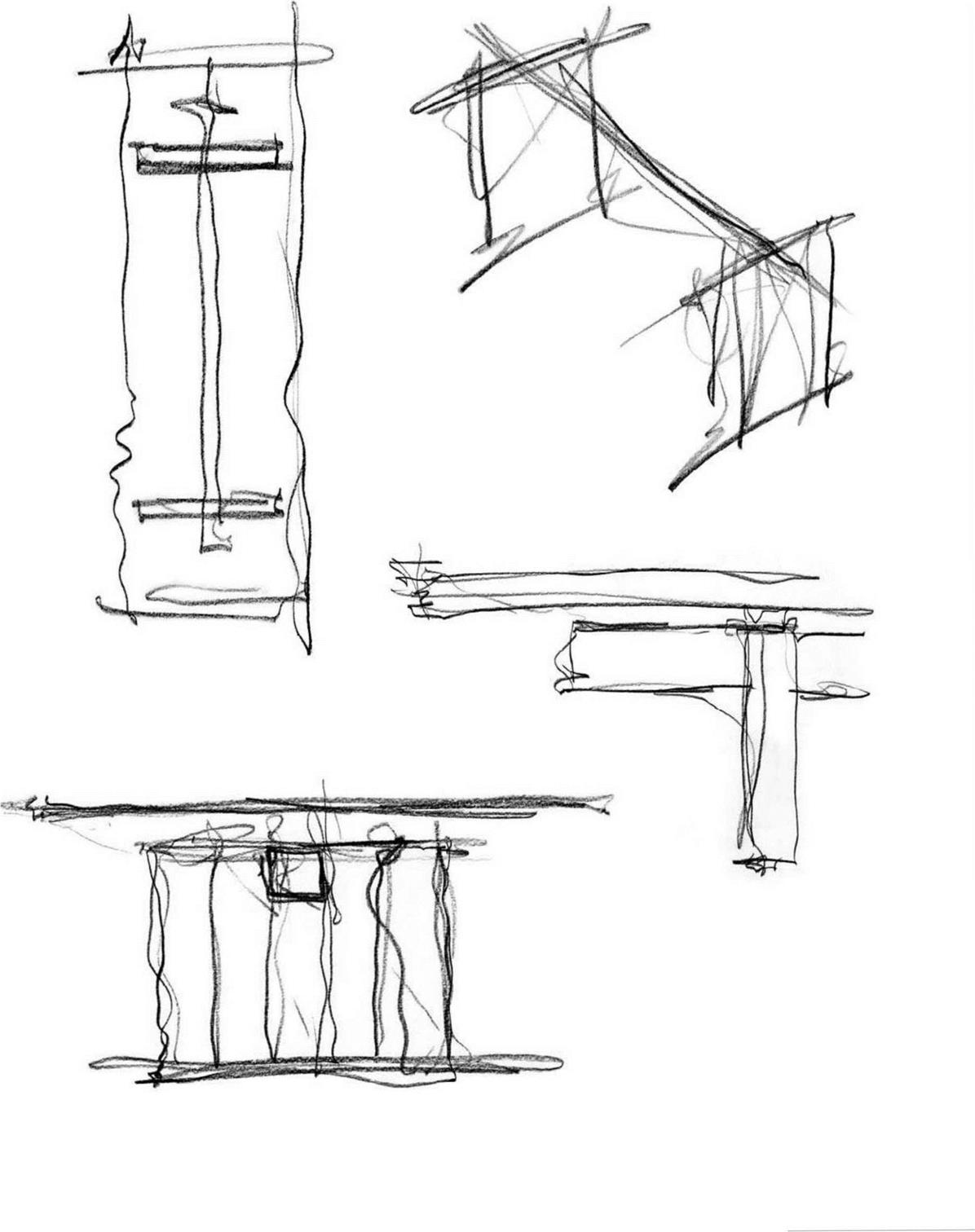

“Successful furniture is about connections, and how you bring materials together,” he says, “and I started to think about how to translate that structural language of instruments into furniture. It’s a bit of a structural experiment for furniture.”

“Successful furniture is about connections, and how you bring materials together,” he says, “and I started to think about how to translate that structural language of instruments into furniture. It’s a bit of a structural experiment for furniture.”

