of four; acc. no. G52.240.3.

Fig. 69: mahogany; 1765-80; Н39 "(99 cm); no.

VI in a set; acc. no. 56.41.1.

|

|

![]()

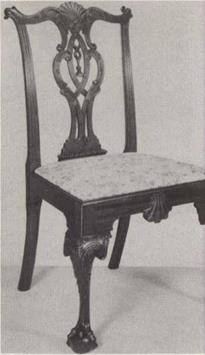

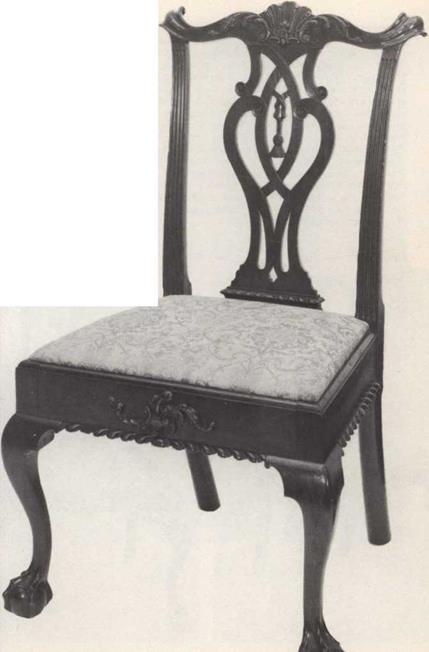

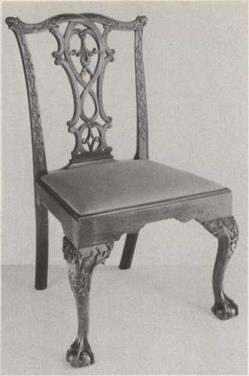

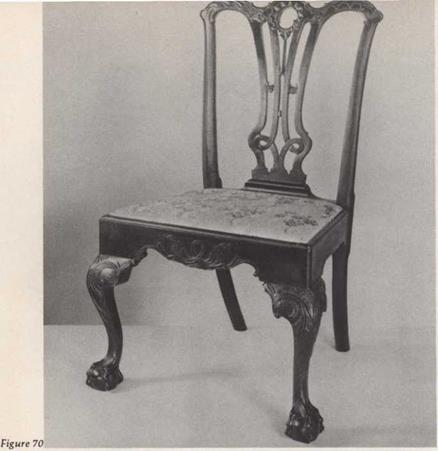

Figure 70. Side Chair. For many years this type of side chair has been attributed to Benjamin Randolph on the basis of labeled examples that are no longer accepted as genuine.25 Hornor illustrates side chairs made by Thomas Affleck that use similar backs and an identical chair is in the Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.26 All the Philadelphia features are present—carved claw with deep concavities between high-relief knuckles; a ball flattened at top and bottom; stump rear legs; side rails tenoned through rear stiles; and high – relief carving (Fig. 70a). Fig. 70: mahogany, yellow pine; 1765-80; H 394в" (99.3 cm); no. ХПП in a set, one of four; acc. no. G61.803.3.

Figure 70. Side Chair. For many years this type of side chair has been attributed to Benjamin Randolph on the basis of labeled examples that are no longer accepted as genuine.25 Hornor illustrates side chairs made by Thomas Affleck that use similar backs and an identical chair is in the Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.26 All the Philadelphia features are present—carved claw with deep concavities between high-relief knuckles; a ball flattened at top and bottom; stump rear legs; side rails tenoned through rear stiles; and high – relief carving (Fig. 70a). Fig. 70: mahogany, yellow pine; 1765-80; H 394в" (99.3 cm); no. ХПП in a set, one of four; acc. no. G61.803.3.

Figures 71 and 72. Side Chairs. It was noted (Fig.

47) that as early as 1772, Peter Manigault may have introduced this type of chair to America from England. In 1783, Martha Washington purchased 24 “Table Chairs," with backs quite similar to Figure 71, as she passed through Philadelphia.17 The name Peter Kline, branded under the back seat rail of Figure 71, is probably that of a bricklayer listed in Philadelphia from 1797 to 1882. Daniel Trotter (1747-1800) is the Philadelphia cabinetmaker associated with chairs like Figure 72.28 Fig. 71: mahogany, hickory, white pine, white oak, tulip, walnut; 1780-1800; H 37W (95.7 cm); acc. no. C59.1487. Fig. 72: mahogany, yellow pine; H 38%" (97.5 cm); acc. no. G57.871.1.

|