THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

INTRODUCTORY

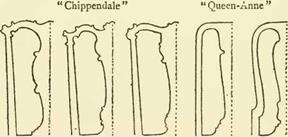

The task of tracing, identifying, arranging in chronological order, and placing on record the scattered fragments now available of the history of such English furniture and woodwork as was designed and manufactured prior to the commencement of the seventeenth century, is, for many reasons, beset with difficulties; indeed, it is greatly to be feared that the story, in absolute entirety, will never be told, for the requisite material upon which to base it is no longer available. In the first place, the cabinet makers of the earlier times did not cultivate the practice of publishing design books, or illustrated sheets; if they did, none has survived to tell the tale. Later on, when we arrive at the “ Chippendale ” period, all is delightfully plain sailing for the historian, but when dealing with work of an earlier date we have to grope about, so to speak, in greater or less obscurity; piecing together as well as may be fragments of the story gathered here and there, so far as circumstances will permit, in order to arrive at an approach to the truth, and be in a position to form a fairly just estimate of the whole. These fragments are comparatively few and far between, particularly when we get back to the reign of Elizabeth —as is, of course, only natural ; for it needs good craftsmanship indeed to survive the wear and tear of over three centuries. Yet, to the lasting credit of the old woodworkers be it

said, much not only has remained even to the present day, but still appears to be “ good" for a few centuries more. Only the “ fittest," of course, has survived. This aspect of the question must be emphasised, as not a few people seem to lose sight of the fact altogether, and draw erroneous conclusions, which they express loudly, in consequence. Critics from whom better things might reasonably be expected are frequently heard comparing the work of the so-called u good old days ” with that of the modern craftsman, greatly to the disparagement of the latter.

The favourite plan adopted by these “ superior" people is, in the first place, to take some of the masterpieces of days gone by, upon the execution of which neither loving labour nor expense was spared, and place them side by side with commercial productions of the present day, designed and made under modern conditions, and for a totally inadequate rate of remuneration. Having done this, they wag their heads, and enquire :—“ Where is your modern craftsman now? ’’ Personally I think that he comes out of the comparison very brilliantly indeed. If the greatly-belauded cabinet maker of the sixteenth, seventeenth, or even eighteenth century were placed in the position of his twentieth-century successor, compelled to “cut prices," as the trade term it, and to hold his own against the keenest competition on every hand, which will allow him but the barest living ; what would be the result?

In the name of all that is just and fair, let us be honest enough to look the situation squarely in the face. As a matter of fact, I have no hesitation in contending that many a piece of furniture which may be purchased nowadays for a few sovereigns in the showrooms of, shall I say, the much – abused and extensively patronised Tottenham Court Road, is in very truth, considering the money expended, of far greater value than some of the most beautiful and costly creations of earlier times. And let it be recognised and remembered that we have in our midst now designers and craftsmen as gifted in all respects as any the world has ever seen. Given the opportunity, these men are fully capable of designing and executing work which would rival, and probably surpass, the finest productions of any age or country, but—and there is that awful “but"—it is the opportunity, and not the genius, which is wanting. The days when artists—I am speaking now of those who devote themselves to the applied arts—enjoyed the generous, indeed lavish, patronage of such men as Lorenzo di Medici, or the recognition and support of the State, as in France during the reign of Louis the Fourteenth, are past and gone—it would almost seem for ever; and both artist and craftsman, as well as art and craftsmanship, suffer as a natural consequence.

It will be well for us, then, always to bear in mind the fact that, with very few and unimportant exceptions, it is only the best and therefore most expensive work of the past which has survived for so long a time ; and that such furniture as adorned the homes of the poorer, and a considerable percentage of the middle, classes has gone to the wall long ago.

With regard to the sixteenth and seventeenth century furniture of our own land especially, it must not be forgotten that the history of the times during which it was designed and manufactured literally teems with records of wars and rumours of wars. This makes it perfectly clear to the thoughtful student that the condition of affairs then generally obtaining was not conducive to the cultivation of the arts of peace. Indeed it is astonishing that so much has survived as is now to be found in our national museums and private collections. How far the existence of this state of continual political and social unrest is reflected in the forms and general character of the furniture and woodwork of the period concerned we shall discover later, when we come

to consider individually the pieces illustrated by way of example.

Of furniture proper, that is to say portable articles such as tables and chairs, dating from the reign of Henry the

|

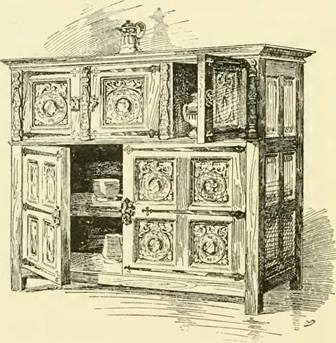

Henry-the-Eighth Armoire (Now in the possession of Mr. J. Seymour Lucas, R. A.) (See below for reference). |

Eighth, actual and authentic specimens are all but nonexistent ; our knowledge, therefore, of the household gods of that time must, for the most part, be acquired from ancient books and prints. But I am fortunate in being able to illustrate one piece, the authenticity of which is not open

to question—a Henry-the-Eighth armoire, now in the possession of Mr. J. Seymour Lucas, R. A. This is thoroughly “ Francois-Premier ” in character, and it is most probable that the carving was actually designed and executed by French artists and craftsmen, but the construction is undoubtedly English. Mr. Lucas discovered this example in an old farmhouse, where it was used for the storage of cheeses, and fifteen years elapsed before he could induce the owner to part with it. Yet he persisted, and in the end secured the treasure. It is true that, in spite of determined purification and fumigation, the cupboards are still redolent of cheese, but that is a small matter under the circumstances.

It is not, however, my present intention to go back to so early a date. Our study will seriously commence with the style prevailing at the end of the reign of Elizabeth, with the period when what has become known as the “ Elizabethan " was at its zenith, and almost on the eve of that transition which finally resulted in the evolution of the “ Jacobean.”

It is hardly necessary for me to say that the “ Elizabethan " in architecture did not actually attain its highest development until about the year 1607, when King James the First was on the throne. It is, therefore, in the stately homes erected or completed at the time when the rule of the Stuarts was commencing that we find the style at its best, and interpreted by men of the calibre of John Thorpe and other eminent contemporary architects. Of these old residences but few remain in their entirety : those which have successfully withstood the ravages of time and escaped the tender mercies of the destroyer are, however, sufficient to enable us to gain a glimpse of the dignity and splendour of the internal architectural woodwork of the houses in which the “Upper Ten” of the days of “Good Queen Bess ” were wont to live. On the other hand, examples of genuine Elizabethan movable furniture are extremely rare and difficult to find. Those who possess any

may deem themselves fortunate indeed, and are entitled to crow—to use a colloquialism—over the vast majority of their fellow-collectors.

The growth of the “Jacobean” out of the style which immediately preceded it was very gradual, and commenced with small beginnings; hence, in its earlier forms, it is sometimes not easy to distinguish the offspring from the parent, so closely do they resemble one another. Not a few important characteristics remained for a lengthy period common to both styles, with the inevitable result that, when studying the two, much confusion may arise, and considerable knowledge of minuter details is required to enable us successfully to get over the difficulty. In apportioning the various phases of these styles to their proper periods, we are guided, however, to a certain extent, by the commendable practice of some of the old wood carvers of dating their works. The figures, as we shall see presently in our illustrated examples, frequently are cleverly interwoven with, and so made to constitute a part of, the carved and inlaid enrichment. A similar course, I need hardly say, was followed by the old Moorish decorators, as exemplified in the incomparable Alhambra, and elsewhere in Spain and Morocco. Genuine examples of English sixteenth and seventeenth century furniture in which this occurs, it is true, are not very numerous, but a few are extant, and they aid us considerably in arriving at a decision as to the approximate dates of other pieces similar in character but not so distinguished.

Speaking generally, most of the seventeenth-century British furniture which now remains to guide us in our studies is of oak; but it by no means follows that oak was the only wood used by the cabinet and chair makers of those days in the pursuance of their crafts; walnut, ash, elm, beech, chestnut, and other woods were also extensively employed. It was the oak, however, which proved to be

most fitted to "brave the battle and the breeze,” and defy the ravages of centuries, in the home as on the "rolling wave ” ; while the less enduring productions of the forest and woodland have long since given way before the strain imposed upon them. Chairs, and not so frequently, tables, are occasionally to be met with in the less durable woods, but these are almost invariably either in a state of extreme dilapidation, or else have been " restored ” out of all recognition of their former selves, leaving but little of the original structures to tell the tale.

Of the series of styles with which I shall endeavour to deal in these pages, those which had rise during the century now under consideration present, on the whole, perhaps, the least difficulty as regards general classification ; but to give to each its proper place is not nearly so simple. Still, I think, and hope, that a careful study of the accompanying types, and of the special peculiarities and characteristics of each, will enable the reader to obtain such a knowledge of the subject as will materially assist in the removal of many obstacles which might otherwise lie in his path.

We might reasonably imagine that the whole of the woodwork—furniture, wall-panelling, etc.—of the " Elizabethan,” as of other periods, would partake, to a very large extent if not wholly, of one and the same character, constituting one more or less harmonious whole. That, curious as it may appear, was not by any means the case. A certain degree of relationship is apparent, of course, between the various examples; but, notwithstanding that, a very considerable difference is to be recorded. Broadly speaking, the architectural woodwork of the " Elizabethan ” is marked by a far greater refinement and more perfect execution than is the furniture of the same period, which partakes of a more rugged character; though there are occasional exceptions to this rule. Those exceptions, however, were only to be found among the household gods designed and made for the

wealthier patrons, and cannot in any sense be accepted as representative of the art or craft of the age.

In studying the furnishing of the homes of this period, we must be careful, at the outset, not to forget the fact that, during the early part of the seventeenth century, the great majority of the people, the “masses" as they are glibly termed nowadays, subsisted and worked under conditions vastly different from those which prevail in the present day. We must remember that even the average modern “ desirable villa residence,” imperfect as it may be in our estimation, would have been regarded by the bourgeois of the time of James the First, and of his immediate successors, with feelings not far removed from awe, and the admiration excited by what to them must have seemed models of comfort and convenience would have been unbounded. In those days the family of small means did not rejoice in the possession of separate and distinct dining and drawing rooms ; and such a thing as a “spare bedroom," that joy of the newly-wedded wife, was a sign of opulence indeed. Then, the single apartment, which, be it noted, was not by any means too commodious, was requisitioned to serve many purposes, except, of course, in the homes of the well-to-do; even with the majority of the upper middle classes accommodation was none too generous. Thus it came about, in the natural order of events, that little attention was lavished upon any apartment other than those devoted to sleeping, to the entertainment of guests, and the enjoyment of the “kindly fruits of the earth " ; it is, therefore, to the old bedrooms and living-rooms that we must look first for the most typical examples of the furniture in common use during the period in question.

It will be apparent then, I think, that it is quite impossible to classify most of the pieces of furniture of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as having been designed and manufactured for exclusive service in anyone particular room, such as the drawing-room, dining-room, bedroom, hall, library,

or study, as can be done with the majority of the productions of a later date. They had practically no definite abiding place, but were shifted from one part of the house to another, as occasion demanded, and even from one residence to another when protracted visits were being paid. Of this aspect of the subject I shall have more to say in due course.

Recognising also the fact that much of the furniture now in everyday use is quite modern in origin, so far as form and general appointments are concerned, and having discovered that many articles which are now regarded as necessities were quite unknown to our forefathers of two centuries ago, it is more than a little interesting to endeavour to discover what occupied their places in the early days, and to see how far the requirements of the household were fulfilled by the comparatively few predecessors of the thousand-and-one objects which are now to be found in almost every furnishing showroom throughout the country.

Before, then, entering upon a detailed examination of the individual examples which I have selected for illustration on the plates which are to follow, I will enumerate the chief pieces with which the collector is likely to meet nowadays, dating from the “ Elizabethan ” period.

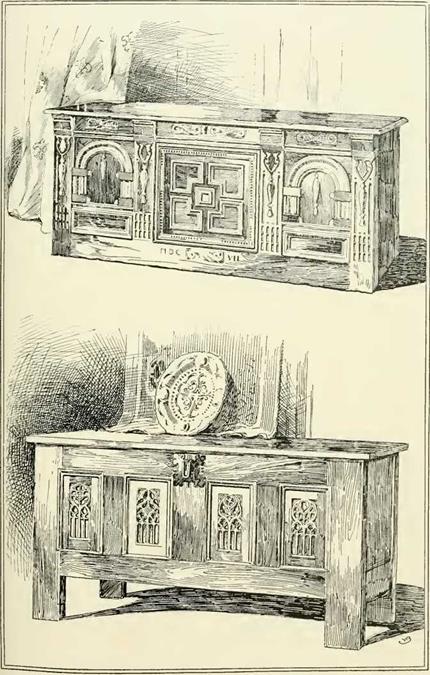

First and foremost come chests or coffers of many sizes, shapes, and descriptions; and the extensive variety to be met with even to-day in all parts of the kingdom, of unquestionable authenticity, is proof conclusive that they undoubtedly ranked among the most important and indispensable accessories of the English home from the very first institution of the art and craft of the cabinet maker. They ranked next in importance, that is to say, to the beds, tables, and seats of one kind or another, which supplied the requirements of bodily repose and the appetite.

It is not by any means an uncommon thing for writers to assert that the old English chest was the direct descendant of, and inspired by, the gorgeous Italian marriage coffers, or

cassoni, of the Renaissance. Such a statement is certainly not altogether correct, for we must go much farther back to discover their origin. The cassoni, indeed, were themselves nothing more nor less than glorifications, for special occasions, of a piece of furniture known and used, ages before the Renaissance was dreamed of, by all classes who possessed any furniture at all; and if we want to trace them really to their source we must search the records of those days when solid trunks of trees were "scooped out," more or less clumsily, in order that they might be utilised for the required purposes. One such is standing within a few feet of me as I write these lines.