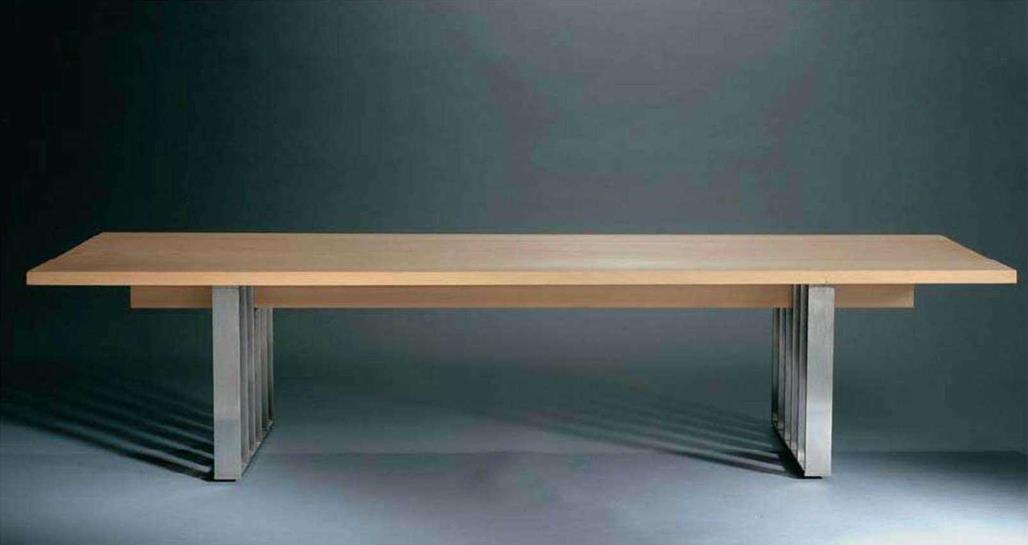

The Low Down Table’s apparent simplicity belies a hidden and unique feature: it can be tuned, much like a musical instrument. Jenkins points out that with most types of wood, a solid slab such as he’s used would warp and possibly crack over time and with changes in the atmosphere. While the Low Down is made from a solid plank of western or sugar pine, a wood that has a low moisture content, that helps it remain stable, it will expand and contract. But when it does, a few twists on special mechanical fasteners underneath the table let you readjust its shape, just as you might tighten or loosen the strings on a guitar. “This wood will move only minimally, and it will happen at the corners,” Jenkins explains. “Fasteners you can adjust are inserted in the underside and connected to the underlying frame, so you can tune it like an instrument. When summer comes around, and there’s lots of humidity, if you see the corners start to cup, you can adjust those with a few turns and it will bring the corners back down. It works through tension. There are two fasteners in the center and four at the ends. With this structure, you’re able to control it without overcontrolling it and forcing the wood to do what it doesn’t want to do.”

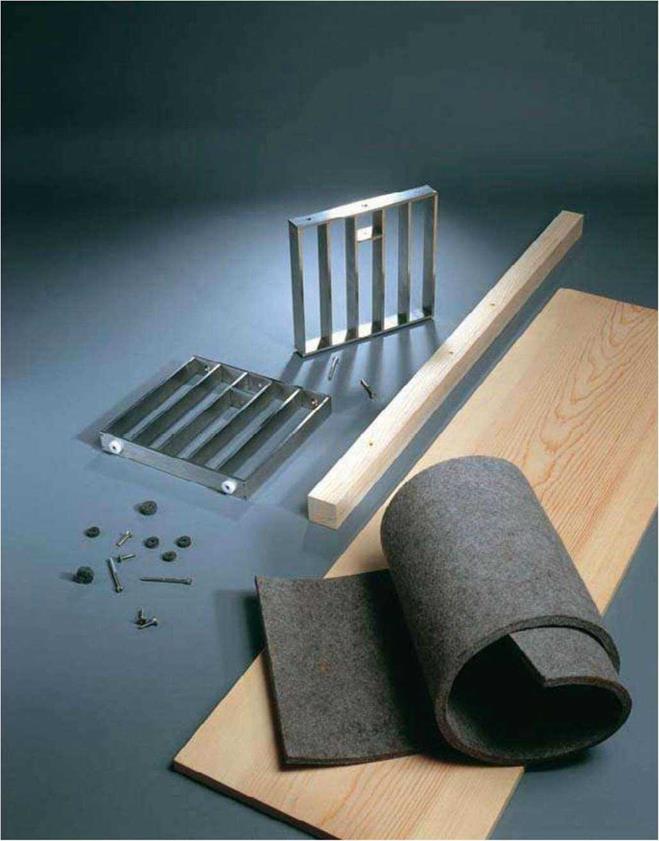

All this is achieved without altering the clean, uncluttered lines of the table itself. “What we’ve done is reduced the parts to essential elements,” says Jenkins. “It’s a plank, a beam, and space frames that elevate the beam off the floor.” However, even a table this lucid does have its manufacturing demands. “The biggest challenge is locating that pine in a consistent form,” says Jenkins. “You can’t just call up a supplier and say, ‘Send me X number of board feet of this western pine.’ You actually have to go to lumberyards and choose it. I try and use sustainable forestry resources and it’s becoming less and less available because so much of it has been consumed.”

The pine is finished with a beeswax linseed oil that is not harmful to the environment and won’t build up a hard, lacquered surface. Because the wood is fairly soft, and because he simply likes the material itself, Jenkins has added a pad of gray felt to the top of the table. “This is a material you wouldn’t typically see

|

|

|

|

і – -1

І и

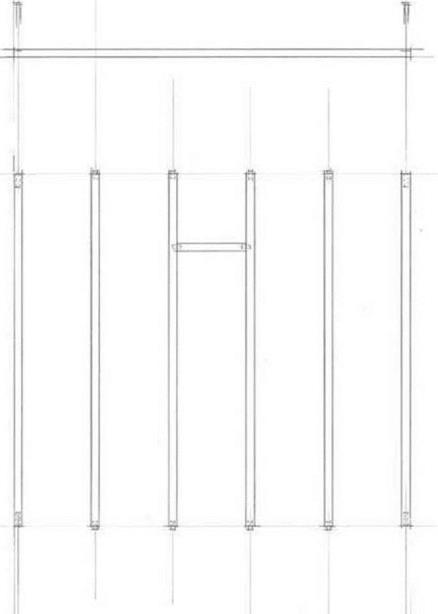

This exploded elevation of the leg frame assembly explains how the entire frame bolts in compression on just four corners. The rest of the connections are press-fit pins. Once the four corners are tightened, the frame becomes very rigid. Credit: Jeffrey Jenkins

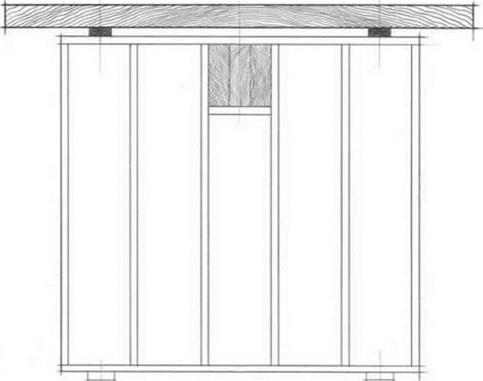

© A drawing of the side elevation shows how the frame connects to the wood beam and the top plank. Credit: Jeffrey Jenkins

|

|

exposed,” he notes, “because it’s an industrial-grade felt. It’s normally used for cutting out die-cut gaskets and washers for machinery. You also have the option of rolling it up and not using it and just enjoying the wood surface. The gray felt offers a nice visual contrast to this soft yellow, buttery pine. It’s a very natural color.”

The tabletop is supported by a beam made of the same pine. “But the beam has been glued in such a way that it won’t ever move,” Jenkins says. “It’s a lamination. The whole idea of the table is this central spine that’s holding it all together. We approached it as a structural problem. How do you take a solid plank of wood —it sounds so primitive and basic—and make this long table supported by a beautiful structure?”

Part of this beautiful structure is achieved by the two, barred frames at either end. “The end pieces are a kind of visual contrast,” Jenkins notes. “You have these thin, flat pieces contrasting with this big, solid timber of the spine and flat plank. I was also trying to create a formal geometry for the frame that was not material driven and reduce those flat pieces to be as thin as possible and still have a strong structure.” While the plank, beam, and felt pieces are always the same, the ends are offered in either stainless steel or padouk, an exotic wood with a rich red color.

Jenkins points out that in addition to being easy to assemble, disassemble, and tune up as the environment requires, the table has yet another benefit: “The other beautiful aspect of the end result is that it’s extremely lightweight,” he says. “It’s under 15 pounds (7 kg), not including the felt. You can just pick it up and balance it vertically on your fingertip. Which was another important part of the structural problem. “How can I make it as lightweight as possible in these materials?”’

Jenkins adds, “This is a very low-tech idea.” Which was, after all, the point of the exercise. “So much of furniture is overdone,” he says. “The world is full of these overstylized pieces that use excessive amounts of materials. If you look at bad furniture design, it just makes your eyes sting. Sometimes, you have to take a step back and get back to basics in terms of material and form, and take a philosophical stance.” For Jenkins, this attitude is the essence of a modernist aesthetic. “I like to think of a quote by Paola Antonelli, curator of the Department of Architecture and Design for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. When she was asked ‘How do you define modern?’ she said, ‘Modern is not about certain shapes. It’s a certain attitude. Nothing is wasted intellectually.’ I always think about that because that’s what I’m striving for,” says Jenkins. “Defining modernism through this low – tech structure and combination of materials.”

© The Low Down is easy to assemble and disassemble. The beam fits through each supporting end and the sugar pine top is adhered to the frame and support beam in six places with special fasteners that allow the wood to be “tuned.” The felt top is added both to protect the pine and as a visual complement between the blond wood and shiny metal supports. Credit: Aldo Tutino

© The Low Down is easy to assemble and disassemble. The beam fits through each supporting end and the sugar pine top is adhered to the frame and support beam in six places with special fasteners that allow the wood to be “tuned.” The felt top is added both to protect the pine and as a visual complement between the blond wood and shiny metal supports. Credit: Aldo Tutino

@“What we’ve done is reduced the parts to essential elements,” says Jenkins. “It’s a plank, a beam, and space frames that elevate the beam off the floor.” Along with an ingenious tuning device that ensures the simplicity always rings true. Credit: Aldo Tutino