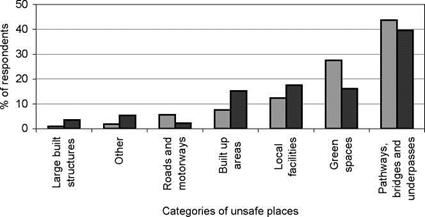

In the postal questionnaire the respondents were asked whether there were any places in their local area where they would feel unsafe alone, during the day time and after dark respectively. The data from these questions was converted in each case into a nominal (binary) variable where 1 was “yes” and 2 was “no” (denoting that there were, or were not, places in the local area where the respondent would feel unsafe alone). The respondents who had answered “yes” to either of these questions were then requested to identify up to three unsafe places in their local area, during the day time and after dark respectively. The respondents’ first named places were sorted into eight categories namely: “local facilities” (e. g. local shops), “roads and motorways”, “built-up areas” (whole districts that respondents identified as being unsafe, e. g. Oakwood), “large built structures”, “pathways, bridges and underpasses”, “ green spaces” and “other”.

The respondents from Birchwood were significantly more likely to feel unsafe in their local area, both during the day time and after dark, compared with the control group from outside (Table 3). Thirty seven per cent of the Birchwood respondents identified unsafe places in the local area during the day time, compared to 23% of the respondents from the control HCA’s. After dark, the contrast was more marked: 75% of the Birchwood respondents identified unsafe places, whereas only 54% of the control respondents did. The types of places most commonly identified as unsafe across the whole sample were “pathways, bridges and underpasses” and “green spaces” (Fig. 7).

Female respondents from Birchwood were significantly more likely to identify unsafe places compared to Birchwood’s male respondents (Table

4).

Women from Birchwood were significantly more likely to identify unsafe places in their local area, compared to their counterparts from outside (Table 5). It seems probable that Birchwood’s woodland setting contributes to this difference in perception.

|

□ Unsafe places during day time □ Unsafe places after dark Fig. 7. Respondents’ choice of unsafe places in their local area during the day time and after dark |

|

Table 3. Effect of living in or outside Birchwood on respondents’ tendency to identify unsafe places in their local area, during the day time and after dark

|

|

Table 4. Effect of gender on Birchwood respondents’ tendency to identify unsafe places in their local area, during the day time and after dark

|

|

Table 5. Effect of location in relation to Birchwood on female respondents’ tendency to identify unsafe places in their local area, during the day time and after dark

|

The findings therefore represent a curious paradox. As we have seen, whilst “green spaces” were often thought of as unsafe, they were also the most valued places in Birchwood, confirming that urban dwellers often hold conflicting feeling towards naturalistic or wilderness like places (Burgess et al. 1988). Whilst steps can be taken to make such places feel safer (Burgess 1995; Kaplan et al. 1998) they cannot be made to feel completely safe without removing the qualities that attract people to them in the first place. The existence of these contradictory feelings about naturelike green spaces strongly suggests that we need to re-examine existing models of landscape preference in which preference and safety are seen as co-dependent (e. g. Appleton 1975; Orians and Heerwagen 1992), and this is an interesting area for further research.