The chest, like the chair, table, and bed, was, in the first place, the outcome of an absolute necessity. Provided that it satisfied the requirements which called for its construction, little or no thought was originally devoted to making it graceful or in any way decorative. Convenience, strength, and security were the first considerations to be borne in mind. It was obvious that clothes, when they came into general use, had to be stored somewhere, and when once the ball was set rolling, the steady development of fashion in wearing – apparel called for ever-increasing accommodation. With the growth of civilisation the smaller appointments of the household also increased and multiplied ; and, little by little, things which were once regarded as luxuries, unattainable by most people, found their way into nearly every home, and finally came into vogue as articles of constant and everyday use, whose services could not be dispensed with by anyone. Apart quite from the adornment of the body—by no means an inconsiderable matter as time went on—the loom was set to work to enhance the comfort of the bed chamber and beautify the table; and the increase of household linen of every kind and description provided another reason for the devising of convenient and safe receptacles for such domestic treasures. Further, the taking of meals came to be re-

garded as something more than the mere unavoidable consumption of food for the sustentation of the body. Dinner, particularly, developed into an important function, at which friends might be fittingly feasted upon the “fat of the land," where good-fellowship could reign supreme, and at which brilliant intellects, pitted one against another, might furnish that “feast of reason and flow of soul"—too often, it has been said, a “ flow of bowl ”—which elevated the mere meal into a feast in every sense of the word. This, of course, rendered it essential, or at least desirable, that the appointments of the table should not only answer the demands of strict utilitarianism, but at the same time should be of such a character as to give pleasure to the eye. Knives, forks, spoons, dishes, plates, and glass commenced to receive the attention of artists and craftsmen of the highest renown. The simplest implements and utensils, which formerly could lay claim to the possession of but small decorative value, or indeed of any value apart from their utility, for they were originally fashioned from the commonest and least expensive materials, were produced in rare and costly metals, wrought and enriched with the greatest taste and skill that influence and money could command. The family plate was raised to a position of rare honour and importance, and was proudly regarded as one of the most cherished possessions of the old English home. Most of this, also, had to be kept in safety somewhere, and here, once more, the chest was welcomed as a satisfactory solution of the problem. In view of all these many and varied demands, it is not surprising that the design and manufacture of that piece of furniture occupied no small part of the time and attention of the old woodworker.

It is certainly not easy for the twentieth-century housewife, who has at her command fire and burglar proof safes, steel and iron jewel caskets, wardrobes, linen presses, chests of drawers, roomy cupboards, box rooms, closets, cabinets, sideboards, and other similar receptacles, devised by modern

ingenuity, to appreciate all the difficulties with which the lady of the seventeenth-century house had to contend, or to understand by what means she could possibly overcome them.

The question “where to put things” has ever constituted a problem most difficult to solve for those of our women folk who are endowed with a love of tidiness, and who would be so bold as to assert that there exists any woman who is not so endowed? So generally is this recognised, that, as time goes on, architects strive more and more earnestly to provide in their houses the greatest possible number of cupboards in the smallest possible space, while the designer of cabinet work racks his brains to satisfy his prospective lady clients in the provision of shelves, brackets, drawers, pigeon-holes, and every other description of hole, corner, and recess which it is possible to imagine and devise. Yet, with all the ingenuity that they can bring to bear upon the matter, the task of giving perfect satisfaction seems to be as far from actual accomplishment as ever.

To return to the “ Good old Days.” The necessity for conveniences and accommodation of the class I have indicated was by no means so great as it is now. Tastes were more simple and less exacting; it was far more easy, therefore, to satisfy them. The same difficulty, nevertheless, certainly did exist then, though in a lesser degree, and the manner in which it was overcome brings us back to the chest or coffer pure and simple. We shall presently mark the most characteristic forms which it took in its earlier stages, as well as make a point of noticing the manner in which it blossomed forth into something far more imposing than the unpretentious rectangular box which was the earliest ancestor of the whole tribe. For the moment we have come to the conclusion that this piece of furniture, in its various forms, was in great demand, and was, in consequence, extensively manufactured ; it is not, therefore, surprising to find that examples

13

of it rank among the most numerous of the relics now existing of the days to which they belonged.

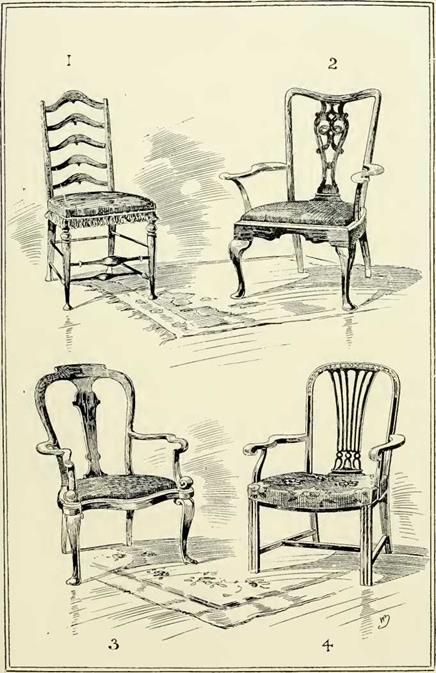

Next in number and importance come seats and chairs, articles of a type more indispensable, of course, than the chests themselves, as it is obvious that we must sit or lie somewhere, whatever may become of our various and sundry impedimenta.

Continuing the list we have sturdy side-tables, developing later into u court" and “ bread – and – cheese " cupboards, “bahuts,” and “ armoires"—ancestors to the sideboard of to-day, though so vastly different in form and character; smaller tables—rectangular, circular, hexagonal, and octagonal, and in some cases so contrived as to fold up ; and last, but by no means least as far as general proportions are concerned, four-post bedsteads.

Other pieces not included in the foregoing list may be discovered occasionally here and there, but they are exceptions, and, as such, will not enter very largely into our calculations.

I have contended that the earnest and well-informed student of the furniture of days gone by cannot fail, if he pursue his studies in the proper vein, to find clearly expressed in the examples with which he has to deal more than a slight indication of the different spirits pervading the ages in which they were produced; and, indeed, it is difficult to see how it could be otherwise. This contention is, I am well aware, far from being a novel one, but the fact is not as generally appreciated as it should be, and I am perfectly confident that, were it more fully realised and strenuously insisted upon, many more people would be inclined to pay greater attention to a study the pursuit of which positively teems with interest and delight.

Owing to ignorance—not necessarily intentional ignorance —the subject is regarded at present by some as an unpleasant and incomprehensible u craze" for raking over and “rum-

maging” among objectionable, dusty, and worm-eaten stuff, which in their estimation should long ago have been relegated to the dustbin, or have been chopped up for firewood.

We are told that there are sermons in stones. If that be so, and unquestionably, if accepted in its proper sense, the statement cannot be refuted, surely there is many a story “ writ large " in the household gods of our forefathers. Nay, their actual tastes and habits may be judged to a far greater extent from their furniture ; for their places of abode—the eloquent stones of architecture—were, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, planned and built quite independently of any consideration of the individual preferences or requirements of their possible occupants. On the other hand, their internal environment, the furniture and woodwork with which they were to be surrounded, was of their own seeking and selection, and it is to be presumed that they made a point of acquiring that which appealed most strongly to their ideas regarding what should be, so far at least as the means at their command would permit. If this view of the matter be accepted as correct, it is not too much to claim that a people, or an age, may, to a very considerable degree, be judged by the furniture and woodwork appertaining to them.

Regarded in this light, the study of these old chests and tables, beds and chairs, is veritably fraught with romance. They become animated, and talk with us of times, manners, and customs long since gone by, and almost forgotten ; and we see grouped around them the giant shadows of men and women who have made history, as well as those of the quiet family circle, drawn cosily round the homely ingle, whose deeds, it is true, have never been handed down to posterity, but who, nevertheless, played their part in the great game of life.

The inclination to enlarge upon the romantic side of old furniture collecting is great and hardly to be resisted, but I must not give way to temptation here. I must content myself

with simply indicating that the romantic side really does exist, and with assuring the student that it will reveal itself more and more fully the greater and more devoted the attention he accords to the subject. Regarding in this light the work of the period with which we are now dealing, we naturally endeavour to discover what kind of story it has to tell us, apart from the mere interest derived from the artistic and technical view of its design and construction ; and we attempt to trace, in its lines and enrichment, something of the history and conditions of the people who made it, and for whom it was made. What is its general character, and what can we read in it? Sturdy, often-times to the point of clumsiness ; obviously constructed to withstand the hardest of usage, and defy Time the Destroyer; made in one of the hardest woods obtainable; it is enriched, it is true, with carving and inlay, but in a manner which is comparatively primitive, and there is every indication in these late “ Elizabethan " and “Jacobean" chairs and tables that the age in which they were made was not in any way notable for the cultivation, encouragement, and consequent development of the arts of peace. I need hardly say that the impression which they convey in that respect is in no way misleading. Time and again the country was embroiled in strife for the support or overthrow of one cause or another. The kingdom was split into factions, blown hither and thither, as one or the other party gained the upper hand ; men, and indeed members of the same families, erstwhile the closest of friends, became the bitterest of enemies in consequence of the views which they severally entertained respecting the question of home government.

The old saying, “ An Englishman’s home is his castle,” was something more than a mere figure of speech in those days, suggesting possible invasion and defence of its rights and privileges. No man then knew when he might be called upon to protect himself, his family, and his goods from the raids constantly being planned and carried out by political

opponents, and which resulted by no means infrequently in bloodshed, and almost invariably in the destruction or loss of’ property.

Living under such conditions as these, and finding it absolutely necessary to be prepared for the worst, knowing not what any moment might bring forth, it is hardly to be wondered at that our forefathers regarded existence as a stern reality, and had but little time, whatever inclination they may have possessed, for the acquisition of those graces and refinements which go to make life beautiful. They were to follow in after years.

Everything with them was uncertain, from personal safety to the security of every penny they possessed ; and they were compelled to adjust themselves to their political and social environment, and deport themselves accordingly. It is not necessary for me to dip further into a period of English history the records of which will be fresh in the memory of all who peruse these pages, except to point out, here and there, how certain changes in the government and condition of the people influenced, and are consequently to be traced in, their home surroundings.

One of the first points to be noted in connection with early Jacobean furniture is that plain, straightforward, and simple construction is its principal characteristic, and that under no circumstances is undue elaboration of general form to be expected. If found, it must be classed under an altogether different heading, as hailing from some other country, or dating from an entirely different period of time.

I insist upon this, as I am writing, for the moment, of form alone, as entirely distinct from enrichment of any class or description—a phase of our subject that will be dealt with at length in its proper place.

Regarded, then, simply as examples of construction, the cabinet work, almost without exception, is such as might have, and probably very often did, come from the bench of

the skilful and conscientious carpenter, so primitive is it and entirely free from those constructional problems the solution of which was imposed upon the cabinet maker by designers of succeeding centuries. By way of illustrating this statement, let us take the chests, to which reference has already been made. Many, indeed the majority, of them are but little more than simple rectangular boxes, strongly put together, varying only so far as size and relative proportions are concerned. Some are raised slightly from the floor, say from three to nine inches, and supported by a roughly turned sphere of wood, a square leg, or a continuation of the end framework ; and some rest flat upon the floor itself. Whatever claim these might make to the possession of decorative value—and many of them, as we shall presently see, certainly did possess that quality—must be credited not to the skill of the craftsman responsible for the “ carcase," as the main body of any piece of cabinet work is technically termed in the trade, but to that of the carvers and inlayers who, when the “ carcase " was completed, and ready to be put together, were called in to enrich it to the best of their ability and so far as considerations of cost allowed. So much for the moment for a brief summing-up of the leading characteristics of the forms of Jacobean cabinet work.

Now a word or two, by way of introduction, respecting the enrichment. This, I need hardly say, was, at the inception of the style, more than a little hybrid in character, partaking to a certain extent of the late “ Elizabethan,” and even, not infrequently, awakening memories of the Gothic, which “died hard.” Notwithstanding the energy displayed by the pioneers of the English Renaissance to kill, or, at all events, supersede the traditions of the Middle Ages by the introduction into the furnishing of the home of what was in those days a “New Art,” the Gothic was not to be despatched at a blow. After the lapse of many a year, the old “ linen” and “parchment” panels, originated by,

Б

and beloved of, the ecclesiastical carvers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, still put in an appearance, though amidst strange surroundings ; and we do not seem to tire of them. They are often accompanied by other decorative detail, the origin of which dates from the days when the carver more often than not found his training in, or under the shadow of, the monastery. This is so all through the “Elizabethan," and far into the “Jacobean” era.

Yet “Jacobean” detail in its purest phases was neither entirely new nor in any way revolutionary; it must rather be regarded in the light of a crude attempt on the part of the British carver to follow in the footsteps of the foreign craftsmen brought over to this country during previous reigns by the command, and under the patronage, of royalty. This is a point that must not be overlooked. Proud as we may be of the position we have won among the nations of the world in relation to the cultivation and development of the arts and crafts, we must by no means ignore the fact that, in these early days, not to speak of more recent times which will call for our consideration later, we depended very largely, not only upon foreign inspiration, but upon the actual presence in our midst of foreign artists and craftsmen themselves. If we look for a moment at the inlay, carving, and decorative painting produced in this country during the reigns of Henry the Eighth and Elizabeth, we shall see that nearly all the finest was from the hands of skilled artists, neither born nor trained upon British soil, but induced to work here for a time at rates of remuneration almost princely in their generosity. It sometimes happened, as a matter of fact, that more than one royal patron of the arts was endeavouring to secure the services of the same man at one and the same time, and it was only natural that the highest bidder should gain the day. At all events, they had to be induced to come somehow, and at almost any price.

These men were born and bred in countries where art seems to have been in the very air, and where, too, the most generous, nay, more than generous financial encouragement of art in all its phases was not lacking. Small wonder that men saturated, so to speak, by the very atmosphere of the Italian and French Renaissance; men who had played leading parts in making those styles what they were ; absolute masters of design and craftsmanship, and artists by birth, to their very finger tips, should be in demand; and we may feel thankful that we are so fortunate as to enjoy some, at least, of the fruits of their genius. They came over to show what they could do, and set an example for us to follow, if we could. But to admire was one thing; to follow quite another. The rare and perfect mastery which they possessed, and which, in a great degree, was a national as well as a hereditary gift with them, was not to be acquired by the conservative Briton in a day—far from it! He did his best, doubtless, so far as his temperament and the conditions under which he lived and worked would permit; but it was an insignificant best at the most. Sympathetic and lenient as we may be, and naturally are, through national pride, we cannot fail to recognise the many shortcomings in these early attempts to copy a style, or rather styles, which were altogether foreign to our nature. We might almost say of the British carver of that period that, for no inconsiderable time, he was floundering about in strange waters which were altogether too deep for him, and in which it was as much as he could do to keep afloat at all. The result was that he produced a sort of debased “ Renaissance" which, though effective in its way, we cannot but admit was vastly different from, or, as some say, nothing better than a weak caricature of, the originals which had come to life under the sunny skies and amid the rarely beautiful natural surroundings of Italy and France.

The “Elizabethan” and “Jacobean” were almost entirely devoid of all the romance, fantastic spirit, and extraordinary brilliance associated with the parent styles—the outcome of the temperaments of those responsible for their origination. They were, on the other hand, stamped with the mark of a rugged honesty of purpose created by, and characteristic of, the stern needs of our forefathers of the days of the Armada, of “ Marston Moor,” and a hundred other memorable conflicts ; men made in a different mould from that of their masters in art and craft, and but little disposed to change their nature. They were, of course, quite prepared to buy furniture, as it was an absolute necessity ; and were not averse to the expenditure of some time, labour, and expense upon its embellishment, provided that the cost were not too great. But what they did have must needs be of a sensible and enduring description, such as would fully please their tastes and satisfy all their requirements ; furniture not made for show alone, but designed and constructed to bear the brunt of stern times, when practical utility and lasting qualities were held in the highest esteem, and graces, whether of manner or adornment, played a secondary part.

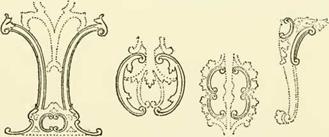

I have had the temerity to assert that Jacobean decoration, particularly carved and inlaid decoration, was practically a debased version of the Italian “Renaissance” and “Elizabethan,” and a brief comparison of the ornamental detail of the three styles will furnish ample proof that this assertion, bold and sweeping as it may appear to be, has foundation in fact. Let us consider first, for example, the crude, ill-drawn, and roughly-carved, though effective, foliations so commonly employed in the first-named, and we shall discover at once that they are in reality neither more nor less than a sort of school-boy attempt to copy the sparkling and piquant leafage, with its graceful sweeps, scrolls, and delicate veining, of the “Cinque-Cento.” They bear a closer resemblance to our common cabbage than to the sprightly

acanthus and similar natural forms whence the Italians drew their inspiration. The successions of circles also, sometimes separate and distinct one from another, sometimes interlaced so as to form a connected and continuous repeating pattern, with and without rosettes or other decorative filling in their centres, such as we constantly meet with in the carving of this period, are, beyond any possible manner of doubt, descended from the old Roman guilloche. They were most probably introduced so frequently owing to the fact that they were easy and cost but little to execute, and required nothing more than a slight knowledge of the use of the compasses in the “ setting-out.” Yet, at one and the same time, they furnished an expeditious method of filling awkward spaces most effectively.

Next we find the familiar “nulling,” freely used in cabinet work of the more costly and elaborate class—a feature which hails direct from the Italian—and many other details from the “ Cinque-Cento,” “ Francois-Premier,” “ Henri-Deux,” and “ Flemish,” undergoing a strange metamorphosis when transported from all the associations of the vineyards and sunshine of their native lands to be interpreted by devotees of the strong beer and roast beef of Old England. But having taken a general review of the period with which we have to deal just now, it will, doubtless, prove to be far more satisfactory if we discuss all these points in connection with illustrated examples of the various phases and details referred to, and this we will at once proceed to do.

Now that we have completed our general survey of the influences at work to render the English furnishings of the greater part of the seventeenth century what they ultimately became, it is time that we should analytically examine representations of typical examples, which will enable the reader to acquire sufficient knowledge of the form and detail portrayed to decide, without any great degree of hesitation or difficulty, as to the approximate date of any old piece belonging to this period. To the “ Elizabethan ". we shall look first, making that the starting-point for our studies.

Those who still retain sufficient recollection of their schooling to recall the fact that their cordially detested “dates" included the item, “Queen Elizabeth, 1558-1603," will, if they have followed the preceding pages carefully, deem it somewhat strange that I have classified this style with those of the seventeenth century. I will, therefore, recall the fact that the “ Elizabethan " did not attain its full development until after James the First had ascended the throne. It is, of course, true that the style was originated during the earlier reign, and, indeed, was assiduously cultivated in the days of the “Virgin Queen," but it was then young, and had not had time to arrive at full maturity.

I have explained that of furniture actually designed and made prior to the commencement of the seventeenth century, comparatively little remains, and what has been handed down to us in any state of preservation is most jealously guarded in a few private collections, and in national museums. Any aspiring collector, therefore, who entertains the hope of encountering specimens in out-of-the-w^ay dealers’ shops or

22

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

|

|

auction salerooms may regard himself as almost inevitably doomed to disappointment. Even to the vast majority of students they are equally unavailable. As a natural consequence, most of us must rest content to note the lines of this furniture from such pictorial illustrations as we may be able to obtain, and even they are few.

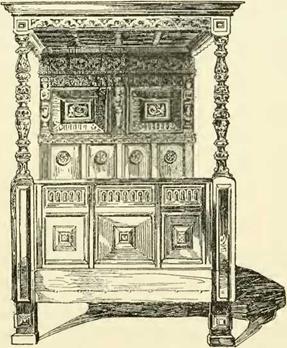

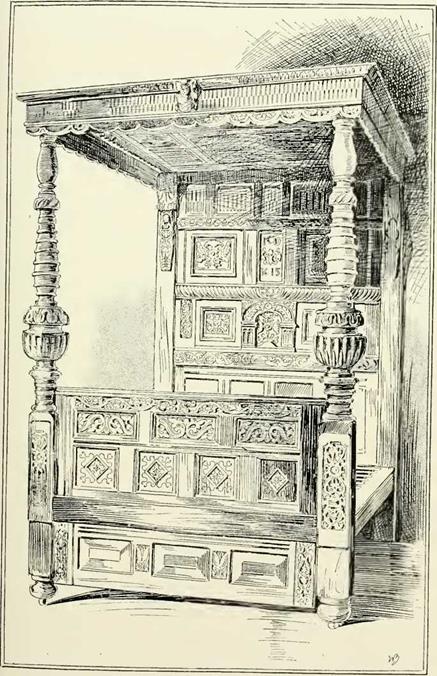

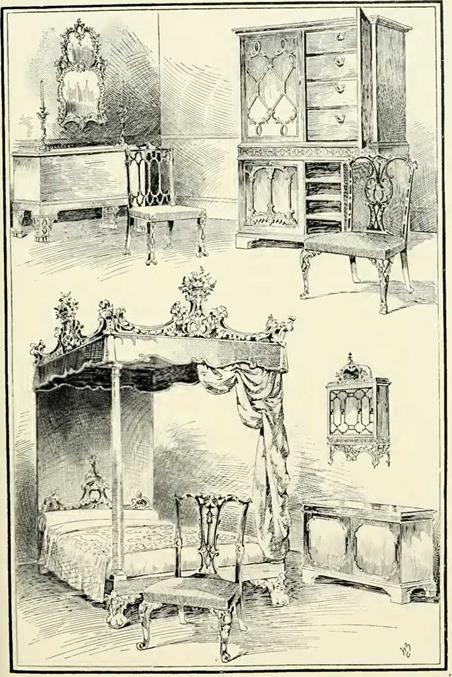

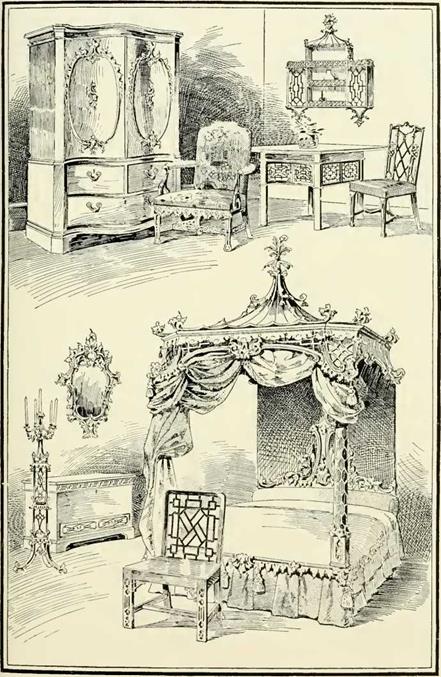

Passing on to our examples, and leaving out of our calculations interior architectural woodwork—joinery, wallpanelling, and the like—we shall see that the most complete object-lessons perhaps in “Elizabethan” carving and ornamental detail generally to be found are the stately and elaborate “four-post” bedsteads—“tester” beds—which have withstood the wear-and-tear of centuries, and bear testimony to the grandeur of the stately homes of England of the days when Drake was scouring the seas in pursuit of glory or booty; when Raleigh was revealing to his friends the mysteries of the pipe and the potato ; when Essex was composing his sonnets to his royal mistress; and the “ Immortal Bard ” was moving the people to laughter or to tears by the magic of his wondrous pen. With the bedstead, therefore, we will seriously commence our analytical and comparative study of this period.

Speaking of old furniture whose interest is supposed to be enhanced by some particular association, it is said that Charles Dickens, in a letter to a friend who was an ardent collector, stated, with mischievous glee, that he had discovered a veritable “ find,” in fact no less a treasure than a chair which “the Duke of Wellington had positively refused to sit in!” But, if we are to place credence in the histories that have accumulated round the sixteenth, and more particularly seventeenth-century bedsteads treasured in country houses throughout the kingdom, it would be difficult, if not almost impossible, to meet with a single one which Good Queen Bess had refused to sleep in! One and all appear to be honoured on account of the cherished and cumulative tradition

STYLE IN FURNITURE

![]() that they constituted, at one time or another, the resting-place of that sovereign’s precious and august form.

that they constituted, at one time or another, the resting-place of that sovereign’s precious and august form.

If all these traditions be accepted as true, we must come to the conclusion that this monarch cannot possibly have enjoyed many waking hours over and above those occupied by her travels from one mansion to another. Be that as it may—and the question of the authenticity of such stories does not concern us much—the genuineness of the date and design of the bedsteads is beyond dispute. It will be sufficient for our purpose if we study them carefully as types of style, and leave the verification of the traditions associated with them to others who may be more immediately interested in that question.

In our study and analysis of the ornamental detail of the “ Elizabethan,” we shall find, as a general rule, that the earlier the date of the piece we have to examine the more refined it will be in every particular. It will bear a closer relationship to the models set up by the Italian and French artists and craftsmen who were brought to this country by the liberality of Henry the Eighth, and by his ministers and court, who desired to enhance the material splendour of his regal surroundings—and of their own at the same time.

It will be remembered that I have pointed out how it was not at all uncommon for French and Italian painters, carvers, and other craftsmen of the highest renown, during the sixteenth century to be paid large sums in order to take up their abode in this country for a space, and work in the cathedrals, palaces, castles, and mansions of royalty and the nobility. Hence arose the English Renaissance, or “ Elizabethan,” as it is more generally styled ; and thus four distinct and most powerful influences were brought to bear in our midst.

First and foremost was that of the pure and unadulterated Italian Renaissance; then that of its French and equally beautiful offspring, the “ Frangois-Premier,” with which came the “ Henri-Deux”; and finally the Renaissance of the

Reference in Text

Page

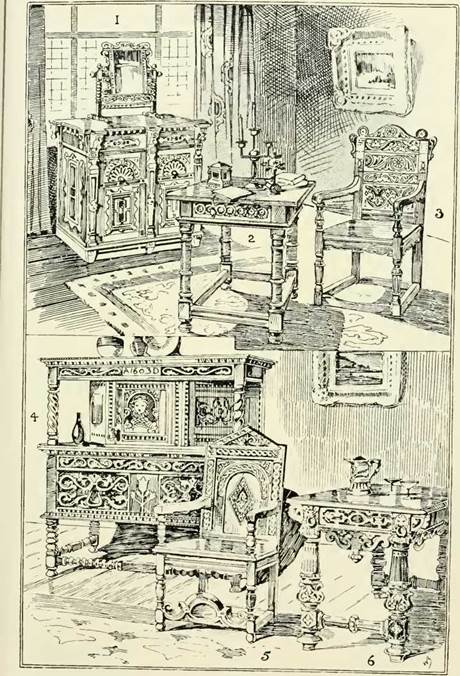

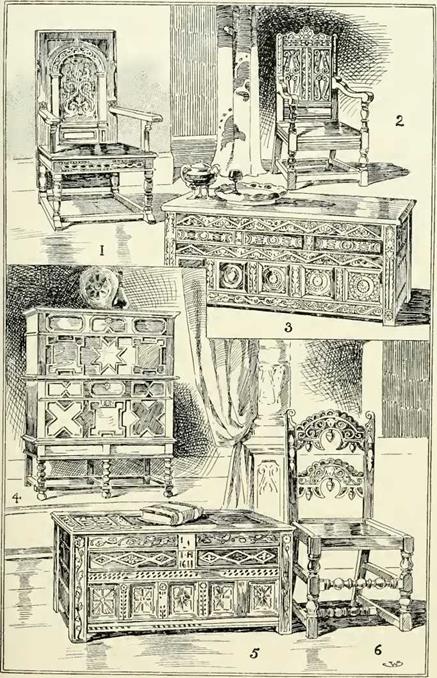

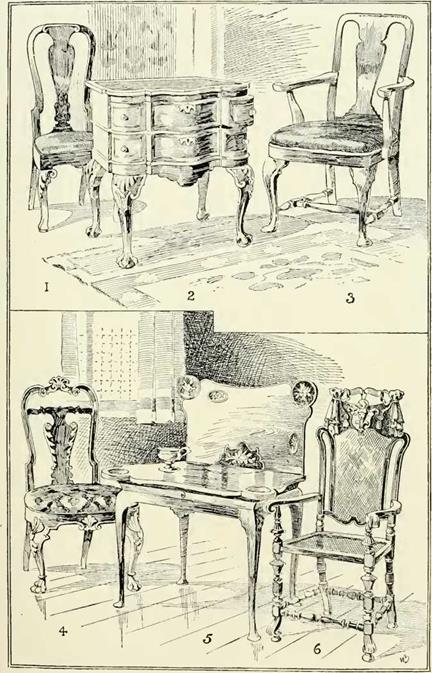

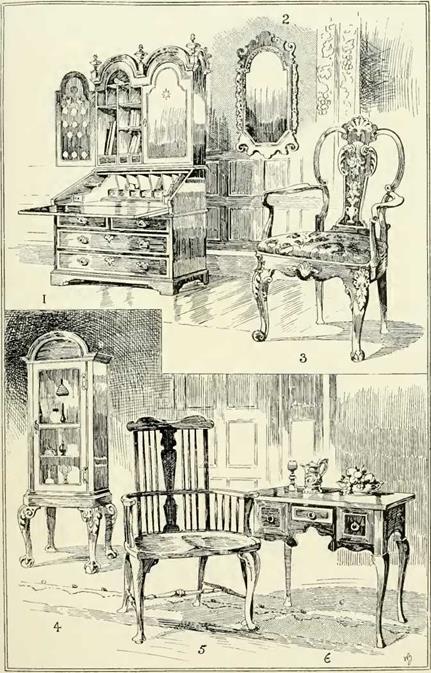

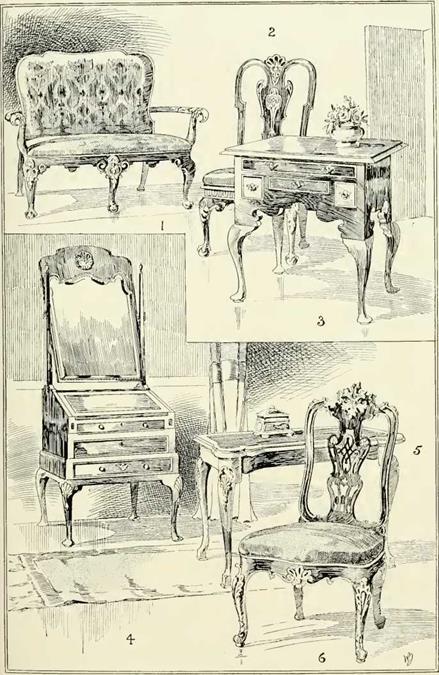

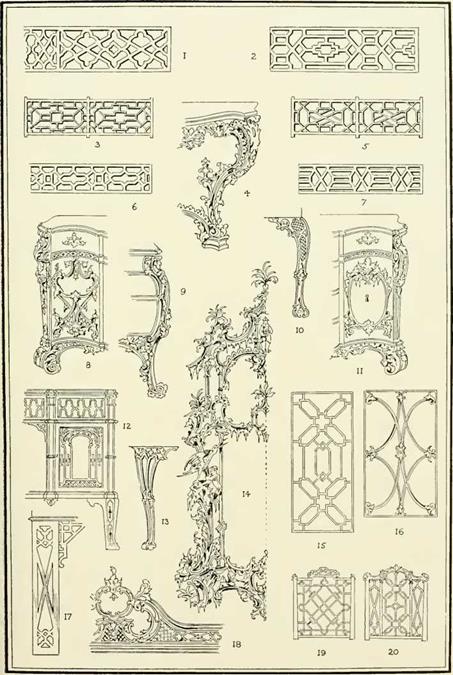

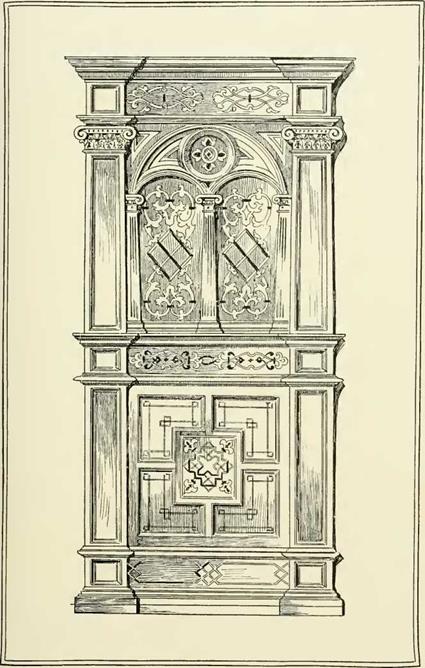

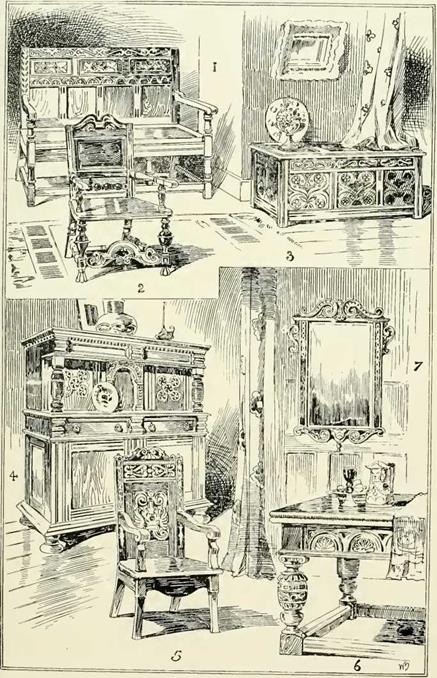

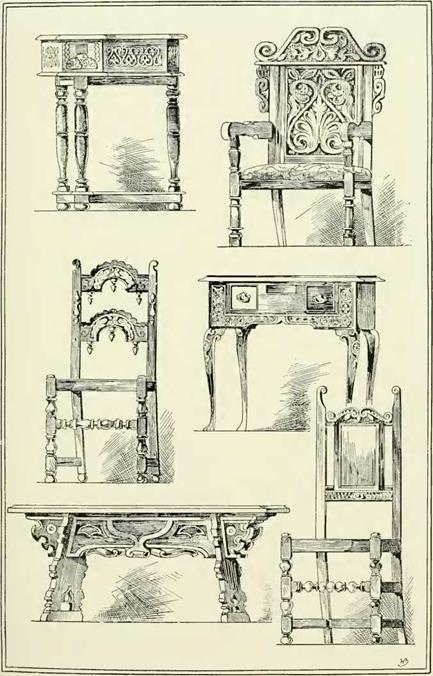

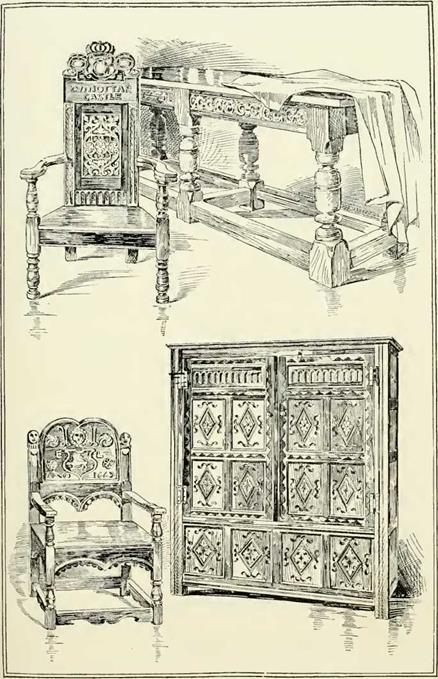

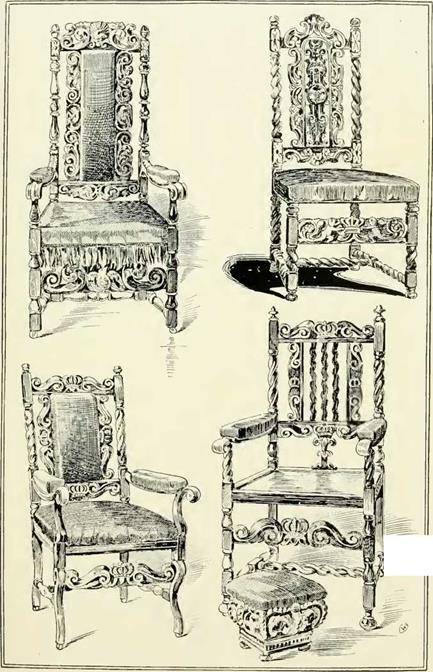

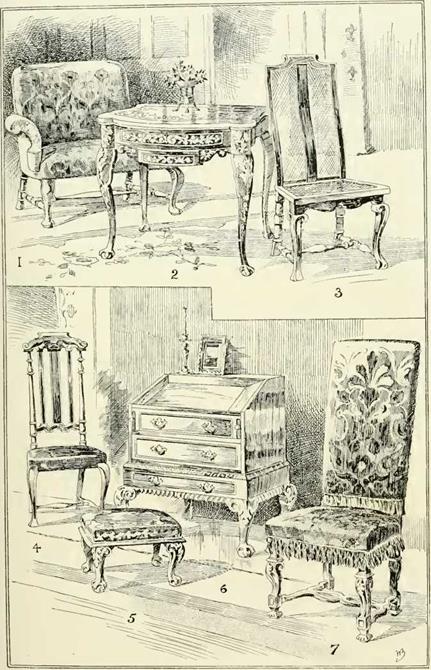

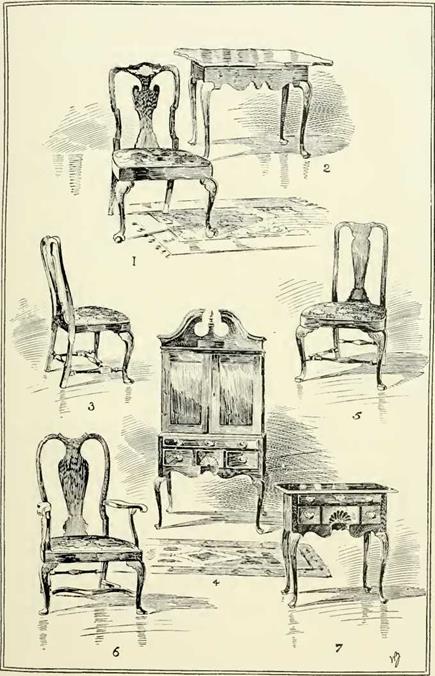

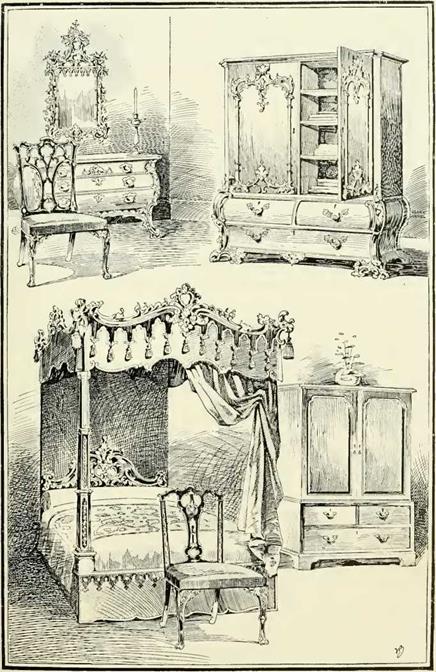

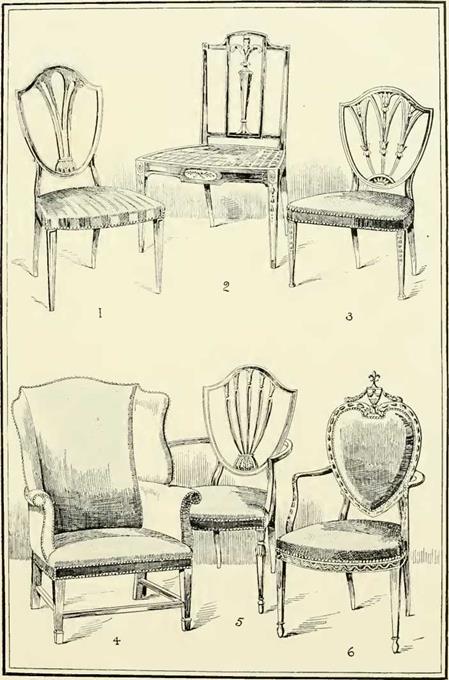

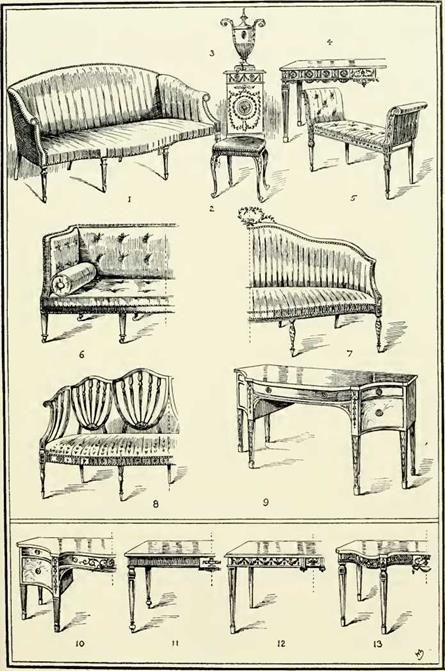

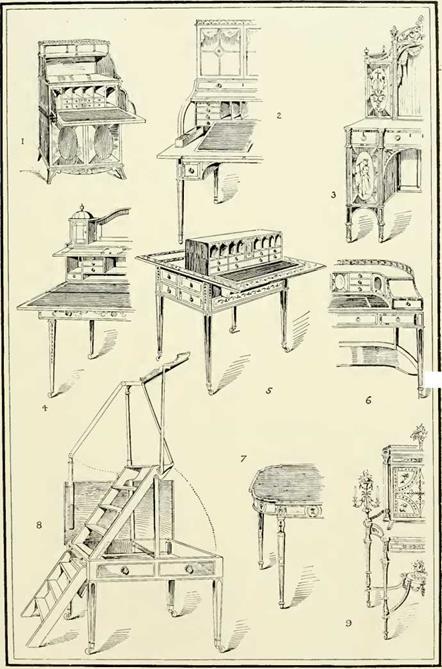

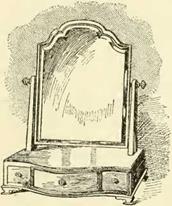

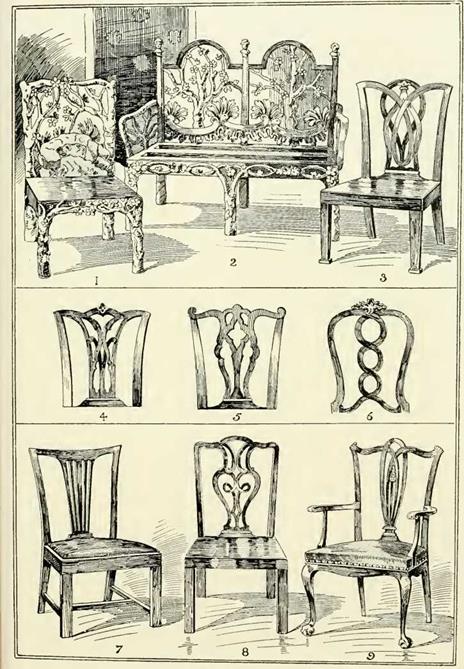

Fig. i. See 33. 54

.. 2. ,, 33, 46

,, 3. ,, 33, 43, 46

Page

Fig. 4. See 30. 32, 46

.. 5- .. 33. 54. 231

>1 6. ,, 27

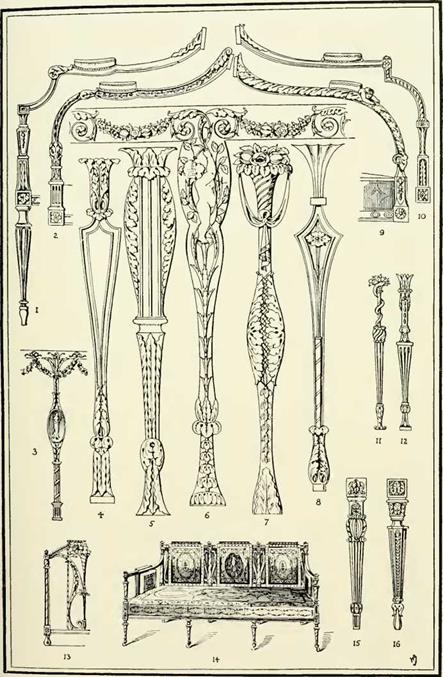

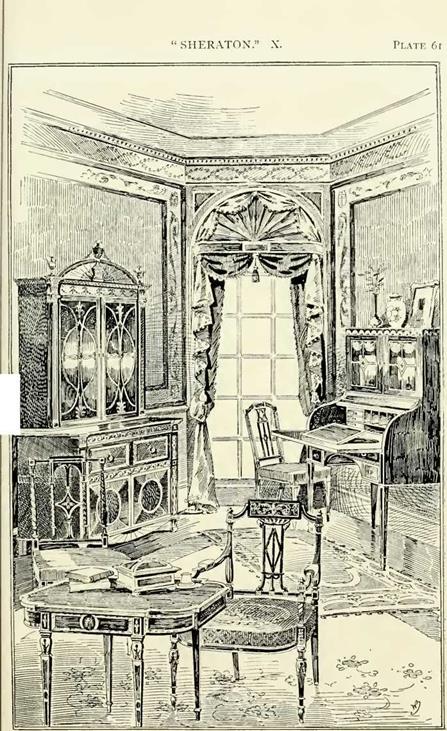

Netherlands, which played no inconsiderable part in supplying inspiration to the style whose name heads this chapter. That this inspiration was readily and freely drawn from all four sources by the English designer of those times, as well as of succeeding centuries, is amply demonstrated by the work of the period. We sometimes find, indeed, a curious, though by no means unpleasing, combination of the four styles in a single piece of furniture; in fact, this may be noticed to some extent in the bedstead which appears in Fig. 6, Plate I., in this chapter. Let us consider this carefully and in detail.

The manner of building-up the two pillars at the foot end is, of course, Italian in origin, but it is the Italian idea filtered, so to speak, through the “Francois-Premier" mind; while the “strap-work" enrichment of the upper part of the shaft partakes of both the “ Henri-Deux” and Flemish spirits. The generous proportions of the two rotund, bulbous members of the turning clearly bespeak the English taste of that day. It will be seen, then, that the complete scheme is a real melange of different styles; but it must be observed, at the same time, that all these styles, which spring from the same source, are in perfect accord, notwithstanding the many variations of detail to be noted.

What the quaint semblances of animals, glowering from the four corners of the canopy, or “tester," are intended to represent, I would not venture to suggest: they can hardly have symbolised the “ four angels,” whose safe guardianship has assured slumber to many generations for centuries past. All the rest of the carving of that section of the structure is, in conception and spirit, thoroughly Italian—the true Italian of the “Cinque-Cento.” In the four smaller carved panels in the upper part of the foot we have again “scraps ” of “ Henri-Deux,” which might have come straight from the wall-panelling of the beautiful ball-room in the Chateau at Fontainebleau ; but, in the carving beneath, the mark of the sixteenth-century

STYLE IN FURNITURE

![]() English carver appears most unmistakably. He had not yet been able to acquire the spirit of the styles which were even then comparatively new to France and Italy, the lands of their origin.

English carver appears most unmistakably. He had not yet been able to acquire the spirit of the styles which were even then comparatively new to France and Italy, the lands of their origin.

In this last carving we have the early beginnings of that type of panel in which more or less crude leafage of a nondescript character, outlined by an interlacing “strap," or plain “fillet" or edging of wood, is arranged geometrically— generally as a quatrefoil. In the course of our study we shall meet with this frequently. Finally, as regards this bedstead, the panelling at the head, in the semi-circular arches, is another medley of Italian and less pure “ Elizabethan."

I have fixed upon this truly magnificent old example for consideration at the outset on account of the fact that it would. be difficult to find another piece so exhaustively representative of every one of the essential factors of the style with which we are now dealing; it conveys, moreover, a remarkably adequate impression of the richness of the domestic belongings indulged in by the wealthier classes of this particular era.

So much space has been devoted to the discussion of this one piece, and to the endeavour to trace each individual item of detail to its proper source, that my remarks on other examples, dating from about the same period, and partaking in a greater or less degree of the same character, may be very materially curtailed. If the bedstead illustrated in Fig. i, Plate I., be studied in conjunction with that which we have been analysing, and a careful comparison be made of the various parts, detailed comment upon it may be dispensed with. Before passing, however, to articles of furniture in this style, but of another type, yet one more bedstead calls for notice, and that is the one portrayed in the interior represented on Plate IV. This is a study in sixteenth-century designing which many would describe as “ Early Eliza-

|

|

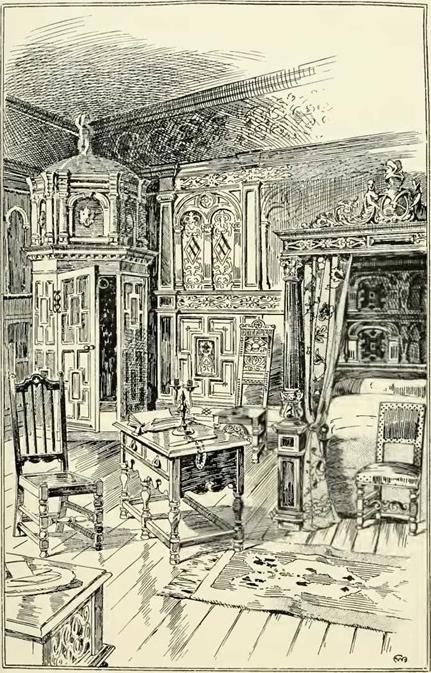

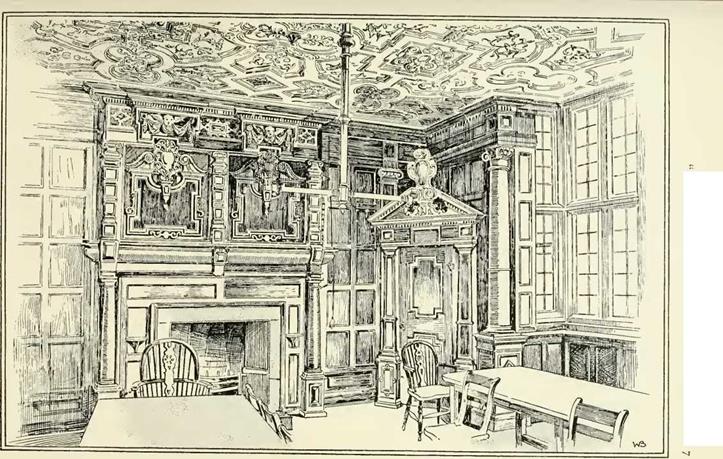

PANELLED ROOM, FORMERLY IN SIZERGH CASTLE, WESTMORELAND. NOW

IN THE VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, SOUTH KENSINGTON

Reference int Text. See pages 26, 33, 34, 54, 77

|

|

bethan"—which, as regards date, it really is ; but, so far as style is concerned, it would be far more correctly classified under the heading “ Italian," pure and simple. The detail in every part is just such as we find in the fifteenth and sixteenth century Italian work, unaffected by the foreign influences which came into play at a later period.

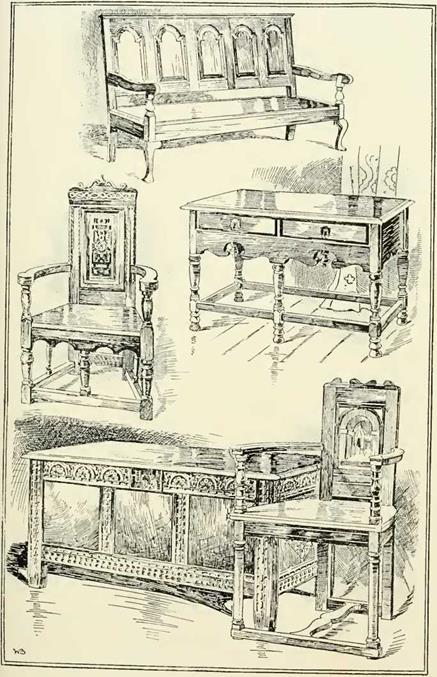

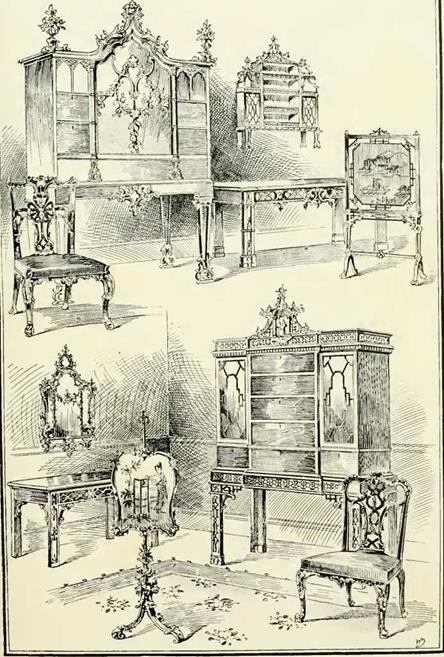

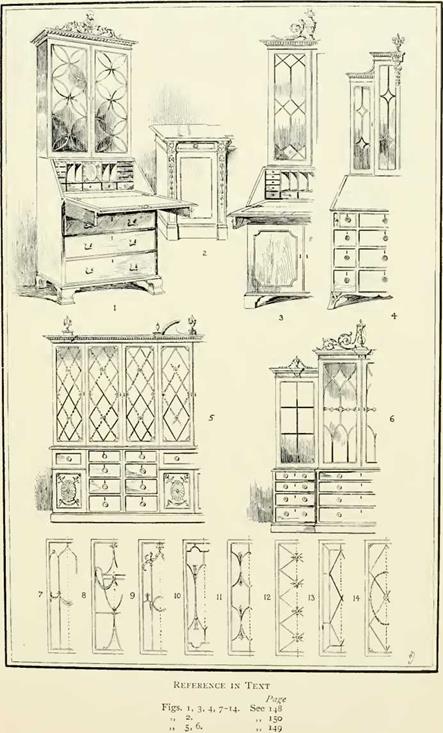

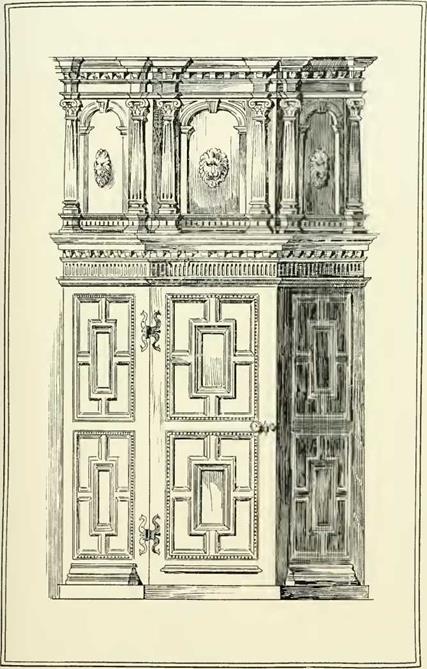

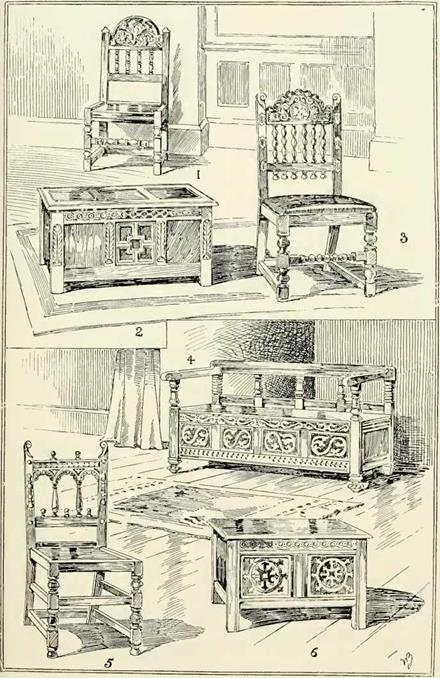

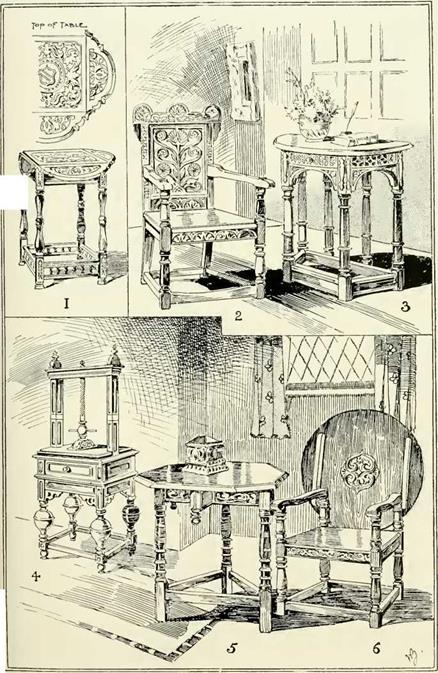

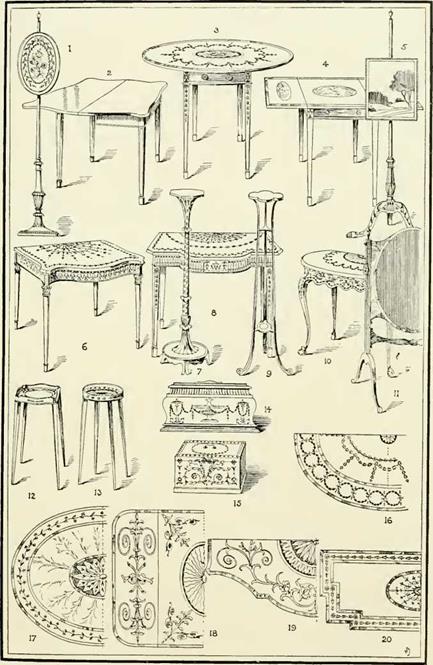

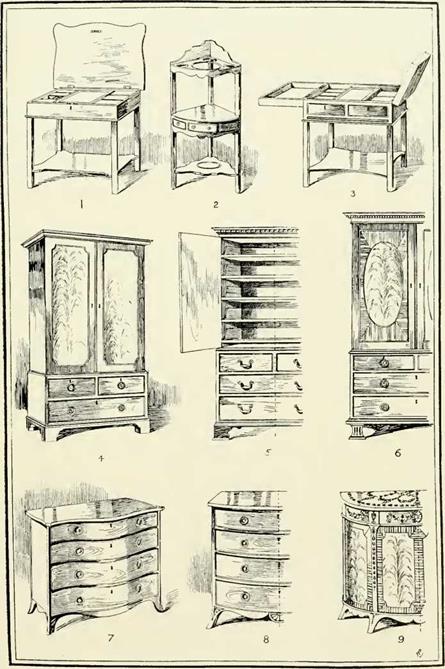

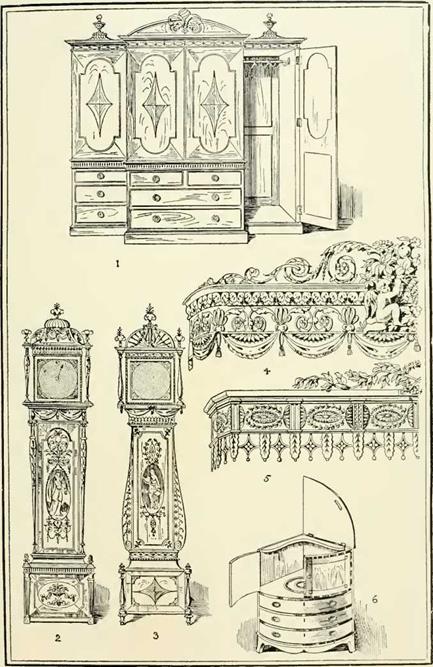

Of the date of the chest of drawers illustrated by Fig. 3, Plate I., I cannot speak with any degree of certainty, as I have not had the piece itself before me; neither can I vouch for the authenticity of the tables Fig. 6, Plate II., and Fig. 6, Plate III.; but in style they are as typical “Elizabethan" in every respect as we could possibly wish to find. In all three the “strap-work” element is pronounced, and this should be noted particularly, for it is a distinguishing feature, and one most particularly favoured by the English designers and craftsmen of this period. It is, indeed, rarely absent altogether from true “Elizabethan” creations.

I have suggested that this “strap-work," as found in the style under consideration, was largely inspired by the “ Henri-Deux,” but must again refer to the fact that the predominance of that class of enrichment in both the architecture and the woodwork of the Flemish and Dutch Renaissance must also be accounted responsible in a very large measure for its extensive employment in this country. There were other details as well introduced from the Netherlands which must be borne in mind ; but fuller reference to them will be made presently.

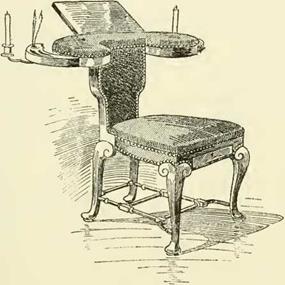

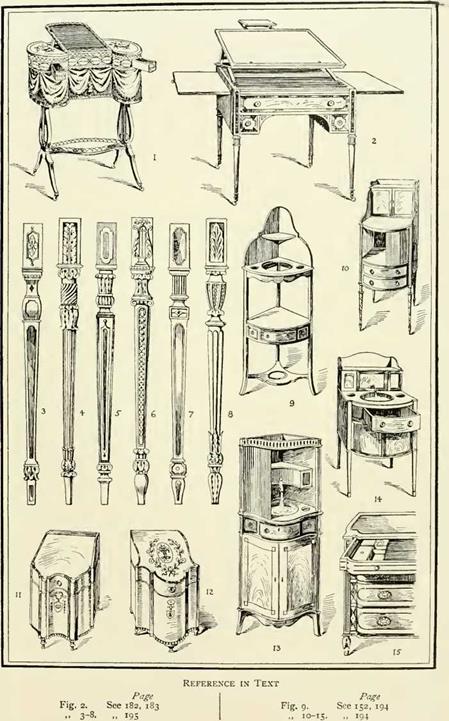

The old cabinet makers of the Elizabethan era did not devote any very great amount of attention to the design or manufacture of articles of furniture specially intended for the comfort of the literarily inclined, but the primitive desk form—the simple box with a sloping lid—was well known to, and produced by, them, though examples are extremely rare. Sometimes it was elevated to a convenient height for writing purposes by being placed upon a table-like base or support,

such as we find in Fig. 4, Plate I., and was thus raised, in more ways than one, to a position of some importance in the furnishing of the home. I may here remind the reader that it was no uncommon thing during the sixteenth century, and even earlier, for other cabinet work of the smaller kind— boxes, chests, and the like—to be provided with independent supports from which the box or chest could be removed expeditiously and at will; and the intention of that arrangement is clear. When so supported, they constituted apparently stable, and not unimportant, additions to the furnishing of any room. But, in the days when such impedimenta as “Gladstone" bags and leather travelling trunks were unknown, these articles often accompanied their possessors from place to place; it was therefore essential that they should be more or less portable: hence the adoption of this form of construction. The upper part could be easily carried about—in earlier examples holes were bored through the sides or ends for ropes or cords to pass through—and the stand was left at home for the reception of its burden on its safe return.

Figure 4 is of this type, and is interesting if only on that account; but it is interesting also in that it really marks the first stage in the development of the simple desk from its original form into that eminently sensible and useful piece of furniture the bureau, which came into such general use at the end of the seventeenth century. In the earliest stages, the lid was hinged at the upper edge, as in the ordinary desk ; but it was not long before some inventive genius struck upon the idea of shifting the hinge to the lower edge, so that the inner side of the lid might be used as a writing surface, as in the bureaux of to-day.

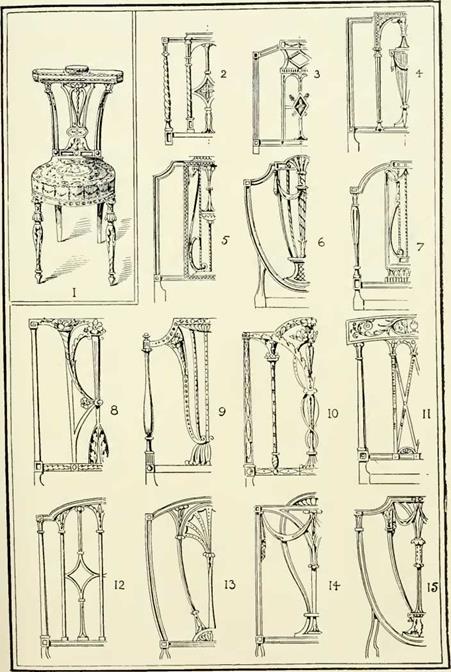

The consideration of the supports of this old desk reminds me that a few words on the subject of turning must be said here.

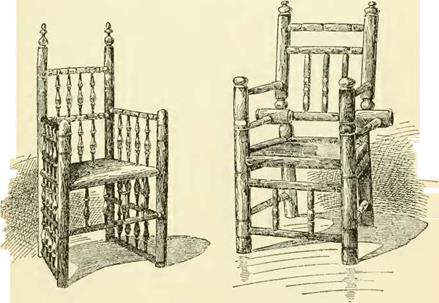

The lathe, it may be noted, was used very extensively in the production of much, if not of most, of the English six-

|

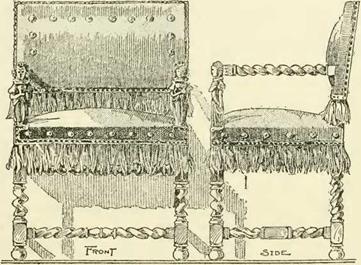

teenth-century furniture of the less expensive class. Take, for example, the three chairs that figure on this and the following page. The turning, however, was of a very simple, even primitive, character, revealing the presence of little or no fertility of ideas on the part of the designers and craftsmen who availed

|

Sixteenth-Century English Chairs (Composed principally of turned work) (See above for reference) |

themselves so generously of its aid. Instead of a pleasing variety of different “ members," such as is to be found in the turning of the best periods, delighting the eye by their graceful outline and ever-varying play of light and shade, we find the class of work illustrated in the sketches referred to. These pieces called for but limited skill to produce, and could therefore be turned out cheaply, which doubtless accounts

30

for their having been in such common use. With the steady growth of the “ Elizabethan," and with French and Italian models before him, the English turner, however, saw that he must attempt more ambitious flights ; how he succeeded in them we shall presently discover.

for their having been in such common use. With the steady growth of the “ Elizabethan," and with French and Italian models before him, the English turner, however, saw that he must attempt more ambitious flights ; how he succeeded in them we shall presently discover.

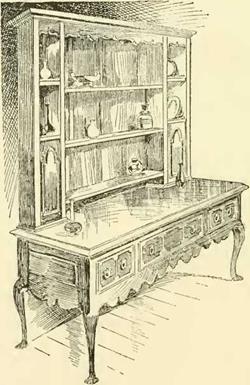

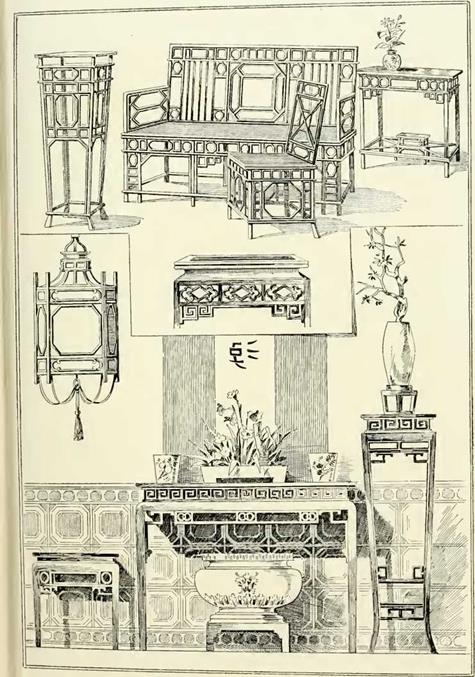

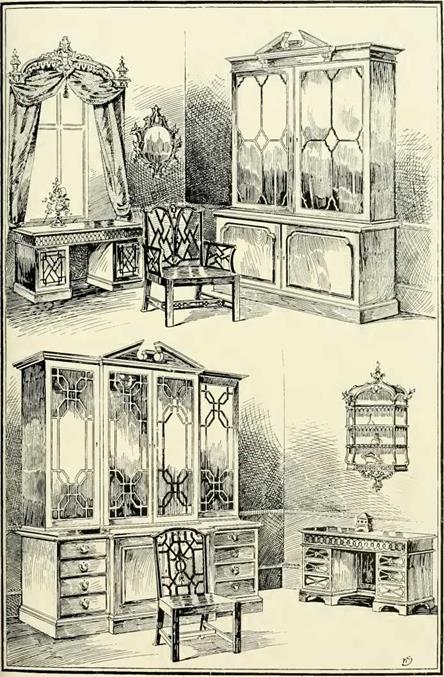

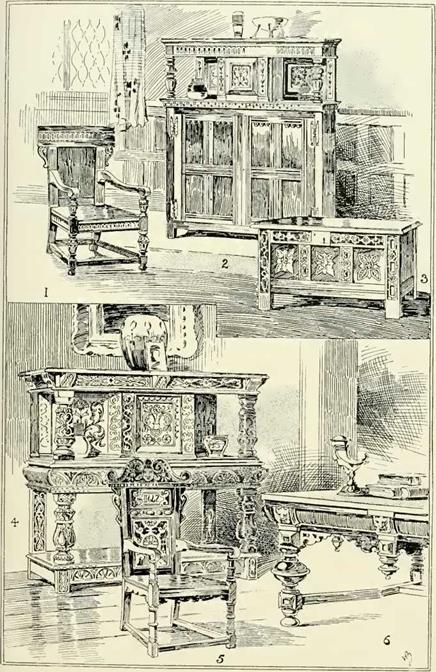

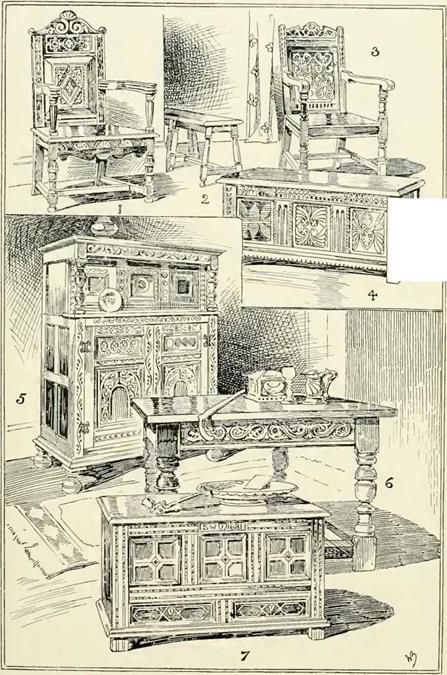

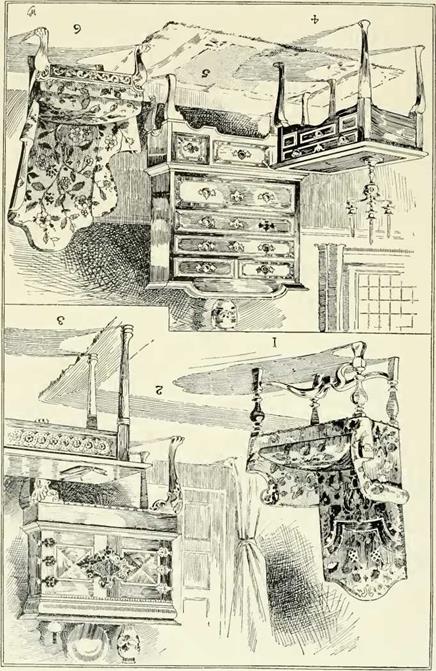

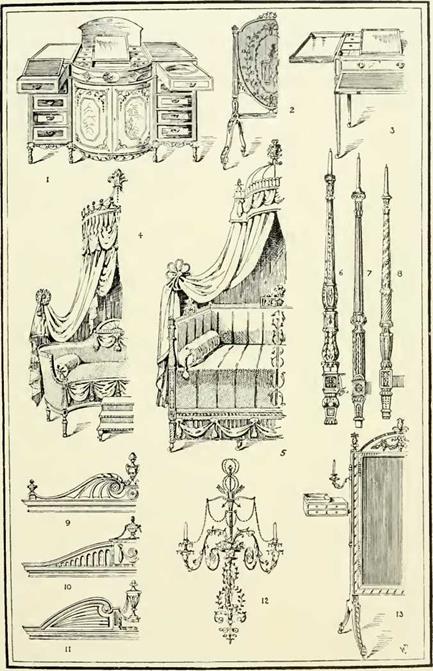

As we still pursue our investigation of the cabinet work of this period, the article that calls for our attention next is well worthy of more than passing notice, for it must really be regarded as one of the earliest progenitors of the modern sideboard, though its many descendants, in the course of centuries, passed through numerous changes and assumed many forms before they eventually became the sideboards of to-day. It is the “ Court Cupboard," then, that we will now discuss; and in Fig. 4, Plate II., and Fig. 4, Plate III., are represented two exceptionally fine old specimens of this particular piece of furniture.

As we still pursue our investigation of the cabinet work of this period, the article that calls for our attention next is well worthy of more than passing notice, for it must really be regarded as one of the earliest progenitors of the modern sideboard, though its many descendants, in the course of centuries, passed through numerous changes and assumed many forms before they eventually became the sideboards of to-day. It is the “ Court Cupboard," then, that we will now discuss; and in Fig. 4, Plate II., and Fig. 4, Plate III., are represented two exceptionally fine old specimens of this particular piece of furniture.

The “ Court Cupboard," both by its form and method of construction, clearly reveals its early origin. We can see at a glance that it was simply an elaboration of the ordinary, old

|

side-table, with a cupboard, or chest, placed upon it. The cabinet maker had evidently considered that primitive arrangement carefully, and, having gleaned his idea from it, proceeded to elaborate. The form of the cupboard was altered somewhat, and it was made a fixture; an ornamental canopy or top was added, and was supported at both ends by the introduction of turned, or square, columns; as a result, yet another piece of furniture, of a type not previously known, took its place in the Elizabethan home.

Both the examples illustrated, so far as I have been able to discover, are absolutely authentic in every particular. On the one that appears on Plate II., the date is carved to tell us the precise year of its manufacture ; but the presence of a date, however deeply cut and antique-looking, must certainly not be accepted without question as a sure guide. This feature has been all too often relied upon by unscrupulous imitators—to employ no stronger term—to serve as “corroborative detail calculated to give artistic verisimilitude to otherwise bald and unconvincing" shams. When, however, it is accompanied, as in the case in point, by certain other unmistakable indications of true age, its presence is heartily to be welcomed.

The cupboard under notice is, of course, of oak, as was all the best furniture of the period; and depends chiefly for its enrichment upon carving and turning, though the two side panels of the upper cupboard and the centre panel of the lower part provide a variation by the introduction of simple inlay. Upon the employment of inlay at the time of which I am writing, I shall have more to say presently.

The pattern in these two panels, and the border—a “ chequer ” design—above and below, are in ebony or bog oak, which stands out black against the lighter wood of the “ground," while the tulip-like form, with its attendant stems and leaves, in the centre panel of the lower part, is of holly, and is, consequently, lighter than the oak into which it is

STYLE IN FURNITURE

![]() sunk. The turning in this piece, I need hardly point out, shows that, at the time of its manufacture, a greater refinement and more variety in the shaping of members had come into play in this class of structural enrichment; and special note should be made of the spiral, or “twisted,” character of that in the upper part. When once introduced, spiral turning, as it is technically termed, came rapidly into vogue, and was for many years very extensively employed, and with excellent effect, particularly in the manufacture of chairs, as we shall see in the next chapter.

sunk. The turning in this piece, I need hardly point out, shows that, at the time of its manufacture, a greater refinement and more variety in the shaping of members had come into play in this class of structural enrichment; and special note should be made of the spiral, or “twisted,” character of that in the upper part. When once introduced, spiral turning, as it is technically termed, came rapidly into vogue, and was for many years very extensively employed, and with excellent effect, particularly in the manufacture of chairs, as we shall see in the next chapter.

Figure 4, Plate III., calls for no special comment further than that already offered, save that we may note, in passing, the presence of the “strap-work” in the upper turned pillars, and the superiority, regarded from the technical point of view, of the carving throughout. Both pieces, however, may be considered as belonging to approximately the same period.

To return to Plate I. for a moment : the chair sketched in Fig. 2, according to apparently well-authenticated report, once formed part of the worldly possessions of Shakespeare himself, and, so far as I am aware, no cryptogram has yet been discovered in the details of its design to upset that tradition. But, if we view the chair from above, the curve of the arms, taken in connection with the line of the front of the seat, will be seen to form most distinctly the half of a В! I present this important discovery most readily to the Baconian theorists. Can it be another link in the chain? Who shall say?

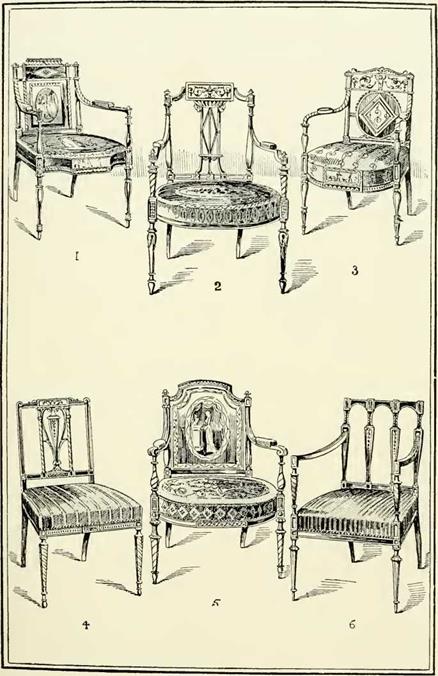

Reverting, with brevity, to the subject of turning as employed in the construction of chairs, the type illustrated on the opposite page is not infrequently found in the Elizabethan, and later, Jacobean mansions. But, more often than not, it was imported from abroad, and cannot be regarded as a home production. We sometimes see such chairs as these described as “ Elizabethan,” but their only claim to that description is to be found in the fact mentioned, viz. :—that they won a

certain amount of favour in this country during the reign of the sovereign after whom they are thus named. Even if some were actually made here, they were Italian, or Flemish, in form and detail nevertheless.

Figure 5, Plate I., I must deal with in my next chapter, as it belongs to a much later period ; so, indeed, do Fig. 5, Plate II.,

|

Chair of Italian Type (Not infrequently found in “ Elizabethan” and “Jacobean” Interiors) (See page 66 for reference) |

Figs, i, 2, 3, and 5, Plate III., and the tables and chairs on Plate IV. Some of these, notwithstanding that they are later as regards date than the types we have been studying, retain “ Elizabethan " characteristics, and, for that reason, they are not out of place here. This is specially the case with the massive arm-chair, Fig. 5, Plate III., with its “strap-work" carving in the back; and with the chair above, with its

tastefully enriched turning. Of these I shall say more by-

c

STYLE IN FURNITURE

![]() and-bye, and I will conclude my remarks on individual examples of the style with brief reference to the cupboard that appears in Fig. i, Plate II. In my opinion this is Flemish work; or, if not exactly from the Netherlands, it is a remarkably faithful copy of a Flemish original. The style of the panels, with their projecting “ lozenges ” in the centre; the semi-circular “ shells " in the arches above them, and the little turned knobs, “ drops,” or pendants so freely introduced, taken together with the “ building-up ” of the pilasters, tell at once of the country of their origin, and mark the design throughout as essentially Flemish. The example itself is only introduced here in order to show the closeness of the relationship which subsisted between the Renaissance of Flanders and that of our own land.

and-bye, and I will conclude my remarks on individual examples of the style with brief reference to the cupboard that appears in Fig. i, Plate II. In my opinion this is Flemish work; or, if not exactly from the Netherlands, it is a remarkably faithful copy of a Flemish original. The style of the panels, with their projecting “ lozenges ” in the centre; the semi-circular “ shells " in the arches above them, and the little turned knobs, “ drops,” or pendants so freely introduced, taken together with the “ building-up ” of the pilasters, tell at once of the country of their origin, and mark the design throughout as essentially Flemish. The example itself is only introduced here in order to show the closeness of the relationship which subsisted between the Renaissance of Flanders and that of our own land.

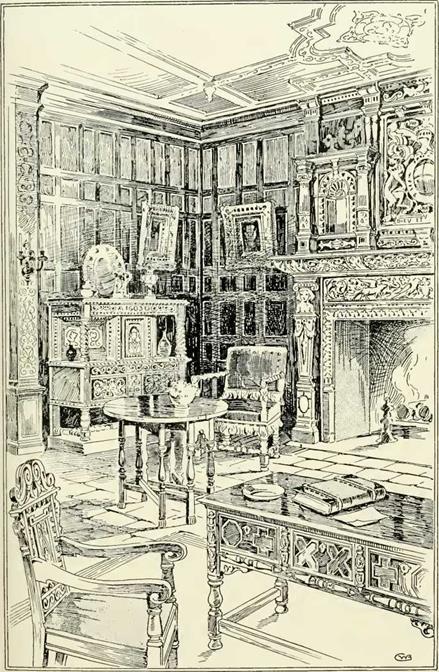

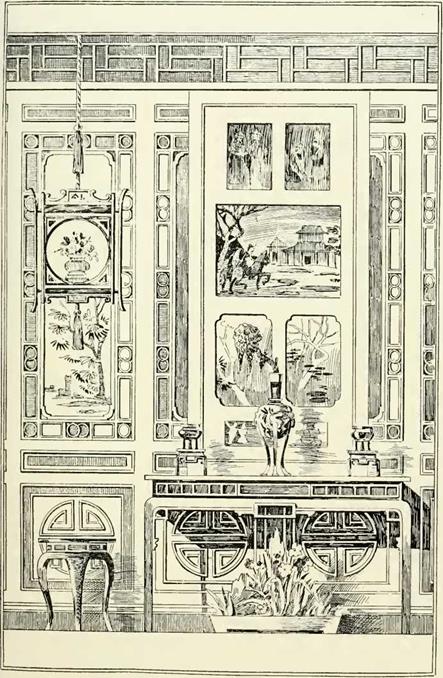

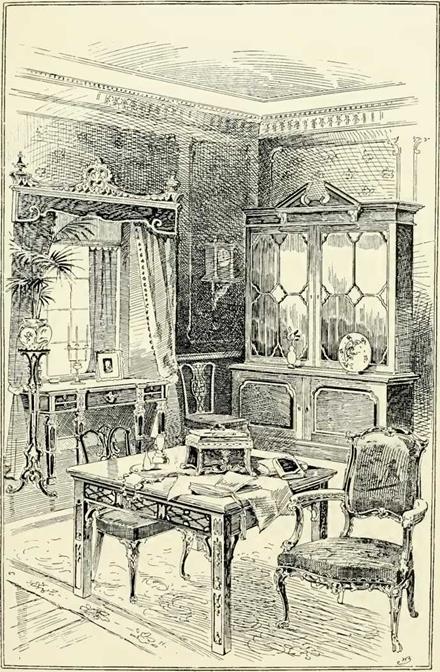

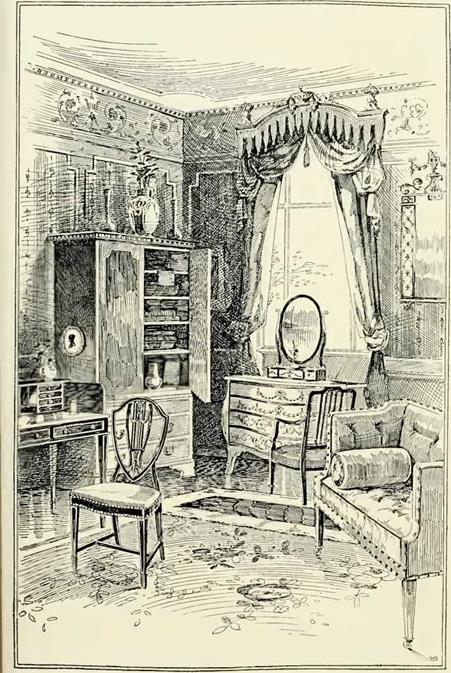

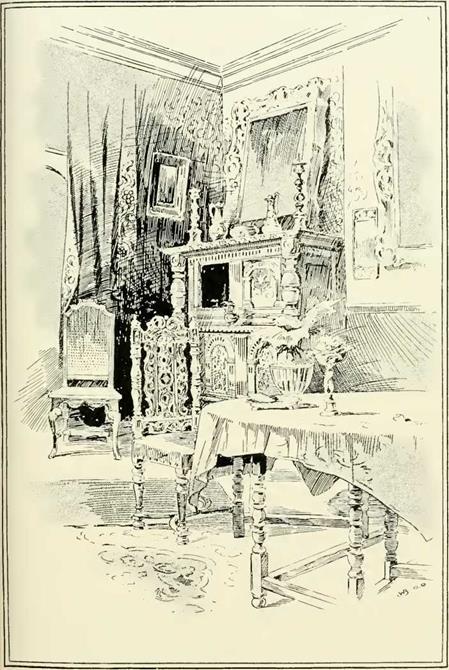

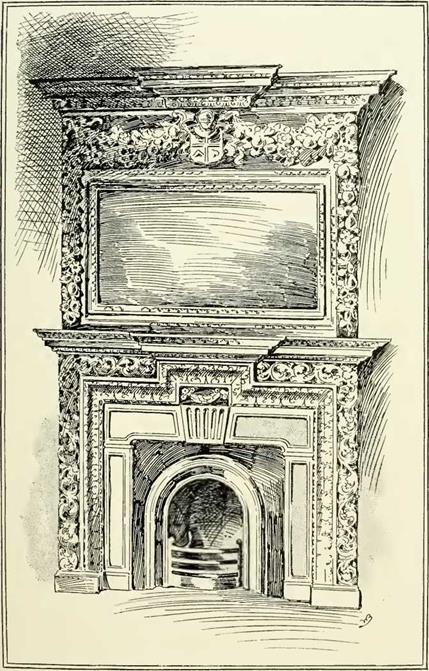

In bringing this chapter to a close, I shall invite my readers to study, for a brief space, a scheme of interior woodwork which will enable them to conjure up in their minds a more complete picture of the inside of the old Elizabethan mansion as it actually was than they could do through studying mere isolated examples of furniture.

The truly beautiful room of which a corner is limned on Plate IV. originally constituted one of the principal charms of Sizergh Hall, or Castle, in Westmorland. The whole of the joinery and panelling came into the market a few years ago, and was purchased for the nation by the Science and Art Department for the comparatively small sum of one thousand pounds. It was re-erected in one of the courts of the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington, where, fortunately for all lovers of fine old craftsmanship, it may now be studied at leisure, and its charms appreciated to the full. The authorities of the Department displayed the best judgment in making this acquisition, for the panelling in question is not only most interesting and valuable as an object-lesson in late sixteenth-century structural woodwork, but is also an exceptionally fine practical demonstration of the possibilities of pure “Elizabethan” marquetry, of which not any too

SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ROOM IN "YE OLDE REINE DEERE’’ HOTEL, BANBURY

Reference in Text. See page 35

much has been preserved. The panelling throughout, with the exception of the inlaid detail, is of oak ; and the general structural scheme, with its graceful pilasters, surmounted by Ionic capitals, and colonnade of arches within arches, is wholly Italian in character, Italian, moreover, of the best period of the “ Renaissance." In the long broad bands of the enrichment, which is in holly and bog oak, the effect is more than a little suggestive of the sgraffito, which was employed so extensively by the architects of the “ Quattro-Cento" and “ Cinque-Cento" for the external decoration of their buildings. The frieze of this room, in the old days, was, without doubt, of modelled plaster ; and it is more than likely that the ceiling was decorated by means of the same medium. Time has, of course, considerably darkened the tones of the woodwork; but, in its original state, with the black bog oak and almost white holly, standing out in contrast to the oaken “field," the effect must have been delicate and charming indeed, and very different from that of the sombre interiors usually associated with the period. The long panels with the diamondshaped centres have the “strap-work" feeling, but the detail is more free and less conventional in treatment than actual “strap-work" usually is. This panelling is of a character so exceptional that I have deemed it worthy of being presented to greater advantage than is possible in complete interior form, so on Plates V. and VI. it will be found drawn to a larger scale. The reader, therefore, will experience no difficulty in marking even the minutest characteristics, and will gain a truer conception of the beauties of the whole scheme. All the furniture in this room, apart from the bedstead, which has already been discussed, is of a period later than that to which the panelling belongs, and represents various phases of a style which we must consider in the next chapter. Another fine Elizabethan interior is illustrated on Plate VII. This may be seen in entirety to-day in “Ye Olde Reine Deere" Hotel, at Banbury. A cast of the ceiling is in the South Kensington Museum.

“JACOBEAN”

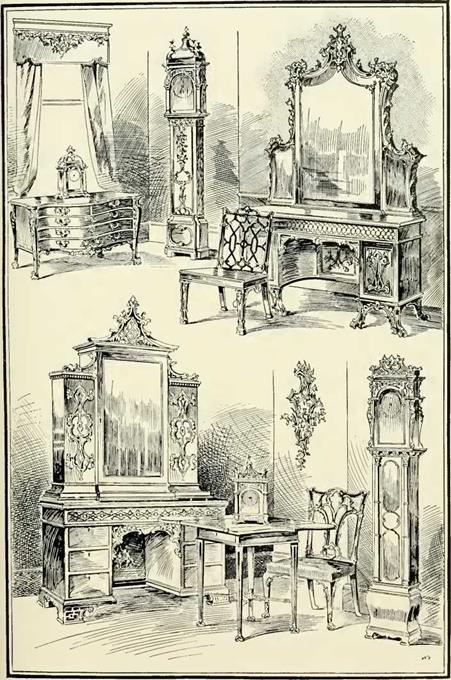

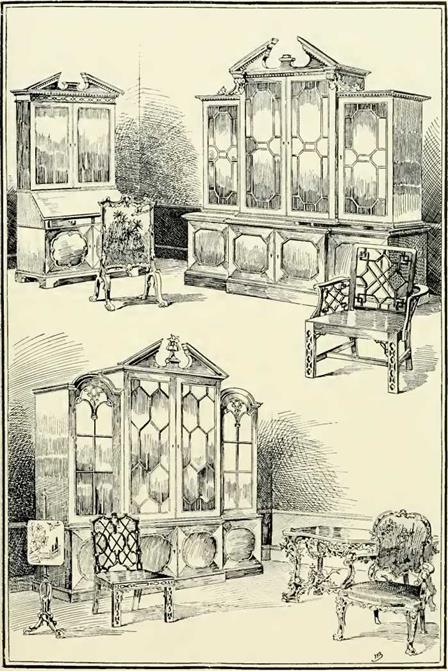

In studying, and attempting to arrange according to exact period, English furniture of times prior to the end of the seventeenth century, we have to encounter, and overcome as well as we can, difficulties that are not to be met with in the work of later times. In the century following, for example, and for the first time in the history of our craft, certain designers and manufacturers of cabinet work rose, by force of their own originality and genius, from the ranks of their fellow-artists and craftsmen, and became known and distinguished individually by name. They created distinct styles on lines selected by themselves, and those styles won the approval of the cultured public to so extraordinary an extent that nearly every other designer and maker of the time was content to copy them; indeed they became the order of the day, to the almost total exclusion of every other mode which was not in accord with them.

This being the case, and knowing as we do, almost to a year, the periods during which these notable men worked, the dates of the publication of their design books, and the names of many of their noble patrons, it is the simplest thing imaginable to classify their productions correctly, and place them in chronological rotation. All that we need trouble ourselves about with regard to them is to acquire a knowledge of the different characteristics by which one may be distinguished from another.

A century earlier we have no such assistance; there is no Chippendale, Heppelwhite, or Sheraton, to serve as a landmark ; the names of individual workers and creators of style were not then held in popular esteem, and, indeed, so

36

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

small was the notice taken of them that they were never placed on record. So, in the course of time, they have been lost to us for ever. It is interesting to note, moreover, that it was only during the second half of the eighteenth century

|

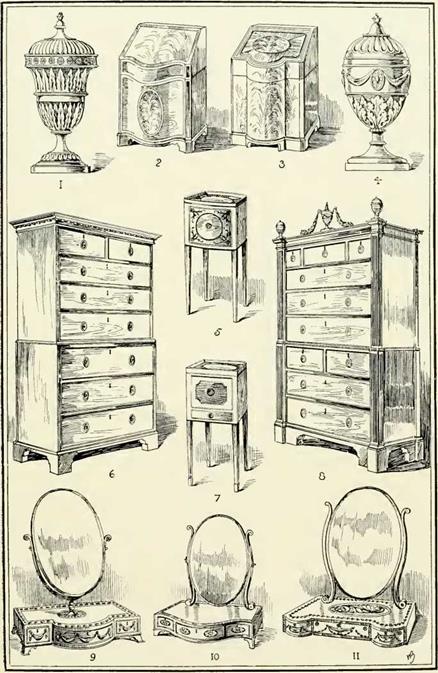

Seventeenth-Century Bedstead (Illustrating the employment of “Gothic,” “Elizabethan,” and “Jacobean” detail in one and the same article. Probably “restored,” or “made-up”) |

that leaders in this craft were distinguished from their fellows; for the desirable practice of giving them “a local habitation and a name," which soon fell into disrepute, disappeared altogether at the commencement of the century

з в STYLE IN FURNITURE

following — the nineteenth — and has never since been revived.

Even to-day we are aware, it is true, that our household gods were supplied by such-and-such a firm, whose title may possibly be known the world over ; but we are equally well aware that the individual, or individuals, whose title, or names, that particular firm bears, though they may be eminent politicians, winners of the Derby, men of letters, or perfect boon companions, are certainly not designers, nor even manufacturers, of furniture ; and the chances are that they could not draw a chair leg decently if they tried, much less design or make one. It is to these firms that the Chippendales, Heppehvhites, and Sheratons of our day look for a living, though not for fame, for they know full well that their names will be left carefully in the background — as securely hidden as possible. It must be noted that I am not now discussing the question whether the existence of such a state of things as that I have pictured be desirable or not, but am simply recording it, as showing how conditions change in the course of centuries. I may, however, mention in passing that a brave and determined attempt was made some years ago by a number of the disciples of William Morris to bring the artist and craftsmen to the front again ; to rescue them from the obscurity in which they have been overshadowed by purely commercial considerations for so long, and distinguish them from the mere “ middleman " or “ tradesman." The story of that attempt must be dealt with at some length in another chapter. Suffice it to say now, that “ the trade" was far too strong for these would-be reformers—the greater the pity. But of that more anon.

In our study of the “Jacobean," then, it is useless for us to look for names of individual artists or craftsmen ; and even if a few isolated examples could be brought to light, as doubtless some might by dint of much patient research in ancient archives, they would convey but little to our minds, and their

![]()

![]() Reference in Text

Reference in Text

. r<’gc

Tig. 4. See 40, 46, 48, 49, 52 " 5- ..44. 54. 231

.. 6. ,, 43, 64

.. 7• .. 44

discovery would prove of but small practical value in the pursuit of the inquiries we have in view.

Failing such aid, we must make it our aim to note the characteristics instead of the names of designers and craftsmen, and classify these as well as we can. It will be well for me to make clear here that, in the selection of examples by the examination of which I hope to convey a complete and correct impression of “Jacobean" furniture, I have been as careful as possible to confine myself to pieces actually made during the earlier part of the Stuart times—that is to say, during the period that elapsed between the years 1603 and 1688, a period which, I need not point out, includes the Commonwealth. What happened in the domain of furnishing under William and Mary and Anne, Stuarts though they were, does not come under the present heading, and must be considered quite separately. .

In my introductory comments upon early seventeenth – century English furniture, I have stated that, broadly speaking, the cabinet work of that age was characterised throughout by extreme simplicity of construction and severity of form, and it is now time for me to fulfil my promise to justify that remark by actual demonstration, which is easily done.

Even the ordinary casual observer, who knows as much about the technicalities of cabinet making as he does about differential calculus, will be able to see at a glance that, practically without exception, the whole of the cabinet work —that is to say, chests, cupboards, and the like—shown on the plates in this chapter, is, so far as construction is concerned, of so straightforward and elementary a type that it would present but small difficulty in execution even to the least experienced of professional cabinet makers. Indeed, there are not a few amateurs rejoicing in the possession of a bench and tools at home who might be trusted to accomplish creditably such simple tasks.

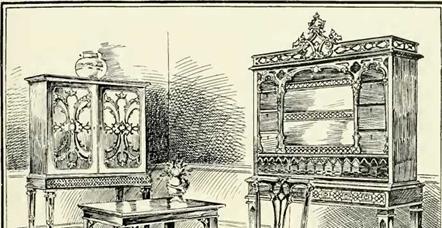

The most elaborate of all the pieces are the cupboard,

STYLE IN FURNITURE

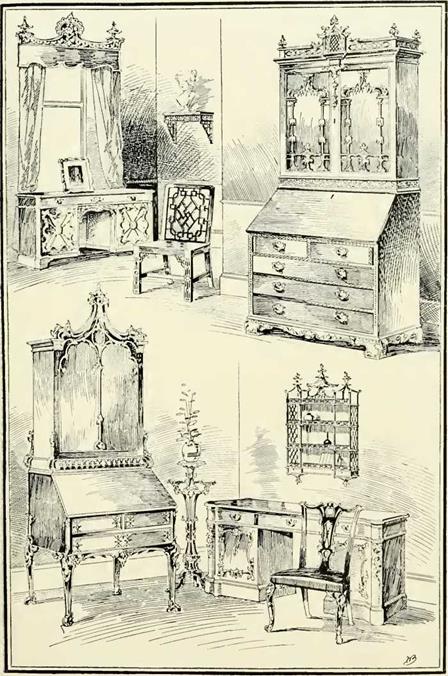

![]() cabinet, or press, Fig. 4, Plate I.; the " Bread-and-Cheese" cupboard, Fig. 4, Plate II. j and one or two other similar types ; and even they are free from all constructional difficulties, save such as are mastered in the А В C of the craft. It will be clear, then, that but very little study will enable anybody possessed of average intelligence to master quickly the general forms of the Jacobean " carcase." The next step is to acquire an equally complete knowledge of the ornamental detail, carved and inlaid, by the addition of which it was determined, in the old days, that those forms should be rendered pleasing to the eye. Here our task becomes somewhat more varied, and calls for more extensive study, though it cannot even then be regarded in any sense as difficult.

cabinet, or press, Fig. 4, Plate I.; the " Bread-and-Cheese" cupboard, Fig. 4, Plate II. j and one or two other similar types ; and even they are free from all constructional difficulties, save such as are mastered in the А В C of the craft. It will be clear, then, that but very little study will enable anybody possessed of average intelligence to master quickly the general forms of the Jacobean " carcase." The next step is to acquire an equally complete knowledge of the ornamental detail, carved and inlaid, by the addition of which it was determined, in the old days, that those forms should be rendered pleasing to the eye. Here our task becomes somewhat more varied, and calls for more extensive study, though it cannot even then be regarded in any sense as difficult.

The importance of the part played by the oaken chest in the sixteenth and seventeenth – century home has been so strongly insisted upon in my introductory review that, in considering which of these household gods to deal with first, we cannot do better than fix upon this honourable and honoured ancestor of so many modern articles. I have been exceptionally fortunate in securing a goodly variety for examination, so that every type that can be regarded as in any degree characteristic is represented in one or other illustration. Of these I may say at once that they are, without exception, made of oak, and that the enrichment is almost invariably carved, though it is, in rare instances, relieved by a touch of inlay here and there.

With regard to this carving, a word or two as to classification may be given at this stage. Much of it is of the description technically known as "flat”; that is to say flat surfaces predominate in the design, being thrown into relief by the spaces round and between them having been gouged-out, or "sunk,” by means of the gouge or chisel—as, for example, in the chest portrayed in Fig. 3, Plate I. Much more is of the "modelled” type of carving, as in the chest, Fig. 5, Plate I.; but none ever projects beyond the general surface of the

Reference in

Page

Fig. i. See 43, 44, 54, 55 ,. 2. ,,64

,, 3. „ 43, 44, 48

Text

Page

Fig. 4. See 42, 43

,, 5. ,, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 52

,, 6. „ 44, 64

,. 7. „ 49, 51, 52

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

article so decorated, or, rather, it is very rare indeed for it to do so. In order to keep to this rule, the carving, whenever employed in very high relief, was almost invariably sunk deep into the panels, so that even those details which stood out most prominently from the ground were still on, or below, the plane of the surface.

Over and above these two classes of carving, the chisel and gouge, more particularly the latter, were employed in yet another way, producing a result fairly effective, it is true, but one which the skilled manipulator of the tools will hardly dignify by the appellation “carving." The method adopted may be described as follows : The design to be executed, consisting usually of simple leaves and stems, was roughly sketched in upon the wood to be ornamented, and, that having been done, the lines of it were merely cut in, or incised, with a vigorous hand, so that, instead of standing out in relief, as in ordinary carving, they did just the reverse. This produced what is now styled “scratch carving"; and as it was very easy to execute, and cost but little, its employment was most extensive. It really belongs, in a measure, to the same school, technically speaking, as the monotonous “ chip carving " over which so many ladies at the present day spend time which might be much more profitably employed, and with such painfully feeble and uninteresting results. But the old work is far more vigorous and pleasing than its modern descendant